Let’s fix this mess

In 2012–13 a total of 50 444 people lodged applications for asylum under the offshore component of the Humanitarian Programme. The Labor government increased the intake to 20,000 and granted a total of 20 019 visas, of which 12 515 visas were granted under the offshore component and 7504 visas were granted under the onshore component.

Even though there are estimated to be over 40 million refugees worldwide, when the Coalition formed government they reduced the humanitarian intake to 13,750.

As at 31 October 2013 there were 22,873 asylum seekers who had arrived by boat (including 1,811 children) who had been permitted to live in the community on Bridging Visas while waiting for their claims for protection to be processed.

The Coalition government* has now decided that anyone who arrived after 13 August 2012 will not be allowed to work so these people are now in limbo, facing uncertainty and financial distress.

[*Correction: As pointed out by Marilyn, this policy was introduced by Labor under Julia Gillard as part of their “No advantage” policy. Both major parties are complicit in this infamy.]

As at 31 October 2013 there were:

6,401 people in immigration detention facilities, and 3,290 people in community detention in Australia. This included 1,045 children in immigration detention facilities and 1,770 children in community detention.

Location: 4,072 people detained on the mainland (+ 3,290 in community detention) and 2,329 people detained on Christmas Island.

Length of detention in immigration detention facilities:

•2,432 people has been in detention for 0-3 months

•2,812 people had been in detention for 3-6 months

•864 people had been in detention for 6-12 months

•170 people had been in detention for 12-18 months

•23 people had been in detention for 18 months to 2 years

•100 people had been in detention for over 2 years.

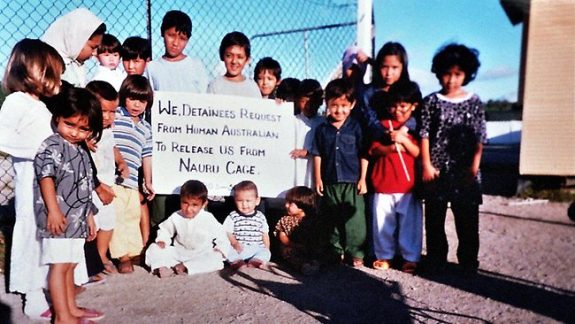

Due to Kevin Rudd’s “PNG solution”, anyone who arrived by boat after 19 July 2013 was transported to offshore detention camps. There are more than 1,700 asylum seekers being held in detention centres on Nauru and Manus Island with capacity for many more.

Since they reopened in 2012, only one application has been processed on Nauru and none from Manus Island.

In December 2013 the Coalition announced the removal of the 4000 Migration Programme places allocated to Illegal Maritime Arrival sponsored Family.

They also announced that they would not be renewing the Salvation Army’s contract to provide “emotional support, humanitarian assistance and general education and recreation programs” to asylum seekers in detention centres on Nauru and Manus Island beyond February. Immigration Minister Scott Morrison says the Government has been forced to make contract changes, because of the way the system was being administered by the former Labor government.

Several eyewitness accounts of the recent riots on Manus Island suggest they happened because the government refused to listen to questions from refugee representatives about their future and the conditions at the camp. Instead they inflamed the situation by telling them “You’re never getting out of this camp, it’s indefinite detention”. The deadly clashes on Manus Island allegedly flared after asylum seekers realised the Australian government had been ‘lying to them’ about plans to resettle them, and some asylum seekers decided to protest.

‘G4S were aware of tensions on compounds and intelligence reports indicated potential unrest for the period 16-18 Feb. DIBP [Australian Government Department of Immigration and Border Protection ] were advised NOT to hold briefing and meeting with compound representatives [allegedly to advise them that they would not be resettled]. Despite several protests from centre managers on the day, the decision to hold said meeting was dictated from Canberra and was the catalyst for the violence.’

Reza Berati came to us seeking safe haven. He was murdered while under our care. Scores of his fellow asylum seekers have been grievously wounded, others have committed suicide, others are driven to self-harm, all under our care.

We have been told we must stop the boats to save people’s lives. One thousand deaths at sea is certainly a tragedy. The greater tragedy is that we ignore this cry for help and punish the people who are desperate enough to risk their lives seeking our protection.

I don’t presume to be the suppository of all wisdom but you have to admit guys, what you are doing is not working. Stopping the boats and locking people up does not help one single refugee but it costs us a fortune, threatens our relationship with our neighbours, and draws international condemnation.

When you remove hope you remove life so, in order to save the lives of the over 30,000 asylum seekers who are currently under our protection, I would like to offer the following observations and suggestions.

Department of Immigration figures project that in the year ending 31 March 2014, 63,700 people arrived in Australia with working holiday visas. A further 48,300 arrived on 457 visas. These are not citizens of our country and do not aspire to be. They are here to earn a buck and then go home.

Why can’t we give some of these 112,000 temporary visas to asylum seekers who have passed health and security checks while they are awaiting processing? Instead of paying for them to be incarcerated or on below-poverty welfare payments, why not let them work and pay taxes? Even if the jobs are not ideal, they have to be better than being locked up with nothing to do and no chance to become a productive member of our society. Children should be in school, not locked up on a Pacific Island wondering why their mother can’t stop crying, and if they will live in a tent forever.

We do not have to increase total immigration to do this. We could give all the asylum seekers temporary working visas and still have over 80,000 available. More should also be done to see if Australian citizens could fill these jobs even if they are temporary in nature.

Instead of making our unemployed, disabled and single parents work in our Green Army, offer that work to asylum seekers or working holiday makers, and give our unemployed the opportunity to apply for the jobs in hospitality, agriculture and services that backpackers often fill.

Instead of importing labour on 457 visas, see if asylum seekers and our unemployed have the necessary skills to fill the positions. Train people where there are skills shortages. Only issue 457 visas where we truly cannot find anyone with the necessary skills.

In the last year we issued 101,300 permanent visas but only 16,500 of these were on humanitarian grounds and this number is predicted to fall to 11,000.

Increase the humanitarian intake from 13,750 to at least 30,000. Send representatives to all transit countries to start taking applications and begin processing them. They must give applicants a realistic time frame for processing and resettlement options.

Increase foreign aid and participate in condemning, and sanctions against, human rights abuses around the world.

Let’s fix this mess.