Castle Hill: The Irish Rebellion in Australia

I have a confession: When it comes to history I am a total nerd. Today I offer a nerdish contribution of an event that most Australians may not be aware of:

We are familiar with two rebellions in colonial Australia; the Rum Rebellion (1808) and the Eureka Stockade (1854). But there was one more; the lesser known Castle Hill convict rebellion, which if successful, had the potential to change our history altogether*.

The Castle Hill Rebellion of 1804 stands as the “largest revolt in Australian history, and perhaps as the most dangerous to authority” (Grimshaw et al, 1994:47). However, it is to Ireland we turn to trace its origins. Thus I will open with a brief overview of Ireland’s struggles for civic and religious freedom, which culminated in the Irish Rebellion of 1798, where similarities later emerge at Castle Hill.

The transportation to Australia of large numbers of the Irish rebels was a concern for the authorities and the colony’s Protestant gentry: these convicts were Irish; they were rebels; they were Catholic; and they were anti-British. The pages of history provide us with some eccentric portrayals of this convict group – Marsden’s being notable – and some of these are included here for they are a good representation of the colony’s mood.

It is pertinent then that the mood of the Irishmen also be presented. Patrick O’Farrell (Aust/Irish historian) captures this and it is included while reviewing the aims of the rebellion.

I will endeavour to draw on the passion around the rebellion, for it was passion that drove it, and passion that attempted to prevent it and ultimately destroyed it. In essence, the moods of and preceding 1804 perhaps provide a better window to review the Castle Hill rebellion than most of the historical events themselves.

The Castle Hill rebellion has often been called the ‘Irish Rebellion’ owing to its strong Irish presence and leadership. It is worth then returning to Ireland to briefly review the struggles, events and significant outcomes of the preceding years which, in the Australian theatre, were to culminate at Castle Hill in 1804.

The history of Ireland was principally concerned with the struggle for Irish civic and religious freedom and for separation from Great Britain. The principles of the French Revolution found their most powerful expression in Ireland in the Society of United Irishmen, which organised the rebellion in 1798. To the cry of ‘death or freedom,’ (Connell and Irving, 1980:92) these Roman Catholic peasantry rose to their cause and, although insufficiently armed, made a brave fight. At one time Dublin was in danger, but the insurgents were defeated by the regular forces at Vinegar Hill. A French force of 1100 landed in Ireland but was too late to render effective assistance.

The British prime minister William Pitt thought that the legislative union of Great Britain and Ireland together with Roman Catholic emancipation was the only remedy for Roman Catholic rebellion and Protestant tyranny in Ireland. By a lavish use of money and distribution of patronage, he induced the Irish Parliament to pass the Act of Union, and on January 1, 1801, the union was formally proclaimed. Owing to the opposition of George III, however, Pitt was unable to make good his promise of emancipation for Roman Catholics.

The prospect of the seditious Irishmen of 1798 being transported to Australia created fears to the level of near hysteria among the Protestant gentry. Governor Hunter expressed these concerns:

“If so large a proportion of these lawless and turbulent people, the Irish convicts, are sent into this country, it will scarcely be possible to maintain the order so highly essential to our well-being.” (O’Farrell, 1993:37).

Similar concerns were later echoed by Hunter’s successor, the ever-fearful Philip King, whose own assassination was plotted by Irish convicts in 1800. The Reverend Samuel Marsden, the Anglican chaplain in NSW, added the contention that:

“… if the Catholic religion was ever allowed to be celebrated by authority … the colony would be lost to the British Empire in less than a year.” (O’Farrell, 1993:39).

In 1800 and 1801, hundreds of these ‘dangerous’ Catholic Irish prisoners were transported to Australia for their part in the 1798 rebellion, with most of them being assigned to the Castle Hill government farm near Parramatta. This influx swelled the number of Irish prisoners in the colony to over one-third of the convict population. The United Irish Rebellion had given Australia what the authorities had feared: some anti-British manpower which, if united had the potential to bring the colony to its knees.

These rebels were a colonial cynosure: their fellow Irish hero-worshipped them; the authorities feared them and exaggerated their numbers and influence. Governors had a potentially rebellious role marked out for them: their vision of Ireland was of a country seething with violence, its populace maddened by discontents, plots, and popery, in the grip of secret societies with designs and power beyond measure. Given this nebulous landscape of fear, the actual number of Irish was irrelevant: all Irish were rebels. (O’Farrell, 1993:30-31).

That fine custodian of moral virtue, Samuel Marsden, who epitomised the Protestant gentry that the Castle Hill insurgents would ultimately rise against, was quick to make public his further concerns. He reasoned:

The number of Catholic convicts is very great in the settlement; and these in general composed of the lowest class of the Irish nation, who are the most wild, ignorant and savage race … men that have been familiar with robberies, murders and every horrid crime from their infancy … governed entirely by the impulse of passion and always alive to rebellion and mischief they are very dangerous members of society … they are extremely superstitious artful and treacherous … they have no true concern whatsoever for any religion nor fear of the supreme Being: but are fond of riot drunkenness and cabals; and was the Catholic religion tolerated they would assemble together from every quarter not so much from a desire of celebrating mass, as to recite the miseries and injustice of their punishment, the hardships they suffer, and to enflame [sic] one another’s minds with some wild scheme of revenge. (O’Farrell, 1993:39).

One of Marsden’s suggestions was to abolish Catholicism, thus surely making the convicts worthy citizens and providing them religious happiness and personal well-being, while the official doctrine considered that the severe and savage penal code was the ideal agency of moral reform. However, the Irish convicts refused to be “metamorphosed” (Kociumbas, 1992:61), and on the evening of March 4, 1804, three hundred of their numbers stirred the feared (and anticipated?) rebellion. Led by Philip Cunningham and William Johnston – Cunningham himself a veteran of the 1798 rebellion – they marched to the familiar cry of ‘death or freedom,’ to which they later added: “and a ship to take us home.” (O’Farrell, 1993:37).

Overpowering the officials at Castle Hill, the insurgents seized arms and ammunition before breaking off into four groups to scour nearby agricultural settlements to collect further arms and recruits. The groups scheduled to reconvene outside Parramatta. Meanwhile, colleagues inside Parramatta were to set fire to the farm of John Macarthur – another epitome of the Protestant gentry – and during the diversion this would create the rebels would take the whole settlement. A simple yet equally ambitious plan followed: escape down the river to Sydney and secure a ship to take them home.

Some historians believed that the French may have been poised – at this point – to play an active role in the rebellion. A strong French presence in the Pacific (itself a cause of paranoia among the colonials) was enough to suggest that their aid could be solicited. An option, in the event that a ship could not be secured and the rebels having the numbers to do so, was to hold the colony until the French arrived. It should be recalled that the French were willing to fight with the Irish Catholics in 1798, and it is speculated that the aforementioned 1800 plot to kill Governor King also envisaged seizing the HMAS Buffalo as an offer to Napoleon.

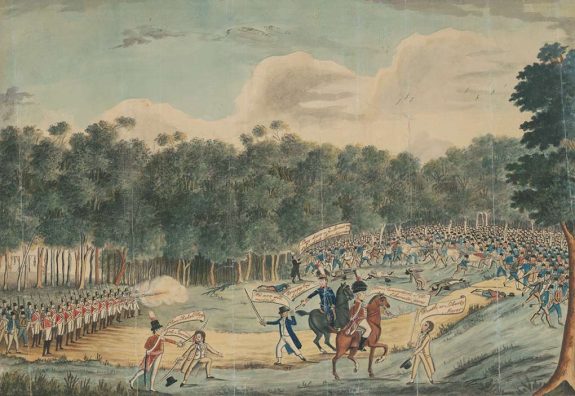

However, the 1804 uprising was to lose momentum when two of the four rebel groups failed to arrive at the planned rendezvous outside Parramatta. Although they numbered between 250-300, and they had collected extra muskets, swords and pistols, it was an insufficient force to attack the town. Worse too, their confederates in Parramatta failed to light the diversionary fires, leaving the town more heavily defended than anticipated. Turning their focus towards the Hawkesbury, matters were to worsen further when at dawn they were overtaken at nearby Vinegar Hill by the forewarned Major George Johnston, and fifty-six men of the New South Wales Corps who had marched from Sydney.

Contemporary records of the confrontation are favourably biased towards the military, and as such, Major Johnston’s ensuing acts are credited with reports of heroism, rather than with expressions of atrocity (personal opinion). However, it is from the contemporary records that we have at least gained some narrative.

Major Johnston called on the insurgents to down arms and submit themselves to the mercy of the proclamation (of martial law). The call was ignored, though he was able to persuade the leaders – Philip Cunningham and William Johnston – to meet with him and another trooper in truce. Dispelling the impropriety of their conduct, the rebel leaders ended the truce with shouts of ‘death or liberty.’ Under the virtue of discretionary power, Major Johnston responded with “great presence of mind and address” (Crowley, 1980:27) by presenting his pistol to Cunningham’s head and ordering his detachment forthwith to cut the insurgent body to pieces.

In fifteen minutes of zeal, against futile resistance, the troopers killed nine rebels (without loss) and left dozens wounded. Taking flight, three more were killed by the pursuing soldiers – a small number, considered Major Johnston – in view of the fondness for blood that his well equipped troopers exhibited. (Johnston was to later report that his own intervention prevented the cold-blooded murder of several unarmed prisoners.) During the next few days volunteer settlers pursued and rounded up the remaining rebels. Peace had been quickly restored, leaving the Castle Hill rebellion itself as only a very brief chapter in Australian history.

It was a telling victory for the authorities that was to extend beyond the affray: the punishments reserved for the rebel leaders was to act as a deterrent to future insurrections for the remaining sixty years of the convict system. The human cost was a chilling deterrent:

Phillip Cunningham was hanged without trial, there and then, in the middle of the Hawkesbury settlement for all to see. … Eight other leaders [were] summarily courtmartialled and executed, two of them hanged in chains. Nine others flogged (200-500 lashes), and thirty more shipped north to [the harsh] Coal River (Newcastle) settlement. (McLachlan, 1989:45-49).

Moreover, it was a victory for Protestant ascendancy and a measure of dealing with Catholic grievances. One such measure – quickly adopted by the authorities – was to geographically disperse potential rebels rather than congregate them in numbers, as they had, at Castle Hill.

The aims of the Castle Hill rebellion are not debated by most historians. The rebels – it is agreed – did not seek revenge nor did they kill anybody. Nor did they have any political objectives. It was in essence an uprising in response to servitude. The central aim was to escape death or liberty, and a ship to take them home. But O’Farrell questions whether there was anything to gain out of the motivation for – ‘Death or liberty’:

Death or liberty was a choice of their own contrivance. Some of them were seven-year men who could have worked out the remainder of their sentences. Cunningham was a skilled workman acting as an overseer of stonemasons; he had a house of his own; as had other leaders of the rising. They had something real to lose; why throw it – and life – away? Theirs was not the rebellion of crushed desperation, but of sentiment and hope, forlorn maybe; an affirmation of spirit … What drove the Irish was not only ideologies and dreams, but frustrations, sickness of heart, and impulses of affront: in a word, pride, which in the circumstances of convictism – not very different in style from the looser yoke permanently affixed by England to Ireland – expressed itself in grim determination not to be broken … The cruelties incidental to transportation, degradation, uprooting, and separation from families, might have weighed more heavily than the direct burden of forced labour. (O’Farrell, 1993:37-38).

The origins of the rebellion, I conclude, cannot be found in the harsh reality of the convict system, but in the heart of the Irishmen themselves.

*It is teasing to contemplate what might have happened if the rebellion was successful and the French had came to their aid. Would we still be speaking English?

References:

Connell, R.W; and Irving, T.H. (1980). Class structure in Australian history, Longman Cheshire, Melbourne.

Crowley, F. (1980). A documentary history of Australia volume 1: colonial Australia 1788-1840. Nelson, West Melbourne.

Grimshaw, P; Lake, M; McGrath, A; and Quartly, M. (1994). Creating a nation. McPhee Gribble/Penguin, Ringwood.

Kociumbas, J. (1992). The Oxford history of Australia volume 2: possessions 1770-1860. Oxford University Press, Melbourne.

McLachlan, N. (1989). Waiting for the revolution: a history of Australian nationalism. Penguin Books, Ringwood, Victoria.

O’Farrell, P. (1993). The Irish in Australia. Revised edition. New South Wales University Press, Kensington, NSW.

Rude, G. (1978). Protest and punishment. Oxford University Press, Great Britain.

Like what we do at The AIMN?

You’ll like it even more knowing that your donation will help us to keep up the good fight.

Chuck in a few bucks and see just how far it goes!

Your contribution to help with the running costs of this site will be gratefully accepted.

You can donate through PayPal or credit card via the button below, or donate via bank transfer: BSB: 062500; A/c no: 10495969

11 comments

Login here Register here-

Phil Pryor -

New England Cocky -

Michael Taylor -

Michael Taylor -

Andrew J. Smith -

Uta Hannemann -

Michael Taylor -

Canguro -

Terence Mills -

Michael Taylor -

Michael Taylor

Return to home pageWell Done. Is this from your (fast disappearing) youthful days? It was bitter, under reported, unclear and unfair in most ways. My own best memories of study are those doing Australian history to conclude a B A, and under Russell Ward at U N E. And I used to possess some of the Australian History magazines that came out, some in collected volumes. This is an essential study for the keen and thoughtful student of what happened and all those “whys”.

Naughty Michael, publishing such an interesting article that requires a response on such a busy morning.

Johnston had an interesting career in NSW. This suppression of the Irish Revolt of 1804, the settlement of northern Tasmania at the mouth of the Tamar River in 1806 at Georgetown, and the patsy for the Macarthur Rum Rebellion against Governor Bligh’s anti-rum campaign in 1808, for which he was cashiered.

However, the society of that time was very either one-eyed or ill-informed about Dr Darcy Wentworth, the former English highwayman who was offered a deal of re-locating to the Botany Bay colony or swinging at the cross roads until long after he was dead. Wentworth chose Botany Bay and so began the Wentworth family saga with him becoming the wealthiest man in the colony.

Some historians have said that a French naval vessel was on standby close to Sydney waiting for the signal from the rebels that they had taken Sydney. I have been unable to confirm this, however, there were French naval ships within the vicinity of NSW.

Phil, one of my spare rooms is stacked to the ceiling with history books or books on Aboriginal Australia.

I am, I’ve been told, eligible for membership of whatever the major historical society of Australia is. I’ve never bothered. In fact, I never even worked as a historian.

I ended up building databases and working in social security litigation and legislation. How boring.

Interesting, and to think that the descendants of the same and other Irish immigrants, and Jewish, are nowadays privileged to be honorary WASPs 🙂

“the 1804 uprising was to lose momentum when two of the four rebel groups failed to arrive at the planned rendezvous outside Parramatta.”

Why had they failed to arrive?

Uta, I’d have to go back to my books for an answer – a bit like the needle in a haystack. But from memory, I don’t recall the reason, or if one was ever offered.

It’s a pity, perhaps, or maybe not, that the historical record isn’t more informative. lack of detail around the particulars of the day’s events invite speculation; most of which is likely wildly wide of the mark, per accuracy.

Why did two of the rebel groups fail to arrive at Parramatta?

What time of the year was it? Seasonally hot, mild or cold? Did the good Irishmen need to stop for a cool-down in the midst of a hard slog? Did they have grog with them, for that matter, drink it, then fall into drunken slumber? Were they waylaid by some enticing wenches along the track, some rustic bordello offering discounts for quantity?

Or was the track a sodden mess after weeks of rain, with cloying mud that made the hike so difficult they just gave up?

Or were there second, third & fourth thoughts along the lines of ‘Jeezuz son of Mary, this ain’t worth it, I tell you’

Or like current standards, were the buses running late or the trains on strike?

It’s a pity. We’ll never know the answers.

Good and interesting research, Michael.

I have just been re-reading 1788 by Watkin Tench the British marine officer who described first hand First Fleet experiences and the early settlement at Sydney Cove : in particular the interactions with the local aboriginal people is quite revealing and shows the empathy and humanity of Arthur Phillip’, quite often overlooked in contemporary dialogue.

History can be fascinating, eh ?

Thank you, Terry.

The English were infatuated with the Aboriginal women (for obvious reasons). It might have been Tench who, upon seeing a canoe with you ladies near his ship, did the customary English thing and tossed them his handkerchief.

They paddled over to the kerchief, picked it up, studied it, and tossed it in the back of the canoe.

Taken back by this insult, Tench(?) rudely yelled out; “If that’s your attitude, madam, you can keep my kerchief.”

Canguro, it was early March, a particularly hot time of year to go on a long walk.