A belated ‘Recognition’ and a ‘new policy’ (Part 1)

Part Nine of a history of European occupation, rule, and brutal imperialism of Indigenous Australia, by Dr George Venturini.

A belated ‘Recognition’ and a ‘new policy’

On 11 October 2007, in one last opportunistic electoral manoeuvre, Prime Minister Howard announced his support for “The eight time: Constitutional Recognition for Indigenous Australians” in a new preamble to the Constitution. Howard decided to reverse the politics of racial division which had long served him well.

Just six weeks out from the election, he came out with a commitment to reconciliation with Indigenous People.

Here was the plan. “I announce that if I am re-elected, I will put to the Australian people within 18 months a referendum to formally recognise Indigenous Australians in our constitution – their history as the first inhabitants of our country, their unique heritage of language and culture, and their special, though not separate, place within a reconciled, indivisible nation,” he said.

Perhaps anticipating a sceptical response to his announcement, Howard adopted a humble tone, acknowledging his record included times “when dialogue between me as prime minister and many Indigenous leaders dwindled almost to the point of non-existence.”

“I fully accept my share of the blame for that,” he confessed. “This is the first time there’s been a rigorous process to actually find out what Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples want.”

John Winston Howard was the man who ran the long scare campaign against land rights, who decried the “black armband view” of Australian history, who resisted calls to repudiate the naked racism of One Nation and who refused, in defiance of popular sentiment and massive public demonstrations including a 200,000-strong march across the Sydney Harbour Bridge, to say “sorry” to the Stolen Generations. Howard was the man whose government abolished the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Commission – which, despite its flaws, was a bold experiment in self-determination – and preferred the mainstreaming of services and old-fashioned paternalism.

But on 24 November 2007 Howard lost the election which brought to office the Kevin Rudd/Julia Gillard Labor government, formed on 3 December.

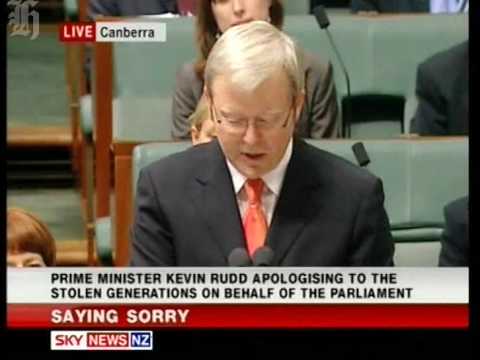

On 13 February 2008 Prime Minister Kevin Rudd delivered a comprehensive and moving apology for past wrongs and a call for bipartisan action to improve the lives of Australia’s Indigenous and Torres Strait Islanders.

“The Parliament is today here assembled to deal with this unfinished business of the nation, to remove a great stain from the nation’s soul, and in a true spirit of reconciliation to open a new chapter in the history of this great land, Australia.” Rudd told Parliament.

This was “Government business, motion No. 1,” the first act of Rudd’s Labor government and it was coming after the 11-year administration of Howard specious and persistent refusals to apologise for the criminal acts of previous governments.

Rudd’s Apology was particularly addressed to the so-called Stolen Generations, the tens of thousands of Indigenous children who were removed, sometimes forcibly, from their families in a policy of assimilation which only ended in the 1970s. In some states it was part of a policy “to breed out the colour” – in the words of Cecil Cook, who held the title of Chief Protector of Aborigines in the Northern Territory in the 1930s.

Prime Minister Rudd moved:

“That today we honour the Indigenous peoples of this land, the oldest continuing cultures in human history.

We reflect on their past mistreatment.

We reflect in particular on the mistreatment of those who were Stolen Generations – this blemished chapter in our nation’s history.

The time has now come for the nation to turn a new page in Australia’s history by righting the wrongs of the past and so moving forward with confidence to the future.

We apologise for the laws and policies of successive Parliaments and governments that have inflicted profound grief, suffering and loss on these our fellow Australians.

We apologise especially for the removal of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children from their families, their communities and their country.

For the pain, suffering and hurt of these Stolen Generations, their descendants and for their families left behind, we say sorry.

To the mothers and the fathers, the brothers and the sisters, for the breaking up of families and communities, we say sorry.

And for the indignity and degradation thus inflicted on a proud people and a proud culture, we say sorry.

We the Parliament of Australia respectfully request that this apology be received in the spirit in which it is offered as part of the healing of the nation.

For the future we take heart; resolving that this new page in the history of our great continent can now be written.

We today take this first step by acknowledging the past and laying claim to a future that embraces all Australians.

A future where this Parliament resolves that the injustices of the past must never, never happen again.

A future where we harness the determination of all Australians, Indigenous and non-Indigenous, to close the gap that lies between us in life expectancy, educational achievement and economic opportunity.

A future where we embrace the possibility of new solutions to enduring problems where old approaches have failed.

A future based on mutual respect, mutual resolve and mutual responsibility.

A future where all Australians, whatever their origins, are truly equal partners, with equal opportunities and with an equal stake in shaping the next chapter in the history of this great country, Australia.” (‘Apology to Australia’s Indigenous peoples’).

Reaction from die-hard ‘conservatives’ went from Peter Dutton’s, now a powerful minister of the Turnbull Government. (On 18 July 2017 he was named Minister for Home Affairs, a newly created portfolio giving him oversight of Australian Security Intelligence Organisation, the Australian Federal Police and Border Force. In opposition at the time, Dutton offered to resign rather than attend the delivery of the Apology). Former Prime Minister Abbott repeatedly referring ever since to the modern practice of acknowledging traditional owners as “out-of-place tokenism.” Such attitude also won support among some Indigenous leaders, who have described the trend as “paternalistic”.

Of course, some Indigenous People might have been correct from the word start, accusing the Apology of being ‘paternalistic’. There may be some truth in that. Rudd’s Apology was delivered fairly unemotionally – perhaps a clear sign of self-control in a difficult situation. Most importantly, though, there was no mention then or thereafter of reparation.

In civilised countries the concept of tort carries to legal liability and is invariably linked to compensation. On that 13 February 2008 in Australia, not a word about it!

On 23 July 2008 the Commonwealth Government conducted a community Cabinet meeting in eastern Arnhem Land. Prime Minister Rudd was presented with a Statement of Intent on behalf of Yolngu and Bininj clans living in Galiwin’ku, Gapuwiyak, Gunyangara, Laynhapuy, Maningrida, Milingimbi, Ramingining and Yirrkala homelands – approximately 8,000 Indigenous People in Arnhem Land. The ensuing communiqué argued that the right to maintain culture and identity and to protect land and sea estates were preconditions for economic and community development in remote communities. The communiqué called on the Government “to work towards constitutional recognition of our prior ownership and rights.” Receiving the communiqué, Prime Minister Rudd also pledged his support for recognition of Indigenous Peoples in the Constitution.

On 24 June 2010 Ms Julia Gillard replaced Rudd on the prime ministership. On 21 August 2010 new elections followed, for which the Australian Labor Party formulated a policy proposing that “constitutional recognition of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples would be an important step in strengthening the relationship between indigenous and non-indigenous Australians, and building trust.” A Gillard Labor Government would establish an Expert Panel on Indigenous Constitutional Recognition comprising Indigenous leaders, representatives from across the federal Parliament, constitutional law experts and members of the broader Australian community.

The Opposition, too, had a ‘Plan for real action for Indigenous Australians’. The plan was very similar to that of the Government and provided that the Coalition [of the Liberal and National parties] would encourage public discussion and debate about the proposed change, and seek bipartisan support for a referendum to be put to the Australian people at the 2013 election.

The Labor Party was re-elected, albeit without a majority. Ms Gillard was confirmed as Prime Minister of a minority government.

In September 2010 agreements were reached by the Gillard minority government with the Australian Greens and three Independent members to hold a referendum “during the [life of the current] Parliament or at the next election on Indigenous constitutional recognition and recognition of local government in the Constitution.”

On 23 December 2010 Prime Minister Gillard announced the membership of the Expert Panel on Constitutional Recognition of Indigenous Australians. The Panel comprised persons from Indigenous and non-Indigenous communities and organisations, small and large business, community leaders, academics, and members of Parliament from across the political spectrum. Membership was drawn from all States and Territories, cities and country areas. The members of the Panel would serve in an independent capacity.

Throughout 2011 the Panel was supported by an executive officer, a media adviser and the Indigenous Constitutional Recognition Secretariat in the Department of Families, Housing, Community Services and Indigenous Affairs.

The Panel met throughout 2011: in Canberra in February, October and November, Melbourne in March, July and December, and in Sydney in May and September; it also conducted much of its work out of session.

The process required:

- the building of a general community consensus;

- the central involvement of Indigenous and non-Indigenous people; and

- the collaboration with Parliamentarians from across the political spectrum.

The Expert Panel was to report by December 2011.

In performing its role, the Panel was to:

- lead a broad national consultation and community engagement programme to seek the views of a wide spectrum of the community, including from those who live in rural and regional areas;

- work closely with organisations, such as the Australian Human Rights Commission, the National Congress of Australia’s First Peoples and Reconciliation Australia who have existing expertise and engagement in relation to the issue; and

- raise awareness about the importance of Indigenous constitutional recognition including by identifying and supporting ambassadors who will generate broad public awareness and discussion.

The Panel was to have regard to:

- key issues raised by the community in relation to Indigenous constitutional recognition;

- the form of constitutional change and approach to a referendum likely to obtain widespread support;

- the implications of any proposed changes to the Constitution; and • advice from constitutional law experts.

At its second meeting in Melbourne in March 2011 the Panel agreed on four principles to guide its assessment of proposals for constitutional recognition of Indigenous and Torres Strait Islander Peoples, namely that each proposal was to:

- contribute to a more unified and reconciled nation;

- be of benefit to and accord with the wishes of Indigenous and Torres Strait Islander Peoples;

- be capable of being supported by an overwhelming majority of Australians from across the political and social spectra; and

- be technically and legally sound.

In its consideration of options for constitutional recognition, the Panel was strictly guided by those four principles.

The Panel worked closely with organisations such as the National Congress of Australia’s First Peoples, Reconciliation Australia and the Australian Human Rights Commission. Congress undertook a number of surveys of its members in relation to recognition of Indigenous and Torres Strait Islander Peoples in the Constitution. Reconciliation Australia undertook activities to complement the work of the Panel. These included contributing content to the Panel’s website, appointing ambassadors and facilitating public meetings.

In May 2011 the Panel published and had distributed a discussion paper. A National Conversation about Indigenous and Torres Strait Islander Constitutional Recognition. The discussion paper identified seven ideas intended to provide a starting point for conversation with the public envisaged by the Panel, but in no way to limit the scope of proposals which might have been raised through the consultation and submissions process.

The Panel set up an interactive website providing an online presence, involved social media including Twitter, Facebook, YouTube, Flickr, Tumblr and a blog feed, and published all submissions on the website unless confidentiality had been requested. The Panel engaged a media adviser to develop a media strategy to inform the public as widely as possible. The strategy included arranging features and opinion pieces, television and radio talkback programmes, and speeches at various events.

Between May and October 2011 the Panel conducted a broad national consultation programme, which included public meetings, individual discussions, presentations at festivals and other events, the website, and a formal public submissions process.

State and local office contacts of the Department of Families, Housing, Community Services and Indigenous Affairs, and other contacts developed lists for each consultation. In developing such lists the Panel concentrated on Indigenous and Torres Strait Islander leaders, business leaders, community leaders, leaders of organisations with Reconciliation Action Plans, and faith-based leaders.

The consultation schedule included meetings with key interested parties, and public consultations in 84 urban, regional and remote locations and in each capital city. It involved as many Indigenous and Torres Strait Islander communities as possible. Wherever possible, at least two Panel members attended each consultation. At most places, the Panel held an initial meeting with local elders before holding a public community consultation and, where achievable, meetings with other community and business leaders. At each consultation, copies of the discussion paper, the Australian Constitution, information kits, and a questionnaire were distributed.

Between May and October 2011 the Panel held more than 250 consultations, in 84 locations, with more than 4,600 attendees.

A short film summarising the discussion paper was translated into 15 Indigenous and Torres Strait Islander languages, namely Alywarra, Anindiyakwa, Arrernte, Guringdji, Kimberley Kriol, Kriol, Kunwinjku, Murrinh–Patha, Pitjantjatjara, Tiwi, TSI Kriol, Walpirri, Warramangu, Wik Mungan and Yolngu.

Between May and September 2011 the Panel received 3,464 submissions from members of the public, members of Parliament, community organisations, legal professionals and academics, and Indigenous and Torres Strait Islander leaders and individuals.

To assist its analysis of the records of consultations and public submissions, as well as to work together closely on the preparation of its report, the Panel established a research and report subgroup. An external consultant, Urbis, was engaged to provide a qualitative analysis of the key issues and themes raised in submissions.

The Panel was aware that, in holding public meetings and inviting written submissions, it would only be able to obtain the views of a small number of Australians. To gather the views of a wider spectrum of the community, and to help build an understanding of the likely levels of support within the community for different options for constitutional recognition, the Panel commissioned Newspoll – by the way, an asset of the ‘Murdoch stable’ – to undertake research. In February 2011 Newspoll tested initial community support by placing a question on its National Telephone Omnibus Survey which asked: “If there was to be a referendum to recognise indigenous Australians in the Australian Constitution, based on what you know now would you vote in favour of it or against it?” In March 2011 Newspoll again tested levels of community support. In August 2011 Newspoll undertook exploratory qualitative research designed to assist the Panel better to understand the views of Australian voters on constitutional recognition of Indigenous and Torres Strait Islander Peoples.

In September and October 2011 Newspoll conducted two nationally representative telephone surveys. The first survey was designed to help the Panel understand the level of support for a broad range of ideas for constitutional change as the Panel’s consultation activities were nearing their conclusion. The second survey aimed to test the Panel’s early thinking on possible recommendations, and was timed to ensure that information on levels of public support was available during November and December while the Panel was deliberating on its final recommendations.

In November 2011 Newspoll conducted a second round of qualitative research designed to assist the Panel in finalising the language of its recommendations, and in future communications about advancing constitutional recognition of Indigenous and Torres Strait Islander Peoples.

The Panel also developed a web survey to test support for ideas raised with it during the consultation period. A link to the survey was provided to people who had given contact details at consultations, and to people on the email databases of the National Congress of Australia’s First Peoples, Reconciliation Australia and the Australian Human Rights Commission.

Between 22 and 30 November 2011 Newspoll conducted four online focus group sessions in relation to possible wording for recommendations. Online focus groups (‘live chats’) included people of different ages, both supportive of and opposed to constitutional recognition of Indigenous and Torres Strait Islander Peoples.

To some extent, submissions to the Panel were constrained by the way ideas were framed in its discussion paper. Discussions at consultations, on the other hand, were less constrained, and options were suggested which had not been canvassed in the discussion paper. As the Panel’s work progressed throughout the year, its thinking about options for recognition developed. In this sense the process was iterative. The quantitative research undertaken by Newspoll also elicited responses to specific questions, which reflected the Panel’s thinking at different stages of the process. To this extent, the Panel recognised that the analysis of consultations, the analysis of submissions and the results of the quantitative research were not directly comparable.

The Panel’s terms of reference included the requirement to advise the Government on the “level of support from Indigenous people” for each option for changing the Constitution. One of the principles adopted by the Panel to guide its assessment of proposals was the need for any proposal “to be of benefit to and accord with the wishes of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples.”

Testing the level of support for any proposal across the entire Indigenous and Torres Strait Islander population would be immensely difficult. No established survey instrument could provide an accurate and representative measure of the opinion of Indigenous and Torres Strait Islander Peoples. At the request of the Panel, the possibility of constructing a statistically representative panel of Indigenous and Torres Strait Islander respondents to a large national survey was investigated, but found not to be feasible.

The Panel placed a strong emphasis upon ensuring that its consultation schedule enabled it to capture the views of as many Indigenous and Torres Strait Islander Peoples and communities as possible within the available timeframes. In addition to the meetings held in the course of the broader consultation programme, the Panel also held high-level focus groups with Indigenous and Torres Strait Islander leaders.

The Panel was also informed by responses to its web survey from people who identified themselves as Indigenous or Torres Strait Islander. The Panel also sought to make use of other sources of information on the views of Indigenous and Torres Strait Islander Peoples, including surveys of its members conducted by the National Congress of Australia’s First Peoples.

Finally, the Panel received submissions from many Indigenous and Torres Strait Islander Peoples and organisations. The views expressed in these submissions assisted the Panel in its discussions and in arriving at its recommendations.

The last of the four principles agreed by the Panel required that any proposal be “technically and legally sound.” This reflected the requirement in the Panel’s terms of reference that suggested changes have regard to “the implications of any proposed changes to the Constitution and advice from constitutional law experts.”

The Panel sought legal advice on options for, and issues arising in relation to, constitutional recognition. Advice was provided by constitutional law experts among the Panel’s members, as well as by leading practitioners of constitutional law. In addition to this advice, legal roundtable meetings were held further to test that the Panel’s proposed recommendations were legally and technically sound.

Submissions were also made to the Panel by many legal practitioners, academics and professional associations. These submissions assisted the Panel in its discussions and in forming its recommendations.

To test community responses to its proposed recommendations, the Panel adopted a number of strategies, including engaging Newspoll.

The Panel also held a series of high-level focus groups in October and November 2011 with Indigenous and Torres Strait Islander leaders in order further to test proposed recommendations. The lists of interested persons which had been developed for the purpose of consultations were drawn on to invite participants to the Indigenous and Torres Strait Islander focus groups. Focus groups were held in Adelaide, Brisbane, Broome, Cairns, Canberra, Darwin, Hobart, Melbourne, Perth, Sydney and Thursday Island.

These discussions were an important step in obtaining the views of Indigenous and Torres Strait Islander Peoples in relation to the Panel’s proposed recommendations.

Legal roundtables were also held further to test proposed language for unintended consequences. Six such roundtables were held: one in Brisbane, one in Perth, two in Melbourne and two in Sydney. These were attended by some 40 barristers and academics with expertise in constitutional law.

Roundtables with officials from multiple government agencies were held in Brisbane and Melbourne. A roundtable discussion was also held in Sydney, attended by twenty representatives from nongovernmental organisations.

The result of so much activity was a report, divided into eleven chapters, with four appendices, an abundant bibliography and a good index. After an introduction, the chapters present a historical background, a comparative and international recognition, the national conversation dealing with themes from the consultation programme, forms of recognition, the ‘race’ provision contained in the Australian Constitution, considerations on racial non-discrimination, on governance and political participation, on agreement-making, approaches to the referendum and finally a draft Bill.

The Report barely touched upon the claim for ‘sovereignty’ by Indigenous Peoples. It observed, correctly (?), that sovereignty is explained in ways and with concepts quite varied even amongst Indigenous Peoples. In addition, qualitative research undertaken by the Panel in August 2011 found that the concepts of ‘sovereignty’ and ‘self-determination’ were poorly understood by non-Indigenous Australians and, anyway, any proposal on the subjects would have been unlikely to satisfy the fourth of the Panel’s principles, namely the requirement that such proposal be “technically and legally sound.”

On this matter of ‘sovereignty’ the Report reveals the clash between some of the beliefs of Indigenous Peoples and the language used, not only in the Report but in the everyday conversation of ordinary non-Indigenous Australians.

The difficulty, almost impossibility, of reconciling current non-Indigenous values with the strongly held beliefs by Indigenous People is glaringly demonstrated by the contents of a statement of Yolngu law which was submitted to the Panel by one of its members: Timmy Djawa Burarrwanga of the Gumatj clan.

The statement, which appears even before the introduction to the Report, reads:

“It is really sad that non-Aboriginal people do not understand about our law. We cannot have traditions unless we know and respect ngarra rom and mawul rom. Ngarra rom is our law. Mawul rom is the law of peace-making. We hold ngarra rom in our identity. We have never changed our laws for thousands of years. It is like layers and layers of information about our country. Ngarra rom works to enable government within the various Aboriginal nations, led by the dilak, or clan leaders. Ngarra rom also governs relations among nations. Ngarra is also a knowledge system. Under ngarra, there are djunggaya or public officers who make business go properly. There are djunggaya all over this country – for Yolngu, Arrernte, Walpirri, Murri, Koori and Noongar and all the Aboriginal nations. We Yolngu have ngarra or hidden knowledge. Ngarra holds the Yolngu mathematical system about relationships among all people, beings and things in the world – land, sea, water, animals, plants, the wind and the rain, and the heavens. We Yolngu have never been anarchists or lawless. The Constitution in 1901 did not change ngarra. In 1901, the Constitution ignored ngarra rom. Without acknowledgment in the Constitution, there is lawlessness and anarchy. Without acknowledgment in the Constitution, we are separate. The preamble to the Constitution is a short job. The Constitution is a barrier to understanding the indigenous cultures of this country. No more British preamble. Let us be together in the Constitution to make unity in this country. This means ‘We are one. We are many of this country’. Timmy Djawa Burarrwanga, Gumatj Clan.

Continued Monday with: A belated ‘Recognition’ and a ‘new policy’ (Part 2)

Previous instalment: The new invasion of the Northern Territory (Part 3)

Dr. Venturino Giorgio (George) Venturini, formerly an avvocato at the Court of Appeal of Bologna, devoted some sixty years to study, practice, teach, write and administer law at different places in four continents.

Dr. Venturino Giorgio (George) Venturini, formerly an avvocato at the Court of Appeal of Bologna, devoted some sixty years to study, practice, teach, write and administer law at different places in four continents.

Like what we do at The AIMN?

You’ll like it even more knowing that your donation will help us to keep up the good fight.

Chuck in a few bucks and see just how far it goes!

Your contribution to help with the running costs of this site will be gratefully accepted.

You can donate through PayPal or credit card via the button below, or donate via bank transfer: BSB: 062500; A/c no: 10495969

4 comments

Login here Register here-

paul walter -

paul walter -

paul walter -

diannaart

Return to home pageThe biggest disappointment for me with the early Rudd government, apart from not standing up for the ABC, was the refusal to repudiate The Intervention and start afresh with substantial policies deriving of ideas derived of Mabo and Wik and the Little Children are Precious line; ideas that could deliver a tangible improvement for Indigenes based on respect for THEIR rights and needs including for privacy and respect.

https://theconversation.com/ten-years-on-its-time-we-learned-the-lessons-from-the-failed-northern-territory-intervention-79198

The Intervention itself was travesty of Little children Are Sacred, a crude attempt by a failing government to repeat the propaganda success of Kids Overboard/Tampa. Why on Earth did Rudd and Macklin not refute it but continue its implementation after gaining government?

Paul

May I suggest you listen to Waleed Ali and Scott Stehpens’ excellent podcast, “The Minefield” from this week which critically examines many of the issues you raise and then some.

http://www.abc.net.au/radionational/programs/theminefield/what-good-did-the-apology-do/9443490