The ALP – Arguing for a Minimum Program

The ALP has long been characterised by internal ideological divisions between self-identifying social democrats and self-identifying socialists. This division has always problematic because there are competing definitions of social democracy and socialism. Sweden has been described both as socialist and social democratic. Democratic socialists always contested the notion that the former Eastern Bloc represented ‘real socialism’. Other socialists continued to find inspiration in one or another form of Leninism. Some self-identifying social democrats simply see their politics as ‘progressive but moderate’. In a relative sense we think here of a ‘traditional social democracy’. Other social democrats identify as ‘revolutionary social democrats’: basically a continuation in the tradition of early Marxism (before Leninism, and typified to a degree by the example of Austrian social democrats in the 1917-1934 period). This paradigm of socialism (the Austrian example specifically) is notable for adherence to revolutionary aims, even if pitched as ‘revolutionary reforms’ or ‘slow revolution’. It is not opposed to socialism (or democracy) as such – but rather is a reclamation of an old politics where ‘socialism’ and ‘social democracy’ were not opposed to each other.

The question I intend to explore here is ‘what is a reasonable minimum program for the ALP, which brings together the Party’s diverse ideological elements?’. What elements of a Party program should all members of the ALP share adherence to? This is no easy question to answer: as there must be a degree of ‘give and take’, but without compromising on certain basic issues. There’s also the question of what the modern ALP Left should stand for: and whether or not it is also ‘losing its way’.

The ALP used to adhere – in theory – to its own ‘Socialist Objective’. This was always complicated by the so-called ‘Blackburn Amendment’ which committed itself to socialisation to the extent of eliminating “exploitation and other anti-social features”. It was long considered by some as a ‘dead letter’; at odds with the practice of actual Labor policy and containing a contradiction: at least as far as Marxism is concerned. For Marxism exploitation is structurally inbuilt in capitalism (expropriation of surplus value) and socialisation must be absolute to eliminate it entirely.

Arguably the Objective was also at odds with political practice on the ALP Left; despite the Left fighting tooth and nail for many years to preserve it. When arguing for the preservation of the Objective Left leaders such as Kim Carr watered down their arguments to the point where there was a very significant loss of meaning and content – in an attempt to broaden its appeal. Guy Rundle has described Carr’s project as one of ‘national social democracy’ characterised by greater self-reliance in manufacturing. But does this meet appropriate minimum requirements as a ‘stream of socialism’? Meanwhile, Rundle portrays the rest of the party as embracing “distributionism” which aims to broaden economic ownership, including a place for co-operatives, but does not aim to negate capitalism’s core dynamics.

This means more than competition and markets; it means accumulation of capital and hence political power in the hands of a dominant capitalist class – achieved through economic relations of exploitation. Meanwhile avowed ‘Third Way’ politics water down social democracy itself – even in the traditions of ‘mixed economy and welfare state’ – to the point of meaninglessness.

For socialists in the Labor Party the reality is we cannot have it all our way. And there are questions as to what ALP Left politics are really about these days anyway. Cynics might argue that in practice the ALP Left simply stands for “a slightly bigger welfare state and social wage”; and “a slightly more progressive tax system”. Though incremental improvement of welfare, progressive tax and the social wage is desirable if the progress is sustained. The Left itself needs its own statement of beliefs: which involve a more fundamental critique of capitalism. This might include critiques of monopolism, exploitation, alienation created by physically demanding work, and work involving lack of creative fulfilment and control, as well as economic cycles and crises, and the distribution of political and economic power. But these could also include building blocks for the broader Party.

To begin it is worth considering the common ground between different schools of socialism and social democracy in terms of a minimum program. This would be inclusive of a steadily expanding social wage and welfare state – preferably to Nordic proportions (in the sense that was realised at the height of Nordic social democracy). Though Nordic Social Democracy has long been in retreat, and this means we need to take their example with a grain of salt. This means more robust pensions: comprehensive socialised health (including Medicare Dental) and appropriate subsidies for services and amenities fundamental to modern human existence. This includes power, water, socialised or co-operative housing, communications (including internet access), transport, availability of nutritious food, and so on. Ongoing Education is also crucial to modern life; and all people ought to be able to pursue personal fulfilment through education as well as skilling up to meet labour market requirements.

While the reality is that the modern labour market is characterised by exploitation (workers do not keep the full proceeds of their labour power), we do operate in a global economy where it is necessary to sell labour power in order to participate. Right now there is ‘no way out’ of capitalism, but that does not mean we cannot have a critique which informs strategies which address the anti-social, irrational and unfair features of the system. The Left should have a critique – including of the core workings of capitalist political economy and it needs a code of principles which provides this, but a minimum program for a wide range of socialists and social democrats also needs to account for an alliance of forces including elements who are not committed to negating capitalism, even far into the future.

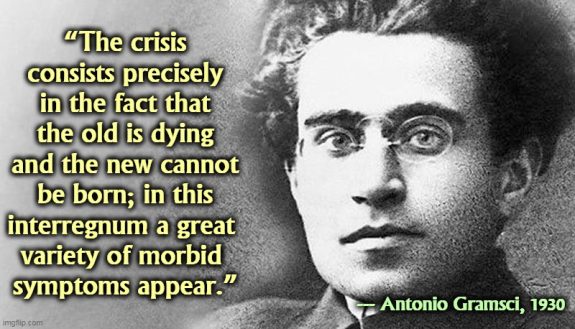

Something needs to change in discourse more broadly – with an effective counter-hegemony – to achieve anything like a consensus on a Socialist Objective within the ALP. This means we need a mobilised Left fighting to challenge ‘common sense’ ideas both within and outside of the Party. Arguably the Communist Party of Australia used to play this role very effectively, as did other Western Communist Parties – even though they did not usually enjoy significant electoral success. (The Communist Party of Italy – the PCI – is a very important exception; having won very strong electoral success for many decades.)

That said, a minimum program could include a commitment for the foreseeable future to a democratic mixed economy, or a hybrid system. Strategic socialisation should be pursued for reasons of economic efficiency, equity, and sovereignty. In areas characterised by a lack of competition, or by collusion – government business enterprises can be a game changer. Think banking, general insurance, health insurance, postal services. In other areas it is appropriate to have natural public monopolies. Infrastructure in energy, water, communications, transport are other areas where the logic of natural public monopoly ought to apply. Public monopolies in these fields translate into reduced cost structures; with the benefits flowing on to the economy more broadly, including consumers. Governments – including Labor Governments – have systemically undermined the place of natural public monopoly in the economy.

But we need a debate on this within the Party, about a commitment to strategic public ownership and if possible, to natural public monopoly in specific fields such as water, energy, transport and communications infrastructure as well as a restoration of a public sector job network after the example of the old CES.

Still, it is hard enough already getting many self-identifying ‘moderate’ social democrats to even agree to restoring a public sector role in these fields (in competition with private enterprise), let alone restoration of natural public monopolies. Nonetheless the Left should lead a debate on natural public monopoly and strategic (including competitive) government business enterprise. Specifically, a minimum program should refer to a democratic mixed economy, and this should frame an internal debate which the Left tries to lead. Government could also invest in primary industries; and in Australia especially there is great scope to benefit from a public role in minerals exploration and mining. Billions in revenue could be directed towards social programs.

Co-operatives could also play a central role in a democratic mixed economy, and as far as they reach, they attack economic exploitation at its very roots. It’s important to observe, however, that even in Spain where the successful Mondragon Co-operative operates – that co-operative ownership is not very significant in the context of the broader economy. But particularly, in Australia government could underwrite co-operative enterprise to enable it to remain competitive on global and local markets, including by investment in Research and Development and economies of scale. Government could also provide cheap loans to facilitate the establishment of co-operatives, including smaller scale co-operatives – eg: co-op cafes – which not only attack exploitation but which also allow intimate creative control by workers.

Strong policies could secure a significant (as opposed to marginal or minimal) place for co-operatives in the Australian economy. But importantly, co-operative enterprise is not a substitute for the public sector: both play a core role in a democratic mixed economy. Commitment to promoting a greater and greater role for co-operatives in the economy needs to be integrated in a minimum program.

Other areas where an agenda of popular and workers control could be advanced include co-determination and collective capital mobilisation. In Australia superannuation funds have become powerful players in investment. Though they operate in the capitalist context; and tend to adhere therefore to capitalist imperatives (eg: share value maximisation) hence they advance a distributionist agenda, but not much which is more radical. Also, public pension funds would have been more equitable, and the superannuation system threatens the eventual marginalisation and undermining of the public Aged Pension over time.

Meanwhile, co-determination can manifest either as consultation, or in the sense of all parties having to agree on major decisions. In Australia the starting point would be workers’ representatives on company boards. Hence workers could have ‘an insiders’ view’ on the decisions affecting their productive lives. This specific strategy would not be radically transformative in the sense of workers’ control, but it would be a step forward. Again, we need to set the broad framework in a minimum program, and then for the Left to lead a debate within that framework.

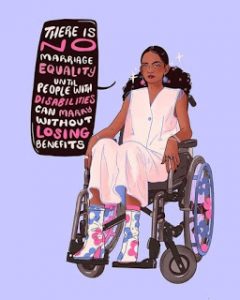

There is a broad scope to reform welfare. Labor should also be committed to strengthening the Aged Pension, Disability Pension, Job Seeker’s Allowance, Sole Parents’ Pension, Austudy, and other welfare. The Disability Pension (and National Disability Insurance Scheme supports) should be for life – in the sense of not being withdrawn depending on age. Also, there should be more scope to earn additional income through casual or part-time work (or other means) without losing the Disability Support Pension. And entering into a relationship should not see a substantial portion of welfare payments withdrawn. The NDIS should be strengthened more broadly, also not undermined. University fees should be replaced by progressive tax levies which effectively relate proportionately to the actual financial advantage gained. A Garaunteed Minimum Income relating to the cost of all fundamental needs could consolidate basic universal economic rights.

In a minimum program reference could be made to all pensions; and the imperative of providing them on the basis of need (again perhaps expanded, and then indexed quarterly to inflation or cost of living – whichever is greater). The debate on a Garaunteed Minimum Income can be won, but it may take time to integrate it into a Minimum Program.

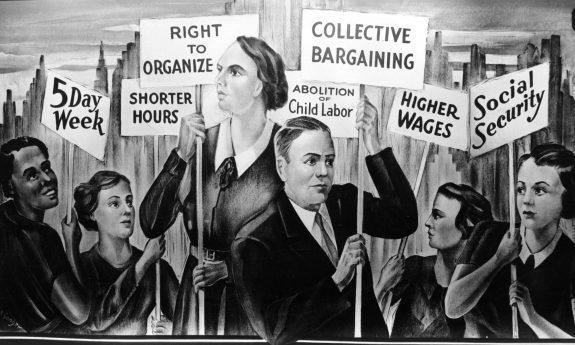

Finally, there are issues of human rights, labour market and industrial relations rights, and housing – which also need to be addressed in a Minimum Program. Labor needs to be unequivocal in a Minimum Program in its commitment to freedom of association, assembly and speech, as well as the right to basic needs such as housing, heating, cooling, nutrition, education, health services, access to transport services, and access to communications and information technology. This needs to be amended as new relative rights and needs arise with technological and economic progress. The right to engage in Pattern Bargaining and to withdraw labour in good faith (whether for industrial or political goals) needs to be promoted, and at the lower end of the labour market especially more robust minimum standards and regulation need to be provided for. This should have a substantial effect if implemented in the case of heavily exploited ‘feminised’ industries.

Again, shelter is a human right, and government policy (including provision of public housing) should seek to achieve its universal fulfilment. Government could also help facilitate co-operative housing, and affordable housing – through subsidies and regulations. The Federal Government and the States have long lagged behind here, and support from the Federal Government especially is needed – as they do not endure the same fiscal constraints as do the other tiers. Recently there has been a trend to promote ‘affordable’ housing (as an alternative to public housing) through deals with private developers, but while this strategy can provide better outcomes for some renters, it does not achieve either efficient financing or equity compared with public housing.

Labor needs a minimum program which significantly expands an ongoing policy of building enough high-quality public housing to meet the demand; while looking to the Austrian example to destigmatise public housing and establish it as an option for all Australians, including but not limited to the most disadvantaged. A minimum program needs to aspire to this, and it should not be controversial for genuine social democrats and socialists.

In conclusion Labor also needs an independent foreign policy outlook and a humane policy with regards to rights of asylum seekers. We should lead the way on defusing conflicts between China and the United States and heading off any potential war. And there is no place for Mandatory Detention in any Party of the broad Left. We should also promote ‘deep democracy’, supported through civics education ‘for active, informed and critical citizenship’ and government programs which put active citizenship at the centre of policy. This could include government funding to access public space – including, for instance shopping centres – where political and social movement organisations across most of the spectrum could promote their own ideas of ‘active citizenship’.

In short – and to summarise in conclusion – a Minimum Program should promote a progressively expanding social wage and welfare state, as well as a democratic mixed economy – with stronger public and democratic sectors which aim to improve underlying cost structures to the benefit of the broader economy and consumers – through strategic public ownership. Here, the social wage includes socialised health and education and ensuring universal access to shelter (including public housing), information and communications technology, transport services, and a minimum income where access to energy and water is also universal. And with a steadily more progressively-structured tax system – with an open commitment to just economic redistribution. And we will define the welfare state’s role as comprising social provision of income – especially the vulnerable – with cross-over between welfare state and social wage where it comes to social services.

Also, the minimum program should include reference to the progressive expansion of economic democracy on several fronts, and the provision of fundamental industrial and broader human rights. This means a regulated labour market and the right to withdraw labour in good faith for industrial or political purposes. As well as the minimisation of the anti-social complications of capitalism: including its crisis-prone nature; its tendency to concentrate wealth and promote monopolism; as well as problems of inbuilt obsolescence – and of collusion and other anti-competitive or anti-consumer practices. Also ‘the market’ does not necessarily ‘organically’ provide for human need – though there is a role for it in providing for the flexible satisfaction of individualised needs structures. The need for choice – and hence competition – means there are limits to socialisation – at least under current conditions. ‘The market’ has a place but so too does social provision which goes beyond ‘market logic’.

This article has sought to explore the issues which should inform a minimum program for the ALP. It should be possible to win broad agreement on most of this article’s broad tenets. In other areas the article has outlined areas where minimum policies could be applied, but where the Left should lead the debate in terms of achieving stronger policies.

Also importantly, there are limits to purely electoral politics – and there is a need for an organised counter-hegemony. The counter-hegemony should seek a more radical reframing of debate and issues than the minimum program, and it is necessary to build an alternative to the old Western Communist Parties who used to contest ‘political and economic common sense’. But that is beyond the broad scope of this article.

The point is that it is possible to achieve broad agreement on a minimum program which mobilises the broad Labor Party and frames its policies. The minimum program, here, attempts to frame the ALP as involving currents ranging from traditional social democratic (mixed economy, labour rights and welfare state) on the relative right, to democratic socialism and revolutionary social democracy on the Left (involving a more ambitious agenda of economic democracy and socialisation) And these various currents are considered as being capable of solidarity behind basic programmatic and policy principles and agendas. The most diluted ‘Third Way’ positions – which stand for little in terms of the traditions of social democracy or socialism – need to be seen as liquidationist – and hence are not accepted within the framework of the minimum program.

It is hoped that this article will promote debate and influence the development of the ALP’s Platform running up to the next National Conference. And also, the development of a program behind which both elements of the ALP Left and the ALP Right might be able to coalesce, as well as non-aligned elements. This goes so far is to problematise the very idea of an ‘ALP Right’ which is right-wing on the broader political spectrum. Even the most relative right-wing elements in the ALP should be relatively Left on the broader spectrum. We all need to see ourselves as part of a ‘broad Left’, and in this sense having common cause. Once we agree on this perhaps we can truly ‘move forward together’.

Note: I have been an ALP member for over 30 years.

This article was originally published on ALP Socialist Left Forum.

Like what we do at The AIMN?

You’ll like it even more knowing that your donation will help us to keep up the good fight.

Chuck in a few bucks and see just how far it goes!

Your contribution to help with the running costs of this site will be gratefully accepted.

You can donate through PayPal or credit card via the button below, or donate via bank transfer: BSB: 062500; A/c no: 10495969

This would inevitably involve tax reform. Ideally Labor should be aiming to reform progressive tax to the tune of 5% of GDP over 10 years, or at least three terms of Federal Government. This would bring us closer to OECD average levels of tax and social expenditure. Rolling back unfair means testing of pensions – including Disability Pensions – would empower hundreds of thousands of women and men with greater independence; and if we are concerned about equity we need to reform tax in other areas for people with higher incomes. It would also empower those people to enter into relationships without fear of destitution. Eligibility tests should also be relaxed so those incapable of full time work are not threatened with exclusion.

This would inevitably involve tax reform. Ideally Labor should be aiming to reform progressive tax to the tune of 5% of GDP over 10 years, or at least three terms of Federal Government. This would bring us closer to OECD average levels of tax and social expenditure. Rolling back unfair means testing of pensions – including Disability Pensions – would empower hundreds of thousands of women and men with greater independence; and if we are concerned about equity we need to reform tax in other areas for people with higher incomes. It would also empower those people to enter into relationships without fear of destitution. Eligibility tests should also be relaxed so those incapable of full time work are not threatened with exclusion.