Skewed Responsibility: Australian War Crimes in Afghanistan

The Inspector-General of the Australian Defence Force Afghanistan Inquiry was always going to make for a gruesome read – and that was only the redacted version. The findings of the four-year investigation, led by New South Wales Court of Appeal Justice and Army Reserve Major-General Paul Brereton, point to “credible evidence” that 39 Afghan non-combatants and prisoners were allegedly killed by Australian special forces personnel. Two others were also treated with cruelty. The Report recommends referring 36 cases for criminal investigation to the Australian Federal Police. These involve 23 incidents and 19 individuals who have been referred to the newly created Office of the Special Prosecutor.

The Report goes into some detail about various practices adopted by Australia’s special forces in Afghanistan. The initiation rites for junior soldiers tasked with “blooding” – the first kill initiated by means of shooting a prisoner – come in for mention. “This would happen after the target compound had been secured, and local nationals had been secured as ‘persons under control’.” “Throwdowns” – equipment such as radios or weapons – would then be placed upon the body. A “cover story” would thereby be scripted “for purposes of operational reporting to deflect scrutiny.”

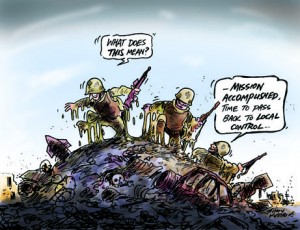

A “warrior culture” also comes in for some withering treatment, which is slightly odd given the kill and capture tasks these men have been given with mind numbing regularity. “Special Force operators should pride themselves on being model professional soldiers, not on being ‘warrior heroes’.” When one is in the business of killing, be model about it.

As with any revelation of war crimes, the accused parties often express bemusement, bewilderment and even horror. The rule at play here is to always assume the enemy is terrible and capable of the worst, whereas somehow, your own soldiers are capable of something infinitely better. “I would never have conceived an Australian would be doing this in the modern era,” claimed Australian Defence Force Chief General Angus Campbell.

History has precedent for such self-delusions of innocence abroad. The atrocity is either unbelievable, or, if it does take place, aberrant and capable of isolation. The killing of some 500 unarmed women, children and elderly men in the Vietnamese hamlet of My Lai on March 16, 1968 by soldiers of the US Americal Division was not, at least initially, seen as believable. When it came to light it was conceived as a horror both exceptional and cinematic. A veteran of the Twenty-Fifth Infantry Division went so far as to regard My Lai as “bizarre, an unusual aberration. Things like that were strictly for the movies.”

The investigating subcommittee of the House Armed Services Committee responded to My Lai in much the same way, suggesting a lack of sanity on the part of the perpetrators. The massacre “was so wrong and so foreign to the normal character and actions of our military forces as to immediately raise a question as to the legal sanity at the time of those men involved.”

The Brereton Report also has a good deal of hand washing in so far as it confines responsibility to the institution of the army itself. “The events discovered by this Inquiry occurred within the Australian Defence Force, by members of the Australian Defence Force, under the command of the Australian Defence Force.”

Even here, troop and squadron commanders, along with headquartered senior officers, are spared the rod of responsibility. The Report “found no evidence that there was knowledge of, or reckless indifference to, the commission of war crimes, on the part of commanders at troop/platoon, squadron/company or Task Group Headquarters level, let alone at higher levels such as Commander of Joint Task Force 633, Joint Operations Command, or Australian Defence Headquarters.”

Such a finding seems adventurously confident. If accurate, it suggests a degree of profound ignorance within the ADF command structure. For his part, Campbell acknowledged those “many, many people at all sorts of levels across the defence force involved in operations in Afghanistan or in support of those operations who do wonder what didn’t they see, what did they walk past, what did they not appreciate they could have done to prevent this.”

The Report also sports a glaring absence. The political context in terms of decisions made by Australian governments to use such forces drawn from a small pool is totally lacking. Such omissions lend a stilted quality to the findings, which, on that score, prove misleading and patently inaccurate. Armies, unless they constitute the government of a state, are merely the instruments of political wish and folly. Nonetheless, the Report insists that, “It was not a risk [the unlawful killings] to which any government, of any persuasion, was ever alerted. Ministers were briefed that the task was manageable. The responsibility lies in the Australian Defence Force, not with the government of the day.”

Prime ministerial and executive exemption of responsibility is thereby granted, much aided by the persistent fiction, reiterated by General Campbell, that Australian soldiers found themselves in Afghanistan because the Afghans had “asked for our help.”

History may not be the ADF chief’s forte, given that the government at the time was the Taliban, accused of providing sanctuary to al Qaeda’s Osama bin Laden, responsible for the 9/11 attacks on the United States. Needless to say, there was no invitation to special forces troops of any stripes to come to the country. The mission to Afghanistan became a conceit of power, with Australia’s role being justified, in the words of the Defence Department’s website, to “help contain the threat from international terrorism”.

It is also accurate to claim that Australian government officials were unaware of the enthusiastic, and sometimes incompetently murderous activities of the SAS in the country. On May 17, 2002, Australian special troops were responsible for the deaths of at least 11 Afghan civilians. They had been misidentified as al-Qaeda members. The defence minister at the time, Robert Hill, told journalist Brian Toohey via fax that the special forces had “well-defined personnel identification matrices” including “tactical behaviour,” weapons and equipment. These suggested the slain were not “local Afghan people.” This turned out to be nonsense: the dead were from Afghan tribes opposed to the Taliban.

John Howard, the prime minister responsible for deploying special operations troops to Afghanistan in 2001, is understandably keen to adopt the line of aberrance in responding to the Report’s findings. The ADF was characterised by “bravery and professionalism,” and the disease of atrocity and poor behaviour could be confined to “a small group of special forces personnel who, it is claimed, amongst other things, were responsible for the unlawful killing of 39 Afghan citizens.”

This is much wilful thinking, though it will prove persuasive to most Australian politicians. In Canberra, there are few voices arguing for a spread of responsibility. One of them is the West Australian Greens Senator Jordon Steele-John. “The politicians who sent [the special forces] to #Afghanistan & kept them there for over a decade,” tweeted the sensible senator, “must be held to account, as must the chain of command who either didn’t know when they should’ve or knew & failed to act.”

#WarCrimes This isn't just a about 'a couple of rogue #SAS soldiers'

The politicians who sent them to #Afghanistan & kept them there for over a decade must be held to account, as must the chain of command who either didn't know when they should've or knew & failed to act #AusPol

— Senator Jordon Steele-John (@SenatorJordon) November 18, 2020

Like what we do at The AIMN?

You’ll like it even more knowing that your donation will help us to keep up the good fight.

Chuck in a few bucks and see just how far it goes!

Your contribution to help with the running costs of this site will be gratefully accepted.

You can donate through PayPal or credit card via the button below, or donate via bank transfer: BSB: 062500; A/c no: 10495969