Beyond the ‘Palace Letters’ (part 3)

By Dr George Venturini

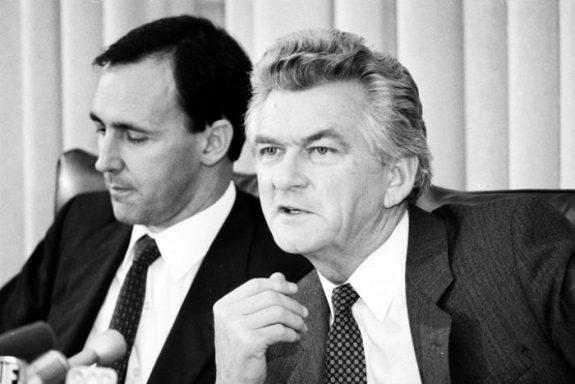

At the election of 2 March 1996 Labor suffered a landslide defeat at the hand of to John Winston Howard’s Liberal–National Coalition. Keating’s personal approval rating had reached historically low levels in his second term, with opponents portraying him as elitist and out of touch. He left parliament after the election, but in retirement has remained active as a political commentator.

It is perhaps extraordinary that the Labor Party turned to Neo-liberalism as a new programme of government, but then one would understand, simply by glancing at the presence in Australia of Socialisme sans doctrines – Métin called it – Socialism without doctrine, as already seen.

It did not matter much to the new Labor leadership that neo-liberalism was first tried in Chile by the Pinochet gang which assassinated the Allende presidency and with it Chilean democracy. That ‘new way’ was coming out of the Chicago School headed by Milton Friedman. And was the first, real 9/11. If it means anything nowadays, neo-liberalism, it signifies the shifting from a moderate form of liberalism to a more radical and laissez-faire capitalist set of ideas. It is closer to the theories of Mont Pelerin Society economists Friedrich Hayek and James M. Buchanan, and it is unforgettably connected with the reactionary excesses of the Margaret Thatcher and Ronald Reagan administrations.

After Pinochet’s installation in Chile, other countries followed. One of the worst examples is Mexico. There, wages declined 40 to 50 per cent in 1984, the first year the North American Free Trade Agreement, N.A.F.T.A. agreement came into force. The cost of living rose by 80 per cent. Over 20,000 small and medium businesses failed. More than 1,000 state-owned enterprises have been privatised in Mexico. It is not possible to disagree with the view that Neo-liberalism meant the neo-colonisation of Latin America.

What scholarly theorising meant to American air traffic controllers in 1981 is still vivid in memory: on 3 August that year, after failing to reach any settlement with the Federal Aviation Administration, the Professional Air Traffic Controllers Organization, P.A.T.C.O. employees went on strike, with about 13,000 of the 17,500 P.A.T.C.O. members walking off the job. This strike was in direct contravention of a federal law which specifically banned strikes by government unions and a no-strike clause in each of their individual employment contracts. That same day, then-president Ronald Reagan called the strike a ‘peril to national safety’ and warned strikers that they were in violation of the law and that their employment would be terminated if they did not return to work within 48 hours. A mere ten percent, about 1,300, of the striking workers returned to work within the allotted two days.

Approximately 3,000 supervisors and 900 military controllers joined the non-striking workers. The people working as air traffic controllers were ready to work 60-hour work weeks. About half of the normally scheduled flights were able to take to the air.

On 5 August 1981 the 11,345 remaining striking air traffic controllers were fired and banned from any future federal employment for life. Lane Kirkland, president of the American Federation of Labor and Congress of Industrial Organizations, AFL-CIO called Reagan’s action ‘brutal overkill’. The International Federation of Air Traffic Controllers contemplated a boycott of United States air traffic in support of P.A.T.C.O., but, with the exception of a two-day boycott by Canadian and Portuguese controllers, no action was taken.

The firing of striking workers and replacing them with supervisors and strike-breakers was by no means a new idea. This was a tactic often used in many industries. Typically, the new contract negotiated included a ‘return to work agreement’, in which the striking workers were re-hired with full seniority and, sometimes, with back pay.

P.A.T.C.O. leaders were gaoled for ignoring the court injunction prohibiting the strike. The United States Justice Department issued indictments against 75 controllers. Fines totalling $1 million per day were levied against the union. The union’s strike fund, consisting of over $3 million, was frozen. On 22 October 1981 the Federal Labor Relations Authority decertified P.A.T.C.O. The union was dead.

Prime Minister Hawke had learned something, and put it into practice at the time of the 1989 Australian pilots’ dispute. That was one of the most expensive and dramatic industrial disputes in Australia’s history. It was co-ordinated by the Australian Federation of Air Pilots, A.F.A.P. after a prolonged period of wage suppression, to support its campaign for a large pay increase – quantified at 29.47 per cent.

The dispute began affecting the public on 18 August 1989 with pilots working ‘9-to-5’. It was never formally resolved due to the mass resignation of pilots, cancellation of their award and de-recognition of their union.

As part of this campaign, A.F.A.P. pilots imposed on their employers (on Australian Airlines, Ansett Australia, East-West, and Ipec) a limitation on the hours they were prepared to work, arguing that if they were to be treated in exactly the same way as other employee groups – as was the Government’s position – their work conditions should also be the same. This initially took the form of making themselves available for flying duties only within the normal office working hours of 9 am to 5 pm.

The dispute severely disrupted domestic air travel in Australia and had a major detrimental impact on the tourism industry and many other businesses. Then, with their awards cancelled by the Industrial Relations Commission and Prime Minister Hawke threatening massive fines and sackings, on 24 August the A.F.A.P. resigned en masse. Two days before Hawke had threatened the pilots: “You go out and it’s war.” Hawke referred to the pilots as “glorified bus drivers” insulting both groups of workers in the process.

He proceeded to scab-herding and what that means in social terms is better explained by Jack London. His famous definition of a scab begins: “After God had finished the rattlesnake, the toad, the vampire, He had some awful substance left with which He made a scab.” Scab-herding is corporate organised crime of a particularly ugly and despicable sort. In the footsteps of Labor Prime Minister Chifley, who sent troops into the mines to break the 1949 coal strike, Prime Minister Hawke declared a national emergency and allowed Royal Australian Air Force planes and pilots and overseas aircraft and pilots to provide services. The R.A.A.F. provided limited domestic air services to ease the impact of the strike. The airlines affected by the strike recruited new pilots from overseas, and for a while, some overseas airlines operated charter 737 and 757 aircraft on the Australian east coast routes. Travel between Perth and Sydney was clumsily re-routed via Singapore, using international flights. The dispute was superficially resolved after the mass resignation of a significant number of domestic airline pilots to avoid litigation from the employers.

The R.A.A.F. ceased ‘public transport operations’ on 15 December 1989, by 31 December 1989 regular leasing of seats on international flights ceased and, by 12 January 1990, the Government ceased its waiver of landing charges. The airlines were able slowly to return to normal schedules as they hired replacement pilots. Thus no specific date can be set for when the dispute stopped impacting flights, tourism and the economy.

Ansett, Australian Airlines, East-West and Ipec no longer exist. East-West was a subsidiary of Ansett in 1989, and was absorbed fully in 1993. Australian Airlines was merged with Qantas in 1992. Ipec was acquired by Toll Holdings in 1998.

The strike crippled the Australian Federation of Air Pilots and cleared the road to airline industry deregulation. Deregulation and rationalisation are code-words for union-busting. Prime Minister Hawke was considering tens of millions in ‘compensation’ to the ‘airline industry’ – a perfect expression of capitalist ‘austerity. And that is the true face of neo-liberalism.

A conclusion is inescapable. Neo-liberalism means this:

1) The notion of ‘the public good’ or ‘the sense of community’ is replaced with the insidious exaltation of ‘individual responsibility’.

Ordinary people, always the poorest in a society, are sent to find solutions to their lack of education, health care, and social security all by themselves. If they fail, they are blamed for being ‘lazy’.

2) For such fundamental change, public expenditure for social services – such as education and health – must be reduced.

3) As a result, the safety net for the needy and the poor must be reduced. Even maintenance of the basic infrastructure – water supply, roads, bridges – is reduced, on the ‘obvious consideration’ that government role in the economy must be reduced and expenditures must be contained. Of course, ‘government assistance’ to business, often in the form of tax benefits, must continue in the interest of production.

4) Deregulation is introduced as essential. Everything which could hinder and/or reduce ‘profit’ – including protecting the environment and secure safety on the job – must be done away.

5) Privatisation is introduced in all fields of production and consumption. To achieve that state-owned enterprises, suppliers of goods and services must be sold to private investors on the unproven mantra that ‘public is bad/private is good’. Such massive sale includes key industries, banks, electricity, railroads, toll highways, schools, hospitals and even fresh water. Usually this is done in the name of greater efficiency, which is often needed, but privatisation has mainly had the effect of concentrating wealth even more in a few hands and making the public pay even more for its needs.

When all this is safely and promptly achieved,

6) The market must be let lose to rule. ‘Free’ enterprise or private enterprise must be allowed to rule. Free from any bonds imposed by the government no matter how much social damage this may cause. There must be greater openness to international trade and investment; wages must be reduced wages by de-unionising workers and eliminating workers’ rights which had been won over many years of struggle. Price controls must be abolished There must be total freedom of movement for capital, goods and services.

The mantra is long and goes like this: an unregulated market is the best way to increase economic growth, which will ultimately benefit everyone.

Benefit everyone? And how could anyone disagree?!

It is Thatcher, Reagan, Hawke and Keating – altogether now: “supply-side” and “trickle-down” economics! Most people are still waiting.

* * * * *

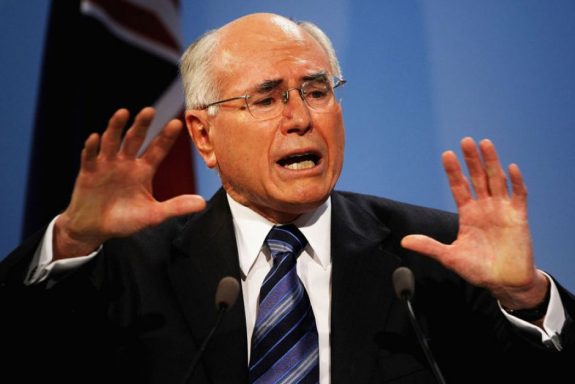

At the federal election of 2 March 1996 John Winston Howard led the Coalition to a sounding victory. From then, and for eleven long years, one may think in terms of ‘restoration’ of old ways.

A solicitor of modest intellectual means but very strong propensity and ability for cunning, he worked his ways through the Liberal Party which culminated to his election for the seat of Bennelong in 1974.

Of Howard it may be said, and very briefly, that he was in effect the Liberal Party’s first pro-market leader in the conservative Coalition and, once elected Leader of the Opposition in 1985, he spent the next two years working to revise Liberal policy away from that of Fraser’s. In his own words he was an “economic radical” and a “social conservative.” In plain English, he was from the beginning a reactionary without many scruples: more than ‘the end justifying the means’, which could in some cases have a certain elegance – an elegance all of its own, Howard had an eye for ‘whatever it takes’.

His governments – of which there were four between 1996 and 2007 – are too recent to be worthy of mention of policy, planning and results.

Some of Howard’s activities, and how he made his mark, may be worth recalling.

Towards the end of what has been portrayed by partisan scribblers and for the benefit of distracted, ignorant readers as ‘the Khemlani affair’, Howard – a recently elected but in a hurry member of the Coalition – worn the respect of the usurper in the Royal Ambush of 11 November 1975.

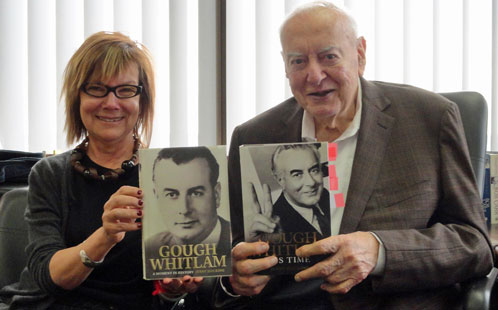

The ‘Khemlani affair’ was a political scandal of Coalition confection which would embarrass the Whitlam Government of Australia in 1975. The government was accused of attempting to borrow money from Middle Eastern countries through the agency of a Pakistani operator by the name Tirath Khemlani, bypassing ‘standard procedures’ of the Australian Treasury.

Now, one should keep in mind that pecunia non olet – “money does not stink”, as a Latin saying goes. Ah, yes, but such money is acceptable at the periphery of the Empire only if it comes through the ‘proper channels.’ And those channels have been ‘traditionally’ to be found only in S.W.1 (London) or – otherwise, if strictly necessary – Wall Street.

S.W.1 is some kind of ‘sacred site’ to the Australian Treasury, because there is the City of London. The City of London Corporation, officially and legally the Mayor and Commonalty and Citizens of the City of London, is the municipal governing body of the City of London, the historic centre of London and the location of much of the United Kingdom’s financial sector.

Many major global companies have their headquarters in the City, including Aviva, BT Financial Group, Lloyds Banking Group, Old Mutual, Prudential, Schroders, Standard Chartered, and Unilever. A number of the world’s largest law firms are headquartered in the City.

And, according to the Australian Treasury, there was the place, and no other, where to seek a loan – if any. Whether in fact those loan providers receive, place, exchange money coming from Middle East sources would not matter. Their money would not stink.

Minerals and Energy Minister Rex Connor wanted funds for a series of national development projects. He proposed that, to finance his plans, the government should borrow $US 4 billion. The minutes authorising the borrowing were signed by the ministers concerned and duly counter-signed by the Governor-General, John Kerr. Was he acting as Queen-proxy? or as Queen John? Hard to say. Contacts had been made on 13 December 1974. Prime Minister Whitlam, his deputy, the Attorney General and the Minister for Mineral and Energy were au fait. Minister Connor had been introduced to a Pakistani dealer by the name of Tirath Khemlani, employed by Dalamal and Sons, a London-based commodity-trading firm.

According to Khemlani, Connor asked for a 20-year loan with interest at 7.7 per cent and set a commission to Khemlani of 2.5 per cent. Despite assurance that all was in order, Khemlani began to stall on the loan, notably after he was asked to go to Zurich with officials of the Reserve Bank of Australia to prove that the funds were in the Union Bank of Switzerland as he had claimed. The government revised its authority to Connor to $2 billion.

The raising of foreign loans for the Australian Government at the time required the authorisation of the Loan Council. It was common knowledge that funds were usually borrowed from European banks or financiers. Connor’s attempt to secure the loan was unusual for several reasons: 1) the size of the loan, 2) the lack of a partnership with foreign investors, which is customary, but was excluded by Connor who wanted Australian resources controlled and owned by Australians, 3) the Minister wanted to raise the loan independently from Treasury, 4) the loan was to come from Arab financiers, not the usual, ‘respectable’ sources based in London – if really necessary, in New York, but no further.

The Middle East at the time was awash with ‘petro-dollars’, as the price of oil quadrupled between 1973 and 1974.

Connor was duly authorised to raise loans through Khemlani in late 1974.

Between December 1974 and May 1975 Khemlani sent an avalanche of regular telexes to Connor advising that he was close to securing the loan.

However, the loan never eventuated and, in May 1975, Whitlam sought to secure the loan instead through a major United States investment bank. As part of the loan procedure, this bank imposed an obligation on the Australian Government to cease all other loan raising activities pertaining to this loan and accordingly, on 20 May 1975, Connor’s loan-raising authority was formally revoked.

As news of the plan leaked, the Opposition began questioning the Government. Under questioning from Fraser, Whitlam said on 20 May that the loans pertained to “matters of energy”, that the Loans Council had not been advised, and that it would be advised only “if and when the loan is made.” The following day he told Fraser and Parliament that authority for the plan had been revoked.

A special one-day sitting of the House of Representatives was held on 9 July 1975, during which the Prime Minister tabled the documents containing evidence about the loan and attempted to defend his government’s actions. He did not know that Connor had continued to deal with Khemlani, a fact which was later revealed by Australian newspapers.

Beset by economic difficulties at the time, and by the negative political impact that the ‘loans affair’ conjured up, the Whitlam Government was vulnerable to further assaults on its credibility.

Connor’s authority to seek an overseas loan was withdrawn following leaking of the scandal, but he continued to liaise with Khemlani. A journalist from The (Melbourne) Herald tracked down Khemlani in mid-late 1975 and following an interview, revealed that Khemlani and Connor were still in contact, bringing the ‘loans affair’ to a head. When Connor directly denied Khemlani’s version of events, as reported in The Sydney Morning Herald, Khemlani flew to Australia in October 1975 and provided the Melbourne journalist with a mass of telexes, sent to him from Connor, which refuted Connor’s denial.

On 13 October 1975 Khemlani provided a statutory declaration and a copy of the telexes he had recently exchanged with Connor. He sent copy of the lot to Prime Minister Whitlam. Upon receiving the documents, Whitlam dismissed Connor from his government for misleading Parliament.

In his letter of dismissal, date 14 October 1975, Whitlam wrote: “Yesterday I received from solicitors a copy of a statutory declaration signed by Mr. Khemlani and copies of a number of telex messages between Mr. Khemlani’s office in London and the office of the Minister for Energy. In my judgment these messages did constitute ‘communications of substance’ between the Minister and Mr. Khemlani.”

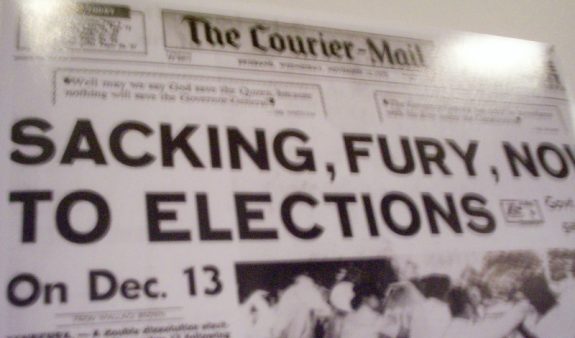

The ‘loans affair’ embarrassed the Whitlam government and exposed it to claims of impropriety. The Malcolm Fraser-led Opposition used its majority in the Senate to block the government’s budget legislation, thereby attempting to force an early general election, citing the ‘loans affair’ as an example of ‘extraordinary and reprehensible’ circumstances.

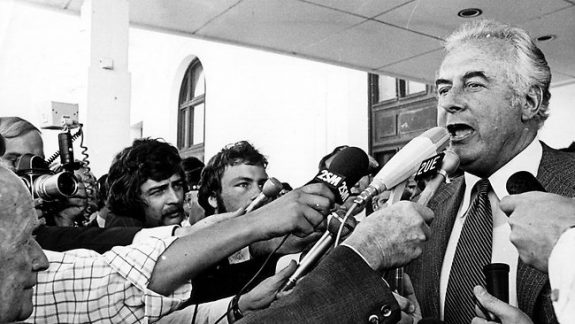

Prime Minister Whitlam refused to call an election. Event precipitated and were concluded by the Royal Ambush of 11 November 1975.

What was not known at the time is that Khemlani had come to Australia several times after the 20 May 1975 revocation of commission for the loan.

He arrived during the crisis which led to the Royal Ambush and was seen carrying two large suitcases. They contained the massive correspondence from and with Connor, and related documents.

It is said that Howard and Phillip Reginald Lynch – later Sir Phillip, then Deputy Leader of the Liberal Party and the future Treasurer in the Fraser Government, spent a night at the Canberra Hotel in Canberra going through the suitcases, and searching for incriminating documents. That is the kind of activity ordinarily confined to ordinary police agents – of all kind. In that way, Howard – nominally a solicitor who should have known better – was trying to earn brownie points with Fraser. Actually, he succeeded beyond expectation: Fraser would appoint him Minister for Business and Consumer Affairs, in charge in particular with the assassination of the Murphy Trade Practices Act 1974.

In government the name of John Howard would be tied to several cases of violation of domestic as well as international law and treaties.

Continued Saturday – The Tampa, Hicks, and Other Cases

Previous instalment – Beyond the ‘Palace Letters’ (part 2)

Dr. Venturino Giorgio Venturini devoted some seventy years to study, practice, teach, write and administer law at different places in four continents.

Dr. Venturino Giorgio Venturini devoted some seventy years to study, practice, teach, write and administer law at different places in four continents.

Like what we do at The AIMN?

You’ll like it even more knowing that your donation will help us to keep up the good fight.

Chuck in a few bucks and see just how far it goes!

Your contribution to help with the running costs of this site will be gratefully accepted.

You can donate through PayPal or credit card via the button below, or donate via bank transfer: BSB: 062500; A/c no: 10495969