‘Parent of the nation’

By Robert Wood

In the national discourse around violence, there seems to be a fetish for land, for resource, for nature. This comes in everywhere from bushfires to mining to farming. It is all about land be that burning or sacred site desecration or settler colonialism in general. That is where we see the common invocation of terra nullius as a guiding principle and a fiction that nevertheless has real world effects. What we know as part of this is that terra nullius is a dangerous myth that justified and reflected the white invasion of the continent. We must remember that. And yet, we must also make another entry in the ledger when we consider violence here. This is the violence done to people, not only country. And so, if terra nullius is something we all know, something that gives rise to the response of land rights and other actions of sovereignty, perhaps we should also learn about parens patriae.

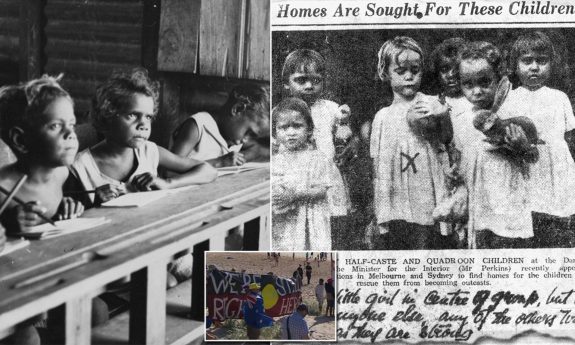

Parens patriae is the doctrine that connects children in foster care to prisoners to mental health detainees. Here violence is not only done to land, but to sovereign individuals. Parens patriae is what justifies how people are treated and it disproportionately affects Aboriginal communities.

But it is not exclusive to them. Terra nullius not only affected Aboriginal people, but also their trading relations with Macassans and others, then we know parens patria impacts on many individuals. You might know this legal concept through the term ‘ward of the state.’ I myself have been a ward of the state. I was institutionalised in 2010, where I spent three blacked out days in a public mental asylum before waking up for another four days of treatment before being released into the community. I was technically, and legally, a ward for a further 23 days. Once committed, this was the minimum time of my sentence before I was allowed my freedom. Thirty days was a short stay and the people I met were very different to my usual set, but I am grateful for the experience. It was humbling to realise my privilege. I was in Locked Room Ward B of Graylands in Perth with homeless white drug addicts in their twenties and Aboriginal Elders from remote communities. I am not white nor Indigenous, and, people like me, people of colour from migrant backgrounds made up the majority of nurses if not doctors.

The lesson I learnt most of all from being inside is that the state is failing in its parental responsibilities. It is failing when we consider parens patriae. Translated from the Latin, this means ‘parent of the nation’ and is often used as a way to recognise the leader of a state, say a monarch or a ruler, or even a dictator like Julius Caesar. It is also the principle that underpins the justification for taking parental responsibility away from traditional custodians and replacing that with institutional forms of authority. My parents committed me and then the West Australian state government became my legal guardian. This was because I was not of sound mind, but you can have your rights taken away for protest, for addiction, for racist reasons. Why does this matter?

Parens patriae matters because it is the logic that allows the state to remove children from their parents, to incarcerate people, to lock people up if their ideas are insane. The response, of course, would be that the state is an adequate parent, maybe even a good one. That Queen Lizzie does a fine job looking after her subjects. It undermines though the responsibilities of individuals, and, as we know from terra nullius, it justifies violence on the pretext that there is no pre-existing expression of care. Quite simply, it attacks the role of parents, especially First Nations people, who are more likely to become wards of the state as children, people in custody, prisoners, mental health detainees, and others who are not free.

Parens patriae is a dangerous fiction that has real effects on real people. It undermines a more complex, diffuse, and co-ordinated network of care, and seeks to make a sole authority replace a parent or a guardian. The pastoralism in communities is often one that permeates to many members and people share the burden when it comes to looking after each other from the vulnerable to the sick to the elderly to the wronged and the accused. What matters for sovereignty is how we re-imagine what our governance can be and how people are looked after when it comes to state treatment of our most vulnerable. That parens patriae continues to be invoked does a disservice to what we are truly capable of.

Robert Wood’s writing has been published in numerous literary and academic journals. He has interned for Overland, edited for Peril and Cordite, been a columnist for Cultural Weekly. At present he works for The Centre for Stories.

Like what we do at The AIMN?

You’ll like it even more knowing that your donation will help us to keep up the good fight.

Chuck in a few bucks and see just how far it goes!