The spying on Timor-Leste case … et cetera (part 1)

By Dr George Venturini

(Much of the material in this page is drawn from the work of La’o Hamutuk, the Timor-Leste Institute for Development Monitoring and Analysis, which has monitored and campaigned for Timor-Leste’s rights for two decades. For more detailed information on this and related issues, see www.laohamutuk.org. Current and updated information on the maritime boundary dispute with Australia is at https://www.laohamutuk.org/Oil/Boundary/18ConcilTreaty.htm).

4. The spying on Timor-Leste case … et cetera

Timor-Leste is a very small country in Southeast Asia: about 15,410 square kilometres; population about 1,2 million; at West, North and East is Indonesia. To the South is Australia.

Once a Portugal colony, the decolonisation process instigated by the 1974 Portuguese revolution moved into a civil war which culminated with independence, unilaterally declared on 28 November 1975. On 7 December 1975 the Indonesian military launched a full-scale invasion of East Timor, having received ‘the green light’ from visiting United States President Gerald Ford and Secretary of State Henry Kissinger the day before. Indonesia’s occupation of East Timor was marked by violence and brutality.

The East Timorese guerrilla force Falintil fought a campaign against the Indonesian forces from 1975 to 1999.

In 1999, following the United Nations-sponsored act of self-determination, Indonesia relinquished control of the territory, and Timor-Leste eventually became the first new sovereign state of the 21st century on 20 May 2002. After independence Timor-Leste became a member of the United Nations and of the Community of Portuguese Language Countries. On 30 August 1999 an overwhelming majority of the people of Timor-Leste had voted for independence from Indonesia. However, in the next three weeks, anti-independence Timorese militias – organised and supported by the Indonesian military – commenced a large-scale, scorched-earth campaign of retribution.

On 20 September 1999 Australian-led peacekeeping troops deployed to the country and brought the violence to an end. In 2006 internal tensions would threaten the new nation’s security when a military strike led to violence and a breakdown of law and order. At Dili’s request, an Australian-led International Stabilisation Force – I.S.F. deployed to Timor-Leste, and the U.N. Security Council established the U.N. Integrated Mission in Timor-Leste – U.N.M.I.T., which included an authorised police presence of over 1,600 personnel. The I.S.F. and U.N.M.I.T. restored stability, allowing for presidential and parliamentary elections in 2007 in a largely peaceful atmosphere. In February 2008 a rebel group staged an unsuccessful attack against the president and prime minister. The ringleader was killed in the attack, and most of the rebels surrendered in April 2008. Since the attack, the government has enjoyed one of its longest periods of post-independence stability, including successful 2012 elections for both the parliament and president. In late 2012 the U.N. Security Council voted to end its peacekeeping mission in Timor-Leste and both the I.S.F. and U.N.M.I.T. departed the country by the end of the year.

“Timor-Leste is blessed – or perhaps condemned – because of large deposits of oil and natural gas under the Timor Sea. The on-shore deposits, including oil and gas seeps which have been collected or flared for over a century, are less-well surveyed and probably smaller than those under the sea, where war did not interfere with oil exploration. Many of the offshore fields are in disputed territory; the following map lists the major known fields which belong to Timor-Leste under current international legal principles.” (Guteriano Nicolau and Charles Scheiner, ‘Oil in Timor-Leste,’ La’o Hamutuk, September 2005).

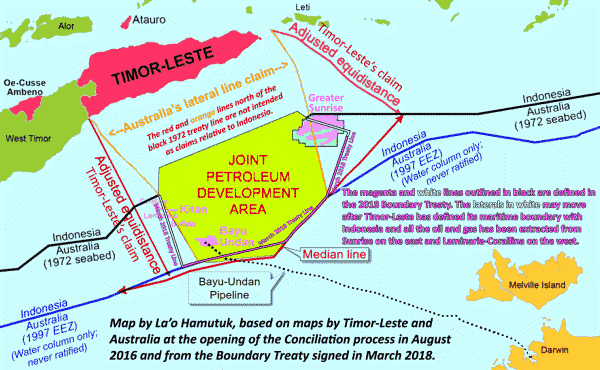

The resources were divided between Indonesia and Australia with the Timor Gap Treaty in 1989. East Timor inherited no permanent maritime boundaries when it attained independence. A provisional agreement, the Timor Sea Treaty, signed when East Timor became independent on 20 May 2002 defined a Joint Petroleum Development Area – J.P.D.A. and awarded 90 per cent of revenues from existing projects in that area to Timor-Leste and 10 per cent to Australia.

The 2002 Timor Sea Treaty was intended as an interim agreement, that is without prejudice to the position of either country on their maritime boundary claims.

The International Unitisation Agreement for Greater Sunrise – I.U.A., signed by Australia and Timor-Leste on 6 March 2003, provided the secure legal and regulatory environment required for the development of the Greater Sunrise gas reservoirs. Under the Timor Sea Treaty, Greater Sunrise was apportioned on the basis that 20.1 per cent would fall within the J.P.D.A. and the remaining 79.9 per cent would fall in an area to the east of the J.P.D.A. in which Australia regulates activities in relation to the resources of the seabed and subsoil.

The Certain Maritime Arrangements in the Timor Sea – C.M.A.T.S. Treaty, signed on 12 January 2006, embodied a further interim agreement, that is without prejudice to the position of either country on their maritime boundary claims. The principal aim of the treaty was to allow the exploitation of the Greater Sunrise gas reservoirs to proceed while suspending maritime boundary claims for a significant period and maintaining the other treaty arrangements in place. Australia and Timor-Leste brought the 2003 I.U.A. and the 2006 C.M.A.T.S. Treaty into force on 23 February 2007.

The Greater Sunrise project was intended as a transfer of revenue to Timor-Leste of as much as US$ 4 billion over the life of the project. The exact benefit to Timor-Leste and Australia would depend on the economics of the project. Both Australia and Timor-Leste were bound by the Treaty to refrain from asserting or pursuing their claims to rights, jurisdiction or maritime boundaries, in relation to the other, for fifty years. The two countries undertook not to commence any dispute settlement proceedings against the other which would raise the delimitation of maritime boundaries in the Timor Sea.

The Australian Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade offers the following view of the respective position of the two countries:

The Timor-Leste Petroleum Fund was established in 2005, and by 2011 it had reached a worth of US$ 8.7 billion. Timor-Leste is labelled by the International Monetary Fund as the “most oil-dependent economy in the world.”

A 2005 agreement between Timor-Leste and Australia mandated that both countries put aside their dispute over maritime boundaries and that Timor-Leste would receive fifty per cent of the revenues from the resource exploitation in the area – estimated at AUS$ 26 billion over the lifetime of the project – from the Greater Sunrise development.

The Greater Sunrise Project is a pair of good-sized gas and condensate fields – the Sunrise and Troubadour.

The Sunrise partners, led by operator Woodside – which owns 33.44 per cent of the project – along with ConocoPhillips – with 30 per cent, Shell – with 26.6 per cent and Osaka Gas – 10 per cent, were prepared to spend the billions necessary to extract and process the gas wealth. But Sunrise became mired in a sink of misplaced aspirations and misunderstanding born of good intentions and an understandable national guilt. The Sunrise and Troubadour discoveries sit at the northern edge of Australia’s continental shelf, some 450 kilometres northwest of Darwin but about 150 kilometres southeast of Timor-Leste, in water depths from 100 metres to more than 600 metres in the Bonaparte Basin. The Greater Sunrise contracts between Woodside plus its joint venture partners and the governments of Timor-Leste and Australia were signed in 2003, replacing contracts with Australia and Indonesia during the illegal Indonesian occupation.

Woodside Petroleum Limited calls itself Australia’s largest independent oil and gas company. It is, in fact, much more than that.

Joining the medium-sized Burmah Oil, which had started in Assam and Burma during the British Raj, and Anglo-Dutch Shell, had been a small Australian exploration company named Woodside. Originally incorporated under the name of Lakes Entrance, a small town in Gippsland near the Bass Strait oil fields, the site of its first exploration, Woodside had since turned its attention to Australia’s north-western waters.

The Australian Government never made it clear that its view of the boundary between Australia and Timor-Leste was subject to a claim to the seabed which extended to the southern edge of the so-called Timor Trough, a valley 3,000 metres deep in the sea generally 100 to 600 metres deep. The argument was based on the alleged weight of geological opinion that this trench, much closer to the Timor coast than to that of Australia, marked the limit of the Australian continental plate.

This view certainly favoured Woodside.

Today Woodside Energy is Australia’s largest publicly traded oil and gas exploration and production company and one of the country’s most successful explorers, developers and producers of oil and gas.

Its registered office is in Perth, Western Australia; its operation, around the world.

Until August 2017 the chairman of the board of directors belonged to one of the ‘Establishment’ families in Western Australia. He had been for 22 years to 2005 managing director of Wesfarmers Limited, one of the largest Australian conglomerates, one of Australia’s largest retailers and, with more than 200,000 employees across the country, the largest private employer in Australia. Woodside’s chairman moved to the petroleum industry as a geologist working on the North West Shelf, in Indonesia and in the United States. He was almost concurrently a non-executive director of BHP Billiton Limited from 1995 to 2005, and of BHP Billiton Plc between 2001 and 2005, chair first and then director of a huge company which provides financial advisory and fund management services through its subsidiaries, including leveraged private equity transactions and buy-outs and property investment management services. BHP Billiton Limited and BHP Billiton Plc were renamed BHP Group Limited and BHP Group Plc, respectively, on 19 November 2018.

BHP is an Anglo-Australian multinational mining and petroleum company headquartered in Melbourne, Australia – largely the receptacle for Anglo-American’s former apartheid money!

It is the world’s largest mining company measured by revenues and the world’s third largest company measured by market capitalisation.

It is one of the behemoths to which every Australian government up to 1972, and since the Royal Ambush coup of November 1975 which dispensed of the Whitlam government, must pay homage – promptly and seriously!

The Whitlam Government had other ideas as to what to do with the North-West Shelf and its utilisation in the interest of all Australians.

The project had become the obsession of the Minister for Minerals and Energy, Reginald Francis Xavier ‘Rex’ Connor. Connor wanted to develop an Australian-controlled mining and energy sector, one not controlled by the mining companies. Among his plans were a national energy grid and a gas pipe-line across Australia from the North-West Shelf gas fields to the cities of the south-east.

Connor’s economic nationalism was popular with the Labor rank-and-file, and the 1973 oil crisis seemed to many to be a vindication of his views. But the flood of petrodollars which accompanied the energy crisis proved to be Connor’s undoing.

What followed is commonly referred to as the ‘Khemlani loans affair,’ already dealt with.

Of course, by the time freshly shaped neo-liberal Labor returned to office in 1983, Connor’s economic nationalism and dreams of massive state investment in energy projects would be totally rejected.

The North-West Shelf gas field’s development would be given to Woodside.

Woodside’s former chairman was also chairman of National Australia Bank Limited, one of the four Australian banks – which form a veritable cartel, between 2005 and 2015; a member of the J.P. Morgan International Council and, to top it all and to show a respectable connection with ‘academia’, chancellor of the University of Western Australia between 2005 and 2017. A directorship of the Centre for Independent Studies, a solidly right-wing think-tank, completes the ‘colour’ and qualification for ‘the Establishment’. Woodside would in time extend its hospitality to former Foreign Minister of the Howard government upon his retirement. Mr. Alexander Downer would be welcomed in an advisory capacity, quite ‘properly’ offered through the services of Bespoke Approach an Australian corporate advisory firm and registered political lobbyist of Downer’s making. Mr. Downer’s successor, Martin Ferguson, Minister for Energy of the Labor Government would, on losing his position at the federal election of 2013, moved quickly, eagerly and directly to the position of member of the board of Woodside. And that is reward for talent!

But for an example of ‘flexibility’ it is hard to beat Mr. Gary Grey, National Organiser (1986-1993) and National Secretary of the Labor Party(1993-1999), then Executive Director of Wesfarmers (2000-2001), ‘principal strategic adviser’ and then Director of Corporate Affairs with Woodside (2001-2007) until he was elected with Prime Minister Kevin Rudd in 2007, appointed Parliamentary Secretary to the Minister for Infrastructure with Responsibility for Northern and Regional Australia in the First Rudd Ministry. He later moved to Prime Minister Julia Gillard who chose him as Special Minister of State (located in the Department of Finance and Deregulation) and Special Minister of State for the Public Service and Integrity in the Second Gillard Ministry and later Minister for Resources and Energy, the Minister for Tourism and the Minister for Small Business. Oh, for the polyvalence of the neo-Laborals!

The C.M.A.T.S. Treaty was signed by Foreign Ministers Alexander Downer and José Ramos-Horta in Sydney on 12 January 2006, in the presence of Prime Ministers John Howard and Mari Alkatiri.

Timor-Leste ratified both C.M.A.T.S. and the International Unitisation Agreement for the Sunrise and Troubadour fields separately on 20 February 2007, publishing the Parliamentary Resolutions on 8 March in the Official Gazette in Portuguese.

The C.M.A.T.S., the product of eight years of negotiation, had advantages and disadvantages for both countries. In summary, Timor-Leste increased its share of upstream revenues from 18 per cent to 50 per cent in return for accepting Australian sovereignty over areas east and west of the J.P.D.A., ratifying the I.U.A., and agreeing not to raise the maritime boundary question for 50 years. Many people in Timor-Leste expressed the view – and alarm – that the balance was not in Timor-Leste’s favour. They continued to believe that Timor-Leste has the right to all maritime and seabed resources in the Exclusive Economic Zone. The signatories and oil companies concerned had hoped that C.M.A.T.S. and the I.U.A. would open the way for Greater Sunrise to be exploited. The basic development plan for the project was still not settled by late 2012, with Timor-Leste holding out for a pipeline to an liquefied natural gas plant in Beacu on Timor-Leste’s south coast, and the Sunrise Joint Venture – led by Woodside, with Shell, ConocoPhillips and Osaka Gas – preferring a mid-sea floating plant.

Continued Wednesday – The spying on Timor-Leste case … et cetera (part 2)

Previous instalment – The Dr Mohamed Haneef case

Dr. Venturino Giorgio Venturini devoted some seventy years to study, practice, teach, write and administer law at different places in four continents.

Dr. Venturino Giorgio Venturini devoted some seventy years to study, practice, teach, write and administer law at different places in four continents.

Like what we do at The AIMN?

You’ll like it even more knowing that your donation will help us to keep up the good fight.

Chuck in a few bucks and see just how far it goes!

Your contribution to help with the running costs of this site will be gratefully accepted.

You can donate through PayPal or credit card via the button below, or donate via bank transfer: BSB: 062500; A/c no: 10495969

2 comments

Login here Register here-

Lambchop Simnel

-

Return to home pageDr Venturini usually sends me away for some thought.

With this issue one of the few journalist to have dealt with this sort of issue is Lenore Taylor, who a few years ago reminded us of how many $ our corrupt politicians had let go in, following petro company ideas on how the Gap should be managed and by whom. More later, when necessary.

Given the strange ideas one or two people have about Dr Venturini, I thought I would include the following:

Pingback: The spying on Timor-Leste case ... et cetera (part 2) - » The Australian Independent Media Network