The market won’t save the world

There is no doubt amongst conservatives that the market system is the best way to create wealth by encouraging everyone to look out for their own best interests.

But the market system was not designed to share wealth, to support the vulnerable, or to protect the environment. The market does not recognise intrinsic worth but rather views everything and everyone as a commodity judged by its productive capacity.

So, as it stands, the market system enriches the wealthy, impoverishes the poor, and endangers the planet.

In last autumn’s essay, Evangelii Gaudium, Pope Francis wrote that:

“Just as the commandment ‘Thou shalt not kill’ sets a clear limit in order to safeguard the value of human life, today we also have to say ‘Thou shalt not’ to an economy of exclusion and inequality. Such an economy kills … Today everything comes under the laws of competition and the survival of the fittest, where the powerful feed upon the powerless. As a consequence, masses of people find themselves excluded and marginalised: without work, without possibilities, without any means of escape. Human beings are themselves considered consumer goods to be used and then discarded.”

Rightwing politicians argue that overcoming inequality robs the rich of incentives to invest and the poor of incentives to work and is counter-productive, but there is an increasing body of evidence challenging this view.

Last year the IMF, which advises governments on sustainable growth, released a discussion paper which found that countries with high levels of inequality suffered lower growth than nations that distributed incomes more evenly. Further, an analysis of various efforts to redistribute incomes showed they had a neutral effect on GDP growth.

Lifting people out of poverty, improving their health and education, and increasing their buying power, has a positive economic benefit that outweighs any small negative from the rich having a slightly smaller share of the pie.

“Rather than a trade-off, the average result across the sample is a win-win situation, in which redistribution has an overall pro-growth effect, counting both potential negative direct effects and positive effects of the resulting lower inequality,” they said.

It warned that inequality can also make growth more volatile and create the unstable conditions for a sudden slowdown in GDP growth.

The World Bank Group announced twin goals of ending poverty by 2030 and promoting shared prosperity.

The first goal is to essentially end extreme poverty, by reducing the share of people living on less than $1.25 a day to less than 3 per cent of the global population by 2030. The second goal is to promote shared prosperity by improving the living standards of the bottom 40 per cent of the population in every country.

Three key elements are considered to be of particular importance: greater investment in human capital, judicious use of safety nets, and steps to ensure the environmental sustainability of development.

In the past few decades, substantial progress has been made in reducing global poverty. Between 1990 and 2011, the number of people living in extreme poverty has halved, to around one billion people, or 14.5 per cent of the world’s population.

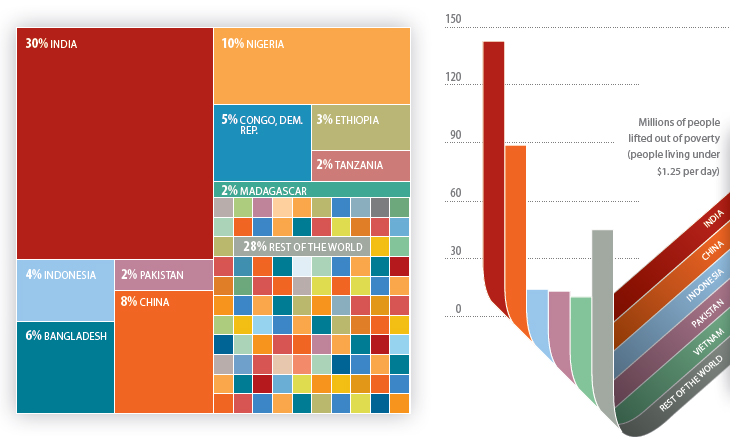

According to the 2011 estimates, almost three-fifths of the world’s extreme poor are concentrated in just five countries: Bangladesh, China, the Democratic Republic of Congo, India, and Nigeria. Adding another five countries (Ethiopia, Indonesia, Pakistan, Madagascar, and Tanzania) would encompass just over 70 per cent of the extreme poor.

Percentage of people living in extreme poverty:

The world’s most populous countries, China and India have played a central role in the global reduction of poverty as measured by the $1.25 poverty line. Together they lifted some 232 million people out of poverty from 2008 to 2011

In many low- and lower middle-income countries, there is significant overlap between those living in absolute poverty and the bottom 40 per cent of the population. In 26 countries the number of people living in extreme poverty is equal to or more than 40 per cent of the population in 2011. These countries account for about a quarter of the world’s extremely poor people.

All these countries except Haiti and Bangladesh are in Sub-Saharan Africa, and all except for Bangladesh, the Democratic Republic of Congo, Nigeria, and Tanzania have a population of less than 30 million people. Therefore, their high poverty rates do not make a significant contribution to the total number of the extremely poor at the global level. Nevertheless, reducing poverty in these countries is a moral imperative and as important as poverty reduction in any other country.

Many poor people may become “trapped” in poverty because of failures in credit, land, or other key markets, governance failures, or because low levels of education, skills, or health prevent them from availing themselves of new opportunities arising from a general expansion of economic activity. The remaining poor may be in hard-to-reach pockets of the population, for example because they live far from centres of economic activity or because they suffer exclusion due to ethnicity or language. Also, many poor people live in countries experiencing conflict, which may not participate in any global expansion of economic activity.

The economic benefit, and moral obligation, of lifting people out of poverty is inextricably linked with so many other global problems.

Overpopulation must be addressed. It has been shown that educating and empowering women has a significant effect on reducing the size of families. Also we need proper resourcing of voluntary family planning services, which still receive less than one per cent of world aid for reproductive health, and the removal through education and the media of the many barriers that continue to stop millions of women from having the choice to access methods of contraception.

Religions have a role to play here and should reconsider their opposition to many practices such as contraception, abortion, euthanasia, same-sex marriage and divorce. Procreation should not be the considered the inevitable purpose of relationships.

The OECD identifies climate change as a serious risk to poverty reduction which threatens to undo decades of development efforts. As the Johannesburg Declaration on Sustainable Development states, “the adverse effects of climate change are already evident, natural disasters are more frequent and more devastating and developing countries more vulnerable.” While climate change is a global phenomenon, its negative impacts are more severely felt by poor people and poor countries.

The economic importance of climate-sensitive sectors (for example, agriculture and fisheries) for these countries, and their limited human, institutional, and financial capacity to anticipate and respond to the direct and indirect effects of climate change, makes developing countries more susceptible. The countries with the fewest resources are likely to bear the greatest burden of climate change in terms of loss of life and relative effect on investment and the economy.

Climate change will further reduce access to drinking water, negatively affect the health of poor people, and will pose a real threat to food security in many countries in Africa, Asia, and Latin America. In some areas where livelihood choices are limited, decreasing crop yields threaten famines, or where loss of landmass in coastal areas is anticipated, migration might be the only solution.

Increasingly, poverty and the destruction of land through climate change, natural disasters or conflict will add to the tsunami of displaced people around the world. To denigrate someone as an “economic migrant” seems churlish when their alternative is starvation.

As we face increasing competition for food, water and dwindling resources, conflict seems inevitable unless we can all accept that we must be part of the solution.

Every individual must try to reduce their environmental footprint.

We must put aside our greed and demand that we increase foreign aid and take urgent action to mitigate climate change.

Governments must recognise their responsibilities as global citizens and regulate and legislate to protect us against the voracious quest for profit at any cost that the market encourages. They also have a moral obligation to more fairly share the world’s wealth and resources.

‘We have not inherited the earth from our grandparents, we have borrowed it from our grandchildren.’

Like what we do at The AIMN?

You’ll like it even more knowing that your donation will help us to keep up the good fight.

Chuck in a few bucks and see just how far it goes!

Your contribution to help with the running costs of this site will be gratefully accepted.

You can donate through PayPal or credit card via the button below, or donate via bank transfer: BSB: 062500; A/c no: 10495969