On 1 October, the Affordable Health Care Act comes into force in the United States. It has split the US down the middle – by some polls, over half of the population hates the Act. Detractors call it “Obamacare” as if to identify it with a single person is to devalue the raft of policy and the nation-changing effects it will have. Republicans, quite simply, hate it outright.

I recently requested clarification from a right-wing, evangelical Christian blog as to why, if the Act is of so much benefit to the poor and downtrodden of America, the right oppose it.

I received in response a bullet list of seven reasons “Obamacare” is a disaster for America. Of these seven objections, one is a moral statement: the argument that some aspects of the law don’t suit all people, but will apply to all people. The argument was made that funding for abortions may be made available through the Act. This is highly arguable, at least in the law as enacted, but fair enough; this seems like a valid objection.

It is entirely legitimate to oppose legislation on the basis of disagreement with the moral outcomes. Two of the objections question the effectiveness of the legislation. Similar to the Australian Coalition flatly stating that Labor, even when in possession of a good idea, cannot turn it into effective action, opponents of the AHCA point to other countries with national healthcare systems and claim that they’re not perfect.

They argue that such systems will be open to abuse, rorting and fraud. You could argue that all systems are open to abuse, rorting and fraud and that this is a good reason to refine the legislation to progressively remove these opportunities; however, it’s not an entirely invalid objection.

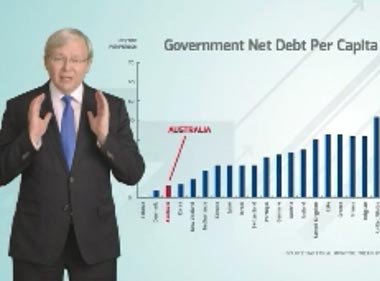

And three of the objections boil down to the basic assertion: “We can’t afford it”. The policy will cost the US government, and thus the taxpayer. The US is already debt-ridden. The government ought to concentrate on paying down debt before engaging in further expenditure. Fair enough. That does seem a valid, and eerily familiar, objection. Except…

“We can’t afford it” has become a catch-cry of conservatives the world over. The Affordable Healthcare Act? Can’t afford it. National Broadband Network? Can’t afford it. Public servants? Can’t afford them. Social support and welfare? Can’t afford them.

Government is a case of competing priorities. All governments work within limitations of resources, in terms of finance and political goodwill and legislative time and personnel; every potential advance in society which government needs to enact comes at the expense of other needs. To evaluate whether “can’t afford it” is ever a valid objection to policy advances, let us take a step back and examine what it is that we have a government for.

The human species is gregarious by nature. Since the formation of the first agrarian communities, we have instituted some kind of authority structure. All governments throughout history have entailed a personage, or group of personages, to which the people voluntarily surrender power and authority. The people sacrifice their autonomy, their time, and their taxes, for the sake of the benefit of the whole.

For many centuries, the fundamental purpose of government was law and order, and peace/protection from invasion. In other words, government’s areas of responsibility went no further than setting the legislature and maintaining a standing army which, in addition to its function of protecting the people against hostility from outside, also enforced the law.

Some empires also dabbled in infrastructure. The ancient empire of Rome is famous for its network of roads; after the fall of the Roman empire, significant expenditure on roads would not be seen again in Europe until the 1800s. Rome also built aqueducts to service its wealthy citizens. The Roman empire was centuries ahead of its time, but in modern society, we expect governments to spend some resources on infrastructure. Roads, water, sewerage, power, telecommunications – these things that modern society relies upon are part of the bread and butter of modern government.

Governments of old, however progressive in their approach to infrastructure and law and defense, had no interest in some of the areas we currently consider to be expected parts of civilisation. Rome implemented a “corn dole” for citizens too poor to buy food; the Song dynasty in China (circa 1000 AD) managed a range of progressive welfare programs. Apart from a few stand-out examples such as these, however, social support was nonexistent.

Modern-day welfare came into being in the 19th and 20th centuries. We now consider a certain level of unemployment benefit, disability benefit, aged care benefit, etc. to be a reasonable imposition on society. Before the 1900s, the unemployed and the aged (and unmarried women) were the responsibility of their families, not of society as a whole.

It wasn’t until the 1700s that history saw the first public, secular hospitals being created. Prior to this, health care would have been taken care of by organisations other than government; primarily, in Europe, by the Church and the monasteries. Education is a similar story. Before the emergence of universal education for the populace – as early as the 1700s in some parts of Europe, but not widespread until the 19th century AD – education was reserved for the elite and provided by the churches.

It is important to note that for all of this time, the churches and other bodies responsible for providing these services – education, health care, welfare – were accepted and fundamental parts of society, and society contributed to them regularly and generously. Everybody gave alms to the churches. The monasteries were at the center of landholdings in their own rights and levied taxes upon their surrounds. In a way, these organisations were analogous to government – they received support from society as a whole, and in return, they provided certain necessary services.

In the modern world, the social bodies that would have been responsible for education and healthcare are declining or have died. Catholic schools and hospitals still exist, but not to the extent required to support our population. For the past 200 years governments have taken on these responsibilities, as the world gave way to secular sympathies, and governments took on these responsibilities as key determinants of national progress and success. A healthy, educated populace was the key to national prosperity.

Which brings us to the present. In 2013 we have conservative groups and political parties wanting the government to get out of the way while the market takes care of these things. On infrastructure – for example, the NBN – let it be driven by market forces. Environmental action, likewise: rather than a carbon tax operated by the government, a “direct action” policy will find the emissions abatements efforts that already exist and support them, rather than mandating change from the outside.

We have Republicans and Liberals wanting the government to get out of the business of mandating healthcare because it ought to be driven by market forces. We have governments of all persuasions pursuing privatisation and outsourcing of previously fundamental responsibilities in the name of efficiency and cost-effectiveness. And we have governments preferring to return the community its taxes in the form of tax cuts (to individuals; to business) and infrastructure spending. All of this comes with a wave of the hand and a “we can’t afford [whatever]”.

But can the government really abrogate its responsibilities in these areas? Without other bodies or structures to take on these responsibilities, it’s not ethical to stop providing them. So can the free market be relied upon to do this?

Money to pay for education, fire services, health, broadband, has to come from somewhere. The social structures – primarily church – which previously might have supported these things no longer have the resources or the popular support to be able to take up the slack. Charities around the country are crying out for support and berating the government for not providing enough basic resources/support; something has to give. In this environment, the idea of “small government” doesn’t make sense.

The government has to be big enough to do the things that the monasteries aren’t around to do anymore.

The Republican right in the US and the Lib-Nats in Australia run on a platform of “individual empowerment”. With the exception of a few big-ticket items, where they have specific, active policies – policies towards boat people come to mind – the Coalition’s ideology is to get out of the way, reduce government’s interference in society, reduce the tax burden on individuals and corporations, and let the free market have its way. It believes that everyone will benefit if there are lower taxes and more money moving.

Let’s put aside for a moment the fact that trickle-down economics doesn’t work. Even in some fictional world where successful humans were altruistic enough to plough their profits back into providing more employment and more productivity, rather than squirreling away the proceeds as profit, we still need these other functions to happen.

And these other functions – hospitals, schools, heavy rail, telecommunications infrastructure – don’t happen at the behest of successful capitalists. They happen because the community needs them and the community as a whole will pay for them.

Individualism is what you have when you don’t have strong governments. Individual empowerment is what you get when the strong ride roughshod over the weak.

Now we seem to be on the verge of voting in a Coalition government which will be forced to cut back on all sorts of areas of service provision and expenditure if it is to meet its overriding goal of bringing the budget back to surplus.

A government whose budget figures and estimates we’ve not been allowed to see, which is promising to repeal several sources of revenue and increase expenditure in several areas, whilst not increasing taxes. Something has to give. It seems certain that “We can’t afford it” will come into force after the election in a big way.

“We can’t afford that” is never a valid excuse. That’s what government is for: to find a way to be able to afford the basic things we need our government for. If that involves raising taxes in an equitable manner, then that’s what you do – it’s exactly why we pay taxes in the first place.

If it involves an imposition on businesses to achieve an end that the community desires – for example, a carbon tax – then that is why we have a government. The whole purpose of government is to place impositions on the strong to benefit the weak and to regulate the individual to offer benefits to the whole.

A government that doesn’t want to do these things is not governing.

A government that doesn’t want to provide these things is a government that doesn’t want to govern.

Like what we do at The AIMN?

You’ll like it even more knowing that your donation will help us to keep up the good fight.

Chuck in a few bucks and see just how far it goes!

Your contribution to help with the running costs of this site will be gratefully accepted.

You can donate through PayPal or credit card via the button below, or donate via bank transfer: BSB: 062500; A/c no: 10495969