Violence in our churches

We must always condemn violence. There must be no tolerance for brutality, and we must take action to diminish violence whether it is tied to family violence, a chronic lack of support for crucial mental health work or to sectarianism. The stabbing of Bishop Mar Mari Emmanuel on the weekend during his church service, days after the Bondi stabbing, demands Australia focuses on solving the causes.

The youth in question has now been charged with a terror offence after a rapid declaration that the incident was terror-related. As commentators have pointed out, however, this designation is controversial. Dai Le MP, whose electorate this involved, condemned the choice of the terror label, explaining it would inflate community anxiety.

The deployment of 400 police to seize his teenage friends, with more terror charges laid, seems another case of police overkill, and not destined to calm the current sense in Muslim communities that the West sees their lives as either worthless or an implicit threat. In a moment of youth mental health crisis, it is hardly helpful to inflict night-time raids.

Notably the placing of a bomb-like object at a Sydney property flying a Palestinian flag has not been treated the same way, despite the terror the threat provoked. The Australian Federation of Islamic Councils noted the lacklustre police response to this and similar incidents. Repeated attacks on the properties of Hash Tayeh, owner of the Burgertory chain, do not receive the terror hysteria.

Bernard Keane underlines that the terror label gives police draconian powers as well as functioning as a “security blanket” that protects us from the apparent arbitrariness of violence. So-called “terror” attacks, he points out, are just as likely to relate to mental health issues.

Violence against women is also systematically connected to “terror” attacks, where there is misogyny and often an unchecked history of violence against women in men found guilty of terrorist violence. Kon Karapanagiotidis highlighted that the total number of Australians killed in terror attacks here since World War I is 16, while 642 women have been killed by male violence merely since 2014. Misogyny, as he reiterates, should be counted a much higher threat and a focus for action, not only because of its link to terror but also for the wellbeing of women.

There is an obvious reason, as Muslim community organisations have pointed out, that the attack on the Bishop was so rapidly labelled terror rather than a hate crime. Australians have a deep underlying predisposition to see Muslims and non-White people as terrorists, while our own contenders for the label are excused. It explains the electorate’s complicity with human rights-abusing treatment of our asylum seeker population over recent decades.

This predisposition underpins Prime Minister Albanese offering the “bollard” hero citizenship but neglecting the brave intervention of the two Muslim security guards in Bondi, one of whom gave his life. This refugee had come to Australia for safety and died just a year later trying to save others. It explains why Peter Dutton applauded offering “bollard man” citizenship for a display of the “Anzac spirit,” but said the response to the security guards must be “an issue for the PM.”

Andrew Hastie’s response to the two stabbings was even more illuminating. He demanded stronger national security steps from Prime Minister Albanese, because of the “strategic disorder we’re seeing in the Middle East,” reiterating his words from the “Securing our Future” National Security Conference at the ANU on the 10th of April. Hastie’s SAS time in Afghanistan or his Evangelical Christianity might feed in to this triggering of the “national security” trope, tying a deeply troubled teen to violence in the Middle East.

Hastie’s Christianity provokes him to oppose LGBTQIA+ equality. He famously delivered a “stinging rebuke” to Cooper’s brewery when it backed away from a controversial video where Hastie declared his rejection of marriage equality. While he insists on the separation of church and state, he echoes the American Christian Nationalist assertion that this is intended to keep the state out of interfering in matters of church (not the reverse). He also claims that the “Christian voice” must not be marginalised in Australia’s democracy.

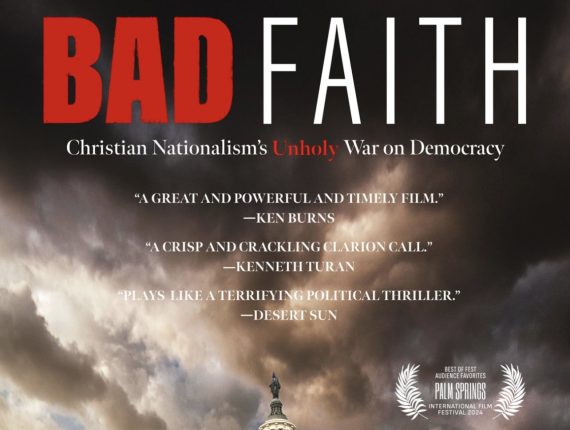

The development of Christian Nationalism has been a concerted project strategised over decades in America and fostered globally in allied religio-ethnostate politics. The dark money that went into manufacturing islamophobia serves Israeli, Hindu, Buddhist and Christian Nationalists. The bigotry is accompanied by repressive morality.

The ex-communicated Bishop’s point of view is overtly in line with Christian Nationalist sentiments. LGBTQIA+ people, Emmanuel has stated, are not just sinners like the rest of us but that they commit “a crime in the sight of God.” In rejecting the Lord’s designated sex designation they commit, “the abolishment of human’s identity.” He appears to say that “LGBT” people, while he loves and prays for them, have rejected their humanity: “The moment you come out of that human identity, you are no longer in that human cycle.” In America, the dehumanising of LGBTQIA+ people is central to the project aiming to staff Trump’s administration.

The Bishop clearly identifies with the American Christian Nationalist movement that surrounds Donald Trump whom he states to be chosen by the Lord. In fact, he claims the Lord says a failure to reelect Trump in November will mean “you can kiss America goodbye,” and that “Christians will be persecuted beyond measure” if he is not elected.

After his imagined meeting with the reinstalled President Trump, the Bishop intends to fix Australia. Emmanuel will “sack everyone in the Parliament House,” and that “whoever comes with a suit, I’ll sack them.”

The people he says will run the country? “So all those big boys with muscles and tattoos, you’ll be the next ministers. The new Cabinet.”

This is deeply disturbing, even if it is meant as a joke. The excommunicated Bishop is apparently a much loved and unifying figure amongst the diaspora Christian communities who have found safe haven in Australia from persecution in the Middle East. This includes Middle Eastern Catholic, Maronite, and Coptic Christians as well as Assyrian. The Sydney Morning Herald conveyed how triggering the stabbing was to a network of communities whose sense of safety is fragile.

During the World Pride event hosted in Sydney in 2023, however, gangs of young men prominently featuring Maronite Christians were on the streets intimidating LGBTQIA+ festival goers, spitting in their faces, calling it “prayer.” Were these inspired by the “TikTok Bishop”?

It is not only LGBTQIA+ people who might be endangered by the renegade Bishop’s sermons. He also appears to spread misogyny. The UN he depicts as the “great harlot who corrupted the earth with her fornication.” In discussing technology, he expresses his shock at the women in entertainment who appear “fully not covered.” Apparently uncovered women “destroyed” the “human way of thinking.” It is evil, and little children “are no longer innocent” from seeing this material on social media.

The Bishop is a complicated man. Apparently he does much good but he also expresses his bigotry in his “humorous” caricatures of, for example, Koreans, as part of geopolitical fearmongering. He dismissed Islam in “many of his sermons.” The religious ethnostate and militarism are central to this Christian Nationalist worldview.

We must discuss the elements of Christian Nationalism that promote violence, whether in its demonisation of Islam and LGBTQIA+ people, or its inculcation of the misogyny that is connected to so much violence in our society.

There is no excuse for this stabbing. We must work to address the many causes, including heated rhetoric, that promote it.

A briefer version of this essay was first published in Pearls and Irritations as “The Bishop.”

Like what we do at The AIMN?

You’ll like it even more knowing that your donation will help us to keep up the good fight.

Chuck in a few bucks and see just how far it goes!

Your contribution to help with the running costs of this site will be gratefully accepted.

You can donate through PayPal or credit card via the button below, or donate via bank transfer: BSB: 062500; A/c no: 10495969