The spying on Timor-Leste case … et cetera (part 5)

By Dr George Venturini

(Much of the material in this page is drawn from the work of La’o Hamutuk, the Timor-Leste Institute for Development Monitoring and Analysis, which has monitored and campaigned for Timor-Leste’s rights for two decades. For more detailed information on this and related issues, see www.laohamutuk.org. Current and updated information on the maritime boundary dispute with Australia is at https://www.laohamutuk.org/Oil/Boundary/18ConcilTreaty.htm).

It has been calculated that, since 1999 and up to the end of 2015, Australia has received nearly US$5 billion in government revenue from oil and gas fields in Timor-Leste’s territory from Laminaria-Corallina, Kitan, Bayu-Undan and Elang-Kakatua. During the same period, Australia provided military aid – through Interfet (International Force in East Timor) and I.S.F. (International Stabilisation Force) – costing US$0.6 billion, and another US$1 billion in ‘bilateral assistance’. Timor-Leste has thus given Australia more than US$3 billion.

On 27 November Hamish McDonald criticised Timor-Leste’s strategy on boundaries and the Tasi Mane project, expanding on a similar article he wrote for Nikkei Asian Review the previous week. (The Saturday Paper, 27 November 2015).

The Lateline news programme on A.B.C. television covered the spying scandal in three in-depth reports on 25-27 November, including interviews with Timorese leaders and Bernard Collaery, former advisor Peter Galbraith, attorney Nicholas Cowdrey and Senator Nick Xenophon. (A.B.C., Australia-East Timor spying scandal: senior lawyer says ‘crime was committed’, 26 November 2015). Following this extended exposure of alleged illegal activity by Australian officials and intelligence agents, Senator Xenophon called for a royal commission and Crikey.com dubbed the lack of accountability “an international embarrassment.” (‘We need to hold East Timor spies to account’, Crikey, 26 November 2015) However, when Senator Xenophon and Greens Senator Scott Ludlam tried to have the Senate resolve to return Witness K’s passport, the government blocked it. (S. Ludlam, ‘Government denies justice to East Timor’, Media release, 1 December 2015).

Planning Minister Xanana Gusmão reiterated Timor-Leste’s position when he received an honorary doctorate from Melbourne University on 7 December, 40 years after Indonesian invaded Timor-Leste with Australian diplomatic support: “The Government of Timor-Leste has made the permanent delimitation of maritime boundaries a national priority as it is the final step in our long struggle for full sovereignty.

Indonesia and Timor-Leste have commenced maritime boundary negotiations and have agreed to abide by the principles set out in the 1982 United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea and international law. Australia on the other hand has refused to negotiate a maritime boundary with Timor-Leste and Timor-Leste cannot refer the issue to be determined by an independent umpire. This is because in 2002, on the eve of Timor-Leste’s independence, Australia withdrew from the compulsory dispute mechanisms set up under the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea for any disputes relating to the delimitation of its maritime zones.

Like your new Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull, I am an optimist. And so, I look to the new Australian Government to recognise that it is in Australia’s national interest to have a clearly defined permanent maritime boundary in the Timor Sea. From the Timorese perspective we are fighting for justice in the Timor Sea so that we can finish the work of our struggle for independence and achieve our rightful sovereignty under international law. We are continuing to be idealists.” (Democratic Republic of Timor-Leste, Acceptance speech on the award of an honorary Doctorate of Letters from the University of Melbourne by His Excellency, the Minister for Planning and Strategic Investment and former President and Prime Minister of the Democratic Republic of Timor-Leste Kay Rala Xanana Gusmão, Melbourne, 7 December 2015).

On 8 December the Australia Timor-Leste Business Council reported on their meeting the previous day with Australian ambassador to Timor-Leste Peter Doyle, whom they had asked to reduce sovereign risk by agreeing to a permanent maritime boundary. Their press release prompted comments from Asia Pacific Analysis (‘Regarding talks between East Timor and Australia’, 11 December 2015).

On 1 March 2016 The Sydney Morning Herald reported that Australian Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull had rejected Timor-Leste P.M. Rui Araujo’s request to begin maritime boundary negotiations, although Turnbull did agree to continue discussions. (T. Allard, ‘P M Malcolm Turnbull disappoints East Timor on talks on maritime boundary’, 1 March 2016).

On 4 April Timor-Leste’s Parliament unanimously resolved to support the negotiation process for maritime boundaries. (RDTL National Parliament, Draft Resolution n. 26 / III (4), Support for the negotiation process for the maritime boundaries of Timor-Leste, 4 April 2016).

On 11 April Timor-Leste announced that it had just notified Australia that it was initiating “compulsory conciliation proceedings under the U.N. Convention on the Law of the Sea, U.N.C.L.O.S., with the aim of concluding an agreement with Australia on permanent maritime boundaries.” (‘Timor-Leste launches United Nations Compulsory Conciliation Proceedings on Maritime Boundaries with Australia’, Media release, 11 April 2016).

The action, explained by a government fact sheet, raised complex legal issues as it involved, inter alia, U.N.C.L.O.S. dispute resolution provisions, Australia’s unilateral 2002 withdrawal from U.N.C.L.O.S. processes for maritime boundary disputes, and the ‘gag rule’ in C.M.A.T.S. Article 4, especially paragraph 6. Nevertheless, as a spokesperson for Timor-Leste explained on Australia’s Radio National, Timor-Leste is frustrated with Australian intransigence for the past 14 years, concerned that ‘provisional’ arrangements could evolve to become permanent, and seeks to look toward the future and accelerate the eventual settlement of the maritime boundary as foreseen in the existing revenue-sharing agreements. Timor-Leste’s initiative, which is the first time ever that this process has been invoked, was reported by the press and the A.B.C. (T. Allard, ‘East Timor takes Australia to UN over sea border’, The Sydney Morning Herald, 11 April 2016).

The Australian Government sharply criticised the move, and announced that there would be no further discussions. However, the Australian Labor Party and the Greens Party welcomed Timor-Leste’s action, promising to negotiate a new and fair maritime boundary with Timor-Leste, and Special Broadcasting Service compared contrasting party policies. (H. Sinclair, ‘Contrasting party policies emerge over maritime boundary with East Timor’, 14 April 2016).

On 13 April former Prime Minister and Chief Boundary Negotiator Xanana Gusmão brought the issue to the attention of the Secretary-General Ban Ki-Moon at the United Nations in New York. Xanana Gusmão issued a press statement there, and the Government issued a press release in Dili (‘H.E. Kay Rala Xanana Gusmão meets with UN Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon as Timor-Leste initiates Compulsory Conciliation under UNCLOS’, Media release, 14 April 2016).

Several Australians with long connections to Timor-Leste, including academics, journalists and geologists, wrote articles to place the current dispute in historical context. Timorese veterans, diplomats and negotiators reached out to people in Australia and the region. Former President Jose Ramos-Horta wrote “Australia needs to negotiate not litigate with neighbours” in major Australian newspapers. (Jose Ramos Horta: Australia needs to negotiate not litigate with neighbours, The Sydney Morning Herald, 24 April 2016).

The Sydney Morning Herald carried a column titled: ‘Australia is a bad neighbour and we should be better than this’ (2 May 2016) and reported that East Timor’s Xanana Gusmão says small nations angry with Australia, and will put bid for UN seat in peril (by T. Allard, 1 May 2016).

When Timor-Leste filed for Compulsory Conciliation on 11 April, it named Judge Abdul Koroma (from Sierra Leon, who had sat on the International Court of Justice from 1994 to 2012) and Judge Rüdiger Wolfrum (from Germany, who had been on the International Tribunal for the Law of the Sea since 1996) as their chosen members of the panel. On 2 May Australia selected Dr. Rosalie Balkin (an Australian, and a retired Assistant Secretary-General of the International Maritime Organization) and Professor Donald McRae (a Canadian/New Zealander who was teaching law at the University of Ottawa) as its two representatives. These four were to elect a fifth member to chair the Conciliation Panel.

Still, Australian continued its scare tactics, suggesting that Indonesia “may be drawn into Timor talks”, yet conveniently forgetting that, in Article 4 of the 1972 Australia-Indonesia Seabed Boundary Treaty, the signatories agreed to “cease to claim or to exercise sovereign rights with respect to the exploration of the seabed and the exploitation of its natural resources beyond the boundaries so established.” Furthermore, Indonesia had ceded what became the J.P.D.A. and the area east and west of it to Australia through that treaty.

Whistleblower Witness K, who exposed Australias bugging of Timor-Leste’s Government offices during the C.M.A.T.S. negotiations, was recognised at the ‘Blueprint Prize for Free Speech’ awards in London (‘Witness K gets international recognition’, Crikey, 9 May 2016).

In May 2016 Mr. Marc Moszkowski published an updated version of his map presentation ‘Maritime boundaries of East Timor: a graphical presentation of some historical and current issues’. Mr. Moszkowski is highly qualified for the position. He is the President of Deep Gulf Inc. of Florida, USA; an engineer and master mariner with superior experience in the Timor Sea and has led projects for the first detailed bathymetric survey of parts of the Timor Sea, as well as surveys commissioned by the Secretary of State for Natural Resources of strategic parts of the southern shore including Beaco and Suai for the Tasi Mane project of the Government of East Timor. He updated his Timor Sea Maritime Boundaries with a presentation for the ICJA/ILA Colloquium, held at University of New South Wales, on 16 August 2014.

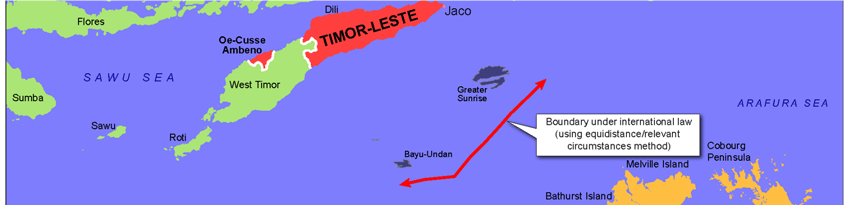

The very complex and highly documented work contains an interesting slide reproducing the boundary claimed by the East Timorese Government on 29 February 2016.

In the slide a median line between Timor-Leste and Australia is drawn. The median lines with Indonesia are not shown. Several I.C.J. case examples were provided (Libya v. Malta, Romania v. Ukraine, Bangladesh v. Myanmar, Nicaragua v. Colombia, and Peru v. Chile).

In June several feature articles, actually too many to list, tried to explain the context and analyse Timor-Leste’s and Australia’s perspectives. Most of the articles were quite unflattering. (T. McDonald, ‘Australia row hampers East Timor’s oil ambitions’, B.B.C. News, 13 June 2016; T. Iltis, ‘How Australia is screwing East Timor’, Green Left Weekly, 25 June 2016; Rob Wesley-Smith asked some important questions, re various conferences on Timor Sea matters, 30 June 2016).

Before the Australian Parliamentary election on 2 July 2016 the Foreign Minister and shadow Foreign Minister debated Australia’s policy toward Timor-Leste. Both women were re-elected to Parliament, but neither party had an absolute majority, so the composition of the new government in Canberra remained unclear. Two weeks later, it was agreed that Malcolm Turnbull would continue as Prime Minister.

On 12 July the Permanent Court of Arbitration ruled against China’s claim to most of the maritime territory in the South China Sea, upholding the Philippines’ argument that the claim violated the U.N. Convention on the Law of the Sea, and countries in the region reacted. Timor-Leste supporters pointed out the parallels with the Timor-Leste v. Australia dispute, and Australian Foreign Minister Julie Bishop displayed her government’s inconsistency.

The Sydney Morning Herald emphasised that ‘Australia is guilty of same misconduct as China over our treatment of East Timor’, by T. Clark, 14 July 2016.

International lawyers analysed ‘The Shifting Sands below the Sea, The landmark decision on the South China Sea, and it implications for Australia and Timor Leste’, by Gilbert & Tobin, 13 July 2016, while the Timor-Leste Government reaffirmed its commitment to U.N.C.L.O.S. (‘Government reaffirms commitment to UNCLOS as the ‘constitution of the sea’ ’, Media release, 15 July 2016).

The Compulsory Conciliation Panel had not agreed on the choice of their fifth member by 18 June, and Timor-Leste’s spokesperson told local papers that U.N. Secretary-General Ban Ki Moon would probably have to select him or her. Ten days later, however, the four members reached agreement on Ambassador Peter Taksøe-Jensen (a Dane and at the time Denmark’s ambassador to India and former U.N. Assistant Secretary General for Legal Affairs). The panel held its first procedural meeting in The Hague on 28 July, as announced by the Permanent Court of Arbitration and by Timor-Leste’s government. (‘The Conciliation Commission Concludes First Procedural Meeting’, Media release, 30 July 2016).

The next hearing was to be held on 29-31 August on “the background to the conciliation and certain questions concerning the competence of the Commission.” As announced by the P.C.A. and echoed by Timor-Leste and Australia, the opening statements were web-streamed live, 29 August 2016.

The Saturday Paper published Hamish McDonald’s interview with José Ramos-Horta who said that Xanana Gusmão “was never very supportive of the 2002 and 2006 treaties.” (H. McDonald, ‘Q&A with international pacemaker José Ramos-Horta’, The Saturday Paper, 30 July 2016).

As the opening of the Conciliation Process drew near, Timor-Leste’s Government announced its delegation: the Minister of Planning and Strategic Investment and Chief Negotiator for Maritime Boundaries, H.E. Kay Rala Xanana Gusmão, and the Minister of State and of the Presidency of the Council of Ministers, H.E. Agio Pereira. (‘Members of Government to attend Conciliation Commission hearing next week’, Media release, 23 August 2016).

The Government also presented a policy paper to the Council of Ministers. The 92-page paper was announced by the Government and launched by Prime Minister Rui Araùjo in Dili just hours before the Conciliation process opened in The Hague. (‘Speech by His Excellency the Prime Minister of the Democratic Republic of Timor-Leste, Dr. Rui Maria de Araúio, at the launch of the Timor-Leste policy paper on maritime boundaries’, Dili, 29 August 2016).

The Timor-Leste’s Government Maritime Boundary Office prepared a Fact Sheet on the conciliation process: ‘Timor-Leste Conciliation with Australia on Maritime Boundaries.

Australia’s position on the upcoming conciliation was confused when Foreign Minister Julie Bishop stated that Australia accepted rule of law for boundary disputes, but reversed that position in relation to this process. (M. Skulley, ‘Aus govt defends status quo in Timor Sea’, 29 August 2016) However, But Professor Ben Saul pointed out that the conciliation was a new opportunity for Australia to do the right thing. (B. Saul, ‘On Timor, Australia looks it’s denying an impoverished neighbour its birthright’, 29 August 2016). The A.B.C. News put the upcoming hearing in context. (‘East Timor-Australia maritime border dispute to be negotiated at the Hague’, 29 August 2016).

On 28 August Timor-Leste and Australia made their opening statements to the Conciliation Commission. (Permanent Court of Arbitration, Case No. 2016-10, Conciliation Proceedings between the Government of the Democratic Republic of Timor-Leste and the Government of the Commonwealth of Australia, pursuant to Art. 298 and Annex V of the U.N. Convention of the Law of the Sea, Opening Session, Monday 29 August 2016, Commissioners: H.E. Mr Peter Taksøe-Jensen (Chairman), Dr. Rosalie Balkin, Judge Abdul G Koroma, Professor Donald McRae, Judge Rüdiger Wolfrum).

Timor-Leste urged Australia to negotiate a boundary, while Australia rejected the Commission’s power to engage in this issue. (D. Flitton, ‘Australia rejects jurisdiction of East Timor’s bid to broker maritime dispute’, The Sydney Morning Herald, 29 August 2016).

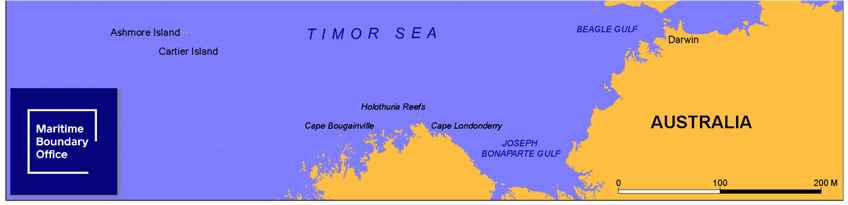

The map is a demonstration of the dispute of the contending parties according to maps prepared by Timor-Leste and Australia at the opening of the Conciliation process in August 2016

After the opening hearing, the Australian Foreign Minister summarised her government’s position, while the Australian Embassy in Dili published answers to frequently asked questions, and Timor-Lestes Maritime Boundaries Office summarised the public session.

The Commission met in closed session for a few days, issuing a press release on proceedings. (Press release, ‘Conciliation between the Democratic Republic of Timor-Leste and the Commonwealth of Australia’, The Hague, 31 August 2016, Commission Holds Public Opening Session in Conciliation Proceedings).

The conclusions of the process were reported by the Australian press. (D. Flitton, ‘Special commission quizzes Australia and East Timor in bid to broker sea dispute’, The (Melbourne) Age, 2 September 2016), which emphasised that East Timor deserves a fair hearing. (‘East Timor deserves a fair hearing on maritime boundary’, The (Melbourne) Age, 5 September 2016).

The positions of the parties on the conciliation process were amply commented upon. (Prof. D. Anton, ‘Right but wrong: Australia is using a legalism to delay resolution of the Timor sea boundary dispute’, WAtoday, 31 August 2016; H. McDonald, ‘Timor-Leste backing oil development before Hague ruling’, The Saturday Paper, 3 September 2016).

On 9 September the Permanent Court of Arbitration adopted Rules of Procedure for the arbitration case under the Timor Sea Treaty which Timor-Leste had initiated in April 2013. (P.C.A. Case Nº 2015-42, in the matter of the arbitration under the Timor Sea Treaty of 20 May 2002 between the Democratic Republic of Timor-Leste and the Commonwealth of Australia case concerning the meaning of Art. 8(b) – Rules of procedure).

On 26 September the Conciliation Commission released its 41-page unanimous ‘Decision on Australia’s Objections to Competence’, affirming that it did have jurisdiction and would have continued to hear the case over the following twelve months. The decision was applauded by Timor-Leste (‘Timor-Leste welcomes Conciliation Commission’s landmark decision to proceed’, Media release, 26 September 2016) and accepted by Australia (‘Timor Sea Conciliation’, Joint media release, The Hon. Julie Bishop, Minister for Foreign Affairs Senator the Hon. George Brandis QC, Attorney-General, 26 September 2016) It was widely covered in the international media.

On 13 October the Permanent Court of Arbitration announced, on the Conciliation Commission’s behalf, that Optimism Pervades Recent Meetings with Conciliation Commission, saying that both Australia and Timor-Leste delegations are actively participating and consider the meetings “very productive,” although confidentiality prevents either party from commenting publicly. (P. C. A., ‘Conciliation between the Democratic Republic of Timor-Leste and the Commonwealth of Australia’, Press release, Optimism pervades recent meetings with Conciliation Commission, Singapore, 12 October 2016) Yet the process would continue in 2017.

When António Manuel de Oliveira Guterres was elected U.N. Secretary-General, the former President José Ramos-Horta explained that Guterres could not use his new position to tilt the playing field towards Timor-Leste in the boundary dispute. Horta later appealed to Australia’s sense of a ‘fair go’. (T. Moore, ‘Nobel laureate calls on Australia to show ‘fair go’ over $40b Timor Sea oil’, The Sydney Morning Herald, 27 October 2016).

In November The Australia Institute released the results of a poll of Australians conducted he previous August. Of the 10,271 Australian residents polled, 56.5 per cent supported establishing a maritime boundary according to international law, while only 17 per cent opposed this change.

The November issue of the R.D.T.L. Maritime Boundary Office Newsletter summarised its recent activities.

In December 2016 Timor-Leste and Indonesia discussed opportunities for cooperation in the oil and gas sector. (‘Exchange between Timor-Leste and Indonesia in the area of oil and gas’).

On 9 January 2017 Timor-Leste, Australia and the Conciliation Commission issued a joint statement. The two countries agreed to terminate the 2006 C.M.A.T.S. Treaty in its entirety, including the “zombie clauses” which would have kept parts of the treaty alive after “termination” and resurrected it when Sunrise production began. The termination was to be effective as from 10 April, three months after Timor-Leste legally would notify Australia that it was exercising its right to terminate under the treaty. The 2002 Timor Sea Treaty would expire on its original date (April 2033), rather in 2057 as defined by C.M.A.T.S. The two governments also committed to negotiate permanent maritime boundaries, and the C.M.A.T.S. ‘gag rule’, that Timor-Leste had been defying for the previous three years, was no longer in effect. (‘Joint Statement by the Governments of Timor-Leste and Australia and the Conciliation Commission constituted pursuant to Annex V of the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea’).

By the decision both governments had finally agreed on the following points: 1) Any bilateral treaty could be changed or voided at any time by mutual agreement of both countries; 2) The ‘gag rule’ which prevented recourse to diplomacy, advocacy or international mechanisms was ill-considered and bad for Timor-Leste; 3) A permanent maritime boundary, rather than temporary revenue-sharing agreements, would more likely respect the sovereignty and national interests of both countries.

Unfortunately, the joint statement did not address another key point: that a binding ruling by an impartial third party – through arbitration or a judicial process – is the only fair way to settle a boundary dispute between two very unequal countries. Since Timor-Leste restored its independence in 2002, closed-door bilateral negotiations had produced results biased towards Australia, which has far more wealth, experience, flexibility, resilience, oil and gas, and economic and political resources. Timor-Leste would continue to urge Australia to return to the binding dispute resolution mechanisms under the International Court of Justice and U.N.C.L.O.S. from which it withdrew two months before Timor-Leste became a sovereign nation.

The 9 January joint announcement was widely reported by international media. (D. Flitton, ‘Spying fallout: East Timor to tear up oil and gas treaty with Australia’, The (Melbourne) Age, 9 January 2016).

On 10 January Timor-Leste’s Parliament resolved to cancel the C.M.A.T.S. Treaty, and President Taur Matan Ruak promulgated Resolution 01/2017 six days later. (Jornal da República, Série I, N.° 2A, Página, 2 Segunda-Feira, 16 de Janeiro de 2017, Resolução do Parlamento Nacional N.º 01/2017 de 16 de Janeiro) Prime Minister Rui Araùjo told local journalists that oil and gas exploration in the Timor Sea would be temporarily suspended until the boundary was settled.

According to the A.B.C., Woodside was hopeful that a boundary settlement would allow its Sunrise project to move forward, while another A.B.C. report cited economic opportunities for Timor-Leste. (A.B.C., E. Stewart, ‘Woodside Petroleum [was] waiting on Australia-East Timor maritime deal to develop Greater Sunrise’, 10 January 2017; A.B.C., K. Gregory, ‘East Timor to capitalise on economic opportunities’, 10 January 2017).

However, a few days later, a contributor to the A.B.C. explained that Sunrise would have faced a long road, with political and economic hurdles, while The Australian Financial Review discussed the problems for Darwin LNG caused by “fresh uncertainty.” (A. Macdonald-Smith, ‘Timor Sea turmoil complicates life for Darwin LNG’, The Australian Financial Review, 12 January 2017).

It was back to the drawing board for a maritime agreement between Australia and Timor-Leste.

Journalists with long Timor-Leste experience gave deeper explanations, as did – among others – an Australian academic. (M. Leach, ‘A line in the water, Inside story’, 12 January 2017; see also: P. Kelly, ‘Australian government agrees to negotiate East Timor maritime border’, World Socialist Web Site, 11 January 2017).

On 18 January Al Jazeera’s The Stream hosted a half-hour TV programme on the issue, with José Ramos-Horta, Tom Clarke, Juvinal Dias and Mark Mozkowski. The Australian government declined to participate. (On The Stream: The Stream takes a look at Australia and East Timor’s long-standing maritime boundary dispute, The Stream – Maritime row in the Timor Sea’, Al Jazeera English, published on 19 January 2017).

There followed another statement by the two countries, in which the two countries “reaffirmed their commitment to work in good faith towards an agreement on maritime boundaries by the end of the conciliation process in September 2017.” (‘Joint Statement by the Governments of Timor-Leste and Australia and the Conciliation Commission constituted pursuant to Annex V of the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea 20 January 2017’). The statement was reported by the international media. (D. Flitton, ‘East Timor dumps spying case against Australia for ‘good faith’ oil, gas boundary talks’, The Sydney Morning Herald, 24 January 2017).

Timor-Leste had dumped its spying case against Australia in the international court, raising hopes of an eventual end to the bitter stand-off over $ 40 billion in oil and gas fields. Two months later the arbitration panel formally ended the process. Specialized international publications explained the issue to their constituencies.

In February Inter Press Service published Maritime Boundary Dispute Masks Need for Economic Diversity in Timor-Leste by Stephen de Tarczynski.

Continued Wednesday – The spying on Timor-Leste case … et cetera (part 6)

Previous instalment – The spying on Timor-Leste case … et cetera (part 4)

Dr. Venturino Giorgio Venturini devoted some seventy years to study, practice, teach, write and administer law at different places in four continents.

Dr. Venturino Giorgio Venturini devoted some seventy years to study, practice, teach, write and administer law at different places in four continents.

Like what we do at The AIMN?

You’ll like it even more knowing that your donation will help us to keep up the good fight.

Chuck in a few bucks and see just how far it goes!

Your contribution to help with the running costs of this site will be gratefully accepted.

You can donate through PayPal or credit card via the button below, or donate via bank transfer: BSB: 062500; A/c no: 10495969

That is why it is easier for people who have not studied economics, to accept it. Their minds have not been polluted with gold standard thinking. Common sense takes over.

That is why it is easier for people who have not studied economics, to accept it. Their minds have not been polluted with gold standard thinking. Common sense takes over. Engaging in a carefully considered language with simplistic clarity, a language that has factored in all the elements of disbelief and fear is a huge challenge.

Engaging in a carefully considered language with simplistic clarity, a language that has factored in all the elements of disbelief and fear is a huge challenge. After all, who can seriously say that the present theory of classical economics has proved itself worthy?

After all, who can seriously say that the present theory of classical economics has proved itself worthy?