Our mate: Saddam Hussein al-Tikriti (part 7)

By Dr George Venturini

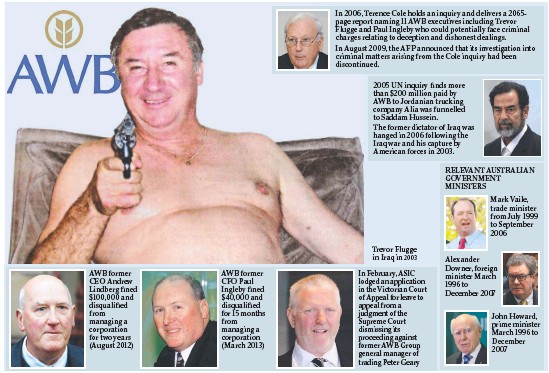

In 2005 the Cole Inquiry heard that between 1999 and 2004 the A.W.B. had systematically paid almost AU$300 million in illicit fees and ultimate ‘kickbacks’ to Saddam Hussein’s regime.

A.S.I.C. had placed the civil cases, which had been initiated in late 2007, against Mr. Flugge and five other former A.W.B. executives on hold in November 2008 to await for possible criminal charges but in a shock decision in mid-2010, it was revealed that the criminal aspects of the long-running A.W.B. investigation had been abandoned.

A.S.I.C. re-ignited the civil penalty cases against the six men over the payment of hundreds of millions of dollars in “transport”, “discharge” and “sales service fees” to Jordanian-based trucking company Alia, which payments turned out to be ‘kickbacks’ to Saddam Hussein’s régime.

In 2013 A.S.I.C. had won two rather unimportant civil cases against former managing director Andrew Lindberg – who was sentenced to pay a penalty of $100,000, and against former chief financial officer Paul Ingleby – who was sentenced to pay a penalty of $40,000.

Cases against former directors Michael Long and Charles Stott had been dismissed. A search of the public records revealed the ‘corporate regulator’ had spent an estimated $15 million on the A.W.B. prosecutions at that time.

A.S.I.C. had not gained the best result with Justice Robson over the A.W.B. cases, after he dismissed one of the ‘corporate regulator’ two cases against Mr. Lindberg, while ruling that the agreed $40,000 fine against Mr. Ingleby was too tough – a decision which was over-ruled on appeal.

A.S.I.C. was bound to prove that Mr. Flugge, an experienced director, knew or ought to have known that A.W.B. was breaching the United Nations Security Council Resolutions – and it failed. (P. Durkin, ‘Former AWB chairman Trevor Flugge finally faces court’, The Australian Financial Review, 11 October 2015).

The Iraqi wheat-‘kickbacks’ scandal was set to reignite headlines again in 2016.

The mid-2000s scandal involving Prime Minister Howard, Foreign Minister Downer, and Trade Minister Vaile did not seem ‘to go away’.

It was thought at mid-2009 that the reason why Australia had slipped down the international anti-corruption rankings was because of the A.W.B. Oil-for-Food scandal.

Transparency International keeps on lamenting that many governments simply are not putting enough effort into curbing bribes. Some years ago the organisation evaluated the efforts member countries were making to uphold the O.E.C.D.’s Anti-Bribery Convention. Australia did come out in the bottom category, criticised for carrying out little or no practical enforcement against bribery offenses by national businesses operating overseas. That was a category shared by 21 O.E.C.D. countries, as diverse as Brazil, Canada and Turkey. Only four countries were in the top tier, cited for active enforcement, with eleven in the middle with moderate enforcement. In such a climate there was a risk that, unless enforcement both improved and became more uniform across countries, the Anti-Bribery Convention could become irrelevant. A Convention like this cannot afford to fail, otherwise it becomes one of those international conventions which are more valuable on paper than in practice. That would not have disturbed Australian governments after the Royal Ambush. Today, practically no significant international treaty or convention ratified by Australia is abided by.

Especially over the decades prior to the Convention, multinational corporations have helped bribery and corruption become a much worse problem especially in developing countries. As the multinational corporations, especially American and European, went abroad to countries which were vulnerable, the scale of the bribes increased – greedy officials would demand more from foreign investors.

This was particularly a problem in the resources sector, and distorted several national economies.

The Transparency International reports look at how many foreign investment corruption cases have gone to court, year by year – and how many have resulted in convictions. While not specifically including bribes, Australia’s biggest overseas corruption case around 2009-2010 was the Iraq Oil-for-Food scandal and the Australian Wheat Board. Six cases were at the time in the civil courts, but none had yet resulted in convictions – and even the moderate recommendations from the Cole Inquiry into the affair had not been followed up. The lack of results had placed Australia in the bottom group. Countries like the United States and Germany, which have both prosecuted several cases, served as a clear contrast in the top category.

Clearly the A.W.B. scandal would not go away, no matter what the Howard Government would do. It was the prevailing opinion that, apart from that scandal, the government itself was incompetent, dishonest and corrupt. It has been proven so in relation to its accountability and other processes following the discovery of restricted and secret intelligence reports and communications between various Australian embassies, trade officials, the United Nations, Australian public servants and the Australian Prime Minister, the then Minister for Trade, who was also Deputy Prime Minister, and the Foreign Minister and their Departments in relation to the A.W.B. scandal.

New evidence and supporting material had come to light during an independent investigation into claims that Members of Parliament were holding ‘dirt files’. The ‘dirt files’ claims had been proven in the process of the investigation, and a substantial amount of material related to the A.W.B. scandal as well as documents related to other issues had been discovered. Much of the A.W.B. material was held by various Australian agencies and had not been brought to the attention of the Cole Inquiry into the bribes ultimately flowing to the Saddam Hussein’s régime.

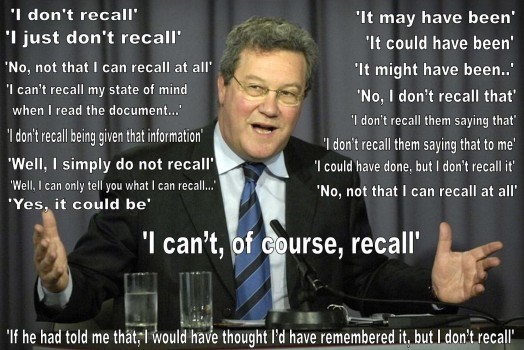

The available material showed that, in fact, senior Government ministers were told on a number of occasions that the A.W.B. was providing bribes to Saddam Hussein’s régime, contrary to the provisions of the United Nations Oil-for-Food programme. Copies of confidential and secret diplomatic cables, memoranda, e-mails and other material were found showing that both the then Minister for Trade as well as the Foreign Minister, had received numerous detailed intelligence and other briefings very early on into the scandal. They did nothing. The Foreign Minister noted in one secret memorandum to the Australian Embassy in Jordan that: “No-one will ever find out anyway.”

Image from Independent Australia

The then Minister for Trade was also advised on a number of occasions as to what was going on. Prime Minister Howard was also briefed on the matter by the various agencies including the Office of National Assessment, as well as the Australian Secret Intelligence Service, Australia’s international spy agency.

The same Howard Government which had kept silent over what it knew of the Oil-for-Food scandal set out ‘to detect, investigate and prevent corrupt conduct’ through the newly formed Australian Commission for Law Enforcement Integrity, A.C.L.E.I., with an Office of the Integrity Commissioner.

The Commission was established by an Act of Parliament in 2006, and placed under the responsibility of the Home Affairs and Justice Minister. A.C.L.E.I.’s role is to detect, investigate and prevent corruption in the Australian Border Force, Australian Crime Commission, Australian Federal Police (including A.C.T. Policing), Australian Transaction Reporting and Analysis Centre (AUSTRAC), CrimTrac Agency, prescribed aspects of the Department of Agriculture, Department of Immigration and Border Protection, and the former National Crime Authority. Other agencies with a law enforcement function may also be added by regulation. A.C.L.E.I’s primary role is to investigate law enforcement-related corruption issues, giving priority to serious and systemic corruption. The Integrity Commissioner must consider the nature and scope of corruption revealed by investigations, and report annually on any patterns and trends in corruption in Australian Government law enforcement and other Government agencies which have law enforcement functions. Accordingly, A.C.L.E.I. collects intelligence about corruption in support of the Integrity Commissioner’s functions. A.C.L.E.I. also aims to understand corruption and prevent it. When, as a consequence of performing her/his functions, the Integrity Commissioner identifies laws of the Commonwealth or administrative practices of government agencies which might contribute to corrupt practices or prevent their early detection, s/he may make recommendations for these laws or practices to be changed. Any person, including members of the public and law enforcement officers, can give information to the Integrity Commissioner. Information can be given in confidence or provided anonymously.

Well Juvenal could ask: Quis custodiet ipsos custodies? – “Who will guard the guards themselves?”

After all, who would know about a little bit of corruption work, promoted by ‘benevolent’ organisations such as the one rendered public by the Victoria Ombudsman in March 2011. And the innocent name? – The Brotherhood. The ‘brothers’ meet for lunch, to hear a guest speaker and then to engage in a bit of ‘networking’.

What the Ombudsman discovered about The Brotherhood confirmed the widely held conviction that its activities undermine the community’s confidence in public institutions.

Invitees from a list of up to 350 influential people had been attending the lunches every six weeks since the first one was held in 2003. The guests are all men, and the Chatham House Rule applies, i.e. “What is said in the room stays in the room.”

The host has been from the beginning the founder, a former policeman between 1988 and 1999, who had come to the attention of the Police Internal Investigations Department for, among other transgressions, assaulting a member of the public, and fined $200. He came to head two private companies. The founder started the lunches with the statement: “We are all members of The Brotherhood and we must assist each other.”

A whistleblower told the Ombudsman that “[the founder’s] motivation for the formation and maintenance of this group is to, amongst other things, provide an environment to facilitate unlawful information trading including confidential police information and other confidential information from government departments. This is in addition to gaining commercial benefits and inside information regarding contracts for tender.”

On the invitation list were two ‘Liberal’ State M.P.s, many current and former police officers including one with alleged links to an organised crime figure. A former Australian Wheat Board executive involved in the Oil-for-Food scandal was on it, too. So was the manager of a licensed table- top-dancing venue frequented by Victoria Police officers.

Some of the public servants attending maintained databases of sensitive information. It seems that a regular attendee, a senior Victorian Police officer, disclosed the identity of a prosecution witness in a high-profile murder trial, contrary to a Supreme Court suppression order. One member used his position at the Traffic Camera Office to annul over $2,000 worth of speeding fines accumulated by the founder and persons of his companies. The ‘operator’ denied any wrongdoing, but the case was recommended to police for investigation.

The example of The Brotherhood is not unique. The Ombudsman’s report cited the New South Wales Independent Commission Against Corruption’s investigations into the ‘Information Exchange Club’ in 1992. This could be added to the mountain of damning reports and inquiries including Royal Commissions into various state Police forces over the decades. Nothing ever seems to happen. ‘Revolving door’ appointments involving positions on boards for retiring, previously highly placed politicians have become routine.

Of course, the preceding are just some examples of unlawful behaviour. The most notorious scandals of the last decade include: Trio Capital; the Commonwealth Bank financial planning scandal; CommInsure; the ANZ insider trading scandal; the bank bill swap rates fixing scandal, which now involves three of the big four banks; Storm Financial; Opes Prime; the Financial planning scandals at Westpac, NAB and Macquarie Private Wealth; the LM Investments; Bribery allegations against ASX boss Elmer Kunke Kupper; the ‘managed investment schemes’ (MIS) fiasco (Timbercorp, Great Southern); the Insider trading between an ABS bureaucrat and a NAB banker; and the Reserve Bank Securency scandal.

Perceptions of corruption in the Australian Government and public sector increased in 2018 for the seventh year running, surging eight points since 2015, and remaining in 2018 the same as in 2017 – in an annual index by Transparency International.

Since its inception in 1995, the Corruption Perceptions Index – Transparency International’s flagship research product, has become the leading global indicator of public sector corruption. The index offers an annual snapshot of the relative degree of corruption by ranking countries and territories from all over the globe. In 2012 Transparency International revised the methodology used to construct the index to allow for comparison of scores from one year to the next. The 2018 C.P.I. draws on 13 surveys and expert assessments to measure public sector corruption in 180 countries and territories, giving each a score from zero (highly corrupt) to 100 (very clean).

The result puts Australia in thirteenth place globally for perceived openness, the country’s equal lowest ranking in the 23-year history of the report.

Australia’s 2018 score was 77, down from 85 in 2012. Denmark came in first with 88, with New Zealand second (87), followed by Finland (85), even with Singapore (85), Sweden (85), and Switzerland (85), Norway (84), Netherlands (82), Canada (81), even with Luxemburg (81), Germany (80), even with United Kingdom (80). Somalia is the last (10), preceded by South Sudan and Syria (13) and North Korea and Yemen (14).

The former chair of Transparency International Australia, Anthony Wheatley, Q.C., has had occasion to say that Australia’s score was “the result of inaction from successive governments who have failed to address weaknesses in Australia’s laws and legal processes.”

Foreign bribery scandals such as those involving the Australian Wheat Board and Securency had damaged Australia’s reputation and legislation introduced into parliament in December 2015 was “long overdue”, he said.

Transparency International has also been calling for a federal anti-corruption agency; a nationally consistent and tighter political donations disclosure regime; and safeguards against dirty money from overseas bleeding into the Australian finance or real estate industries.

Muscular anti-foreign bribery laws and political donations reform were required to help arrest the slide. Mr. Wheatley said that addressing weaknesses in government would also raise the bar for the private sector.

The links between public institutions and big business interests – both mainstream and underworld – are becoming well known to the public, but one would be an optimist for thinking that anger at the seemingly endless stream of scandals is growing. It is pressure from the community which leads to the inquiries. It is in response to this same outrage that instrumentalities like the state-based Independent Commissions Against Corruption were established.

The demand on big business to abide by their State ‘rule of law’ is certainly justified; and the fight to bring business ‘operators’ to heel must continue. But so long as governments rule on behalf of corporations and the real power in society belongs to an oligarchy the battle will never be successful.

On 15 December 2016 the ‘corporate regulator’ lost its long-running case against former A.W.B. chairman Trevor Flugge and former executive Peter Geary on all but one allegation, more than a decade after the U.N. Oil-for-Food scandal.

On that day the Supreme Court of Victoria heard that the Australian Securities and Investments Commission had succeeded in proving just one breach by Mr. Flugge.

Mr. Flugge was facing four allegations of breaching his director’s duties, while Mr. Geary faced thirteen allegations of breaching his executive duties.

A.S.I.C had alleged the two former executives breached their duties as directors in overseeing that some AU$229 million would flow as ‘kickbacks’ to Saddam Hussein’s régime between 1999 and 2003 in order to secure lucrative Iraqi wheat contracts.

A.S.I.C. claimed that Mr. Flugge had breached his duty of care under section 180(1) of the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth) by failing 1) to ensure A.W.B. did not breach U.N. sanctions; 2) to ascertain whether A.W.B. had sought and gained U.N. approval for the payment of inland transportation fees; 3) to make inquiries of A.W.B.’s senior management about the propriety of the payments; and 4) to ensure the A.W.B. Board and/or Board Committees were properly informed of, and responded appropriately to, the matters in issue.

A.S.I.C. also alleged that Mr. Flugge knew the fee payments were being made by A.W.B. to Iraq in breach of U.N. sanctions, that they were a sham, and, hence, they were improper. Accordingly, argued A.S.I.C., Mr. Flugge had breached his section 181 of the Corporation Act on the duty to act for a proper purpose and in good faith in the best interests of A.W.B.

A.S.I.C. later alleged – and the Court accepted – that in March 2000, Mr. Flugge attended a meeting with the Australian Trade Commission in Washington, D.C. during which attendees were informed that the United Nations had concerns about irregularities in A.W.B.’s contracts and dealings with Iraq under the Oil-for-Food programme.

In turn, Mr. Flugge submitted – and the Court accepted – that in mid-2000, Mr. Flugge and other members of the A.W.B. Board were informed by the managing director that the payments had been approved by the United Nations. The evidence also established that Mr. Flugge had told a number of other people that he had believed the managing director’s statements.

The Court, however, found that A.S.I.C.’s allegations were not proved.

Judge Ross Robson dismissed the claim, declaring that he was not satisfied that Mr. Flugge knew. But he did find that, had Mr. Flugge inquired into the issues raised by the United Nations, he would have discovered that it had not knowingly approved of the payments.

Judge Robson found Mr. Flugge’s reputation for honesty had not been tarnished by the civil case brought by the ‘corporate regulator’, which failed to prove he had known the payments contravened United Nations sanctions.

In handing down his judgement, Judge Robson said that, if Mr. Flugge had made inquiries, he would have uncovered the fraud and stopped the corrupt payments.

“It is relevant that Mr. Flugge has been left to face the accusations of A.S.I.C. almost alone, when many other A.W.B. executives have avoided being proceeded against,” he said.

“The Australian community, however, has every right to be profoundly disappointed in A.W.B.’s conduct and the ignominy that it brought on Australia and the damage suffered by its shareholders.

Nevertheless, the Court should be circumspect in not adding onto Mr. Flugge the sins of others within A.W.B. who have escaped being penalised.”

The Court held that, following the Washington meeting, Mr. Flugge was duty bound to make inquiries as 1) to whether the inland transportation fee payments were irregular, 2) why it was suggested they were irregular, and 3) why the United Nations would raise the issue of irregular fee payments if the U.N. had approved the payment of those fees. The failure to make these inquiries amounted to a breach of Mr. Flugge’s duty of care under section 180(1) of the Corporation Act.

The Court further held that Mr. Flugge’s reliance on the assurances of the managing director did not relieve him of his duty to make proper inquiries, noting that “a director is not excused from making his own inquiries by relying on the judgment of others.”

Additionally, the Court held that the duty to make inquiries is an ongoing obligation and so Mr. Flugge’s breach continued until he lost his position on the board.

Judge Robson said that the A.S.I.C. had failed to make out its case against Mr. Flugge, except for one breach of director’s duties by failing to investigate after being told that a controversial “inland transport” fee paid by A.W.B. to the Iraqi Government was in contravention of United Nations sanctions.

“The Court finds that A.S.I.C. has not established that Mr. Flugge knew that A.W.B. was making payments to Iraq, contrary to United Nations sanctions,” Judge Robson ruled.

“The Court finds that A.S.I.C. has not established that it was well known within A.W.B. that payments were not authorised by the United Nations. … The Court finds that in mid-2000, the managing director of A.W.B., Mr. [Andrew] Lindberg expressly informed the board, including Mr. Flugge of the payments and that they were authorised by the United Nations.”

“The Court finds however that A.S.I.C. has established that Mr. Flugge breached his duties as a director … in not inquiring into the issues raised by the U.N. and that if he had done so, he would have discovered that the U.N. … had not knowingly approved of the payments in the circumstances where neither Iraq nor the A.W.B. had any responsibility to deliver wheat within Iraq,” the Judge ruled.

Justice Robson found that Mr. Flugge had acted honestly, dismissing A.S.I.C.’s assertion that he had “sat on the board ticking off codes of conduct when … he knew of a ‘very big and dark secret’ … and that ‘worse than doing nothing about it, he positively encouraged management to get on and do this dirty work’. ”

“In the scale of breaches it was certainly not egregious, but it was not the sort of breach for which a director, knowing what Mr. Flugge knew, should be excused,” Justice Robson said.

“Even if Mr. Flugge had stopped the payments … there is every likelihood that A.S.I.C. would have taken proceedings against A.W.B. executives [and] Australia’s reputation internationally would have been tarnished, shareholder class actions may have been instituted and A.W.B. may have collapsed.”

Judge Robson said that Mr. Flugge had been of great service to Australian commerce, wheat farmers and the Australian community generally and had recognised that work in fixing penalties.

The ruling came close to a decade after the Cole Inquiry found that the A.W.B. had made the secret payments in full knowledge that they were in breach of U.N. sanctions.

Continued Saturday – Our mate: Saddam Hussein al-Tikriti (part 8)

Previous instalment – Our mate: Saddam Hussein al-Tikriti (part 6)

Dr. Venturino Giorgio Venturini devoted some seventy years to study, practice, teach, write and administer law at different places in four continents. He may be reached at George.venturini@bigpond.com.au.

Dr. Venturino Giorgio Venturini devoted some seventy years to study, practice, teach, write and administer law at different places in four continents. He may be reached at George.venturini@bigpond.com.au.

Like what we do at The AIMN?

You’ll like it even more knowing that your donation will help us to keep up the good fight.

Chuck in a few bucks and see just how far it goes!