Dean Jones: Life of a Cricketing Entertainer

He was very much one of those cricketers who made the pulse race, a figure for the advocates of a faster variant of the game. Nothing of the solid blocker in the man, though he could, if needed, linger at the crease. Australia’s Dean Jones sported equipment perfect for the shorter format of the game: lightning quick between the wickets, leaving his tubbier counterparts ragged and puffed; an obsessive about keeping the runs flowing; a spirited entertainer. A stunning fielder of accuracy. An explorer in the field. Then, the slashing shots: the on drive to a delivery he would enthusiastically dispatch to the boundary on skipping to it; the lifted off drive, which would propel the ball into the stands.

In India, a country which deifies its cricketers, and burns the occasional one in effigy, the reactions of warmth and shock have been genuine. It was in a Mumbai hotel where he collapsed. It was in that same hotel that fellow cricketer and former Australian fast bowler Brett Lee attempted to revive him. India, and the subcontinent more broadly, became a place Jones promoted, coached in, commented upon. These were not outposts of hostility but places of veneration.

It was also India which witnessed one of the more remarkable, and courageous innings, of Test cricket. It was 1986. Jones had made his Test debut two years prior. He had been left out of the tour of England in 1985. Captain Allan Border heralded the Victorian’s return to the side, slotting Jones in at the No.3 position. He played an innings of near-death in the dehydrating heat of Chennai’s MA Chidambaram Stadium, making 210 and ensuring the second Test cricket tie in history. “My body still shakes when it’s over 37 degrees,” he revealed in 2016.

Jones was a Rabelaisian mess for much of an effort lasting eight hours and 23 minutes: fluids, much of it involuntary, excreted liberally in conditions of high humidity; vomiting bouts, dramatically regular. All the time, pungent sewerage smells wafting from a neighbouring canal. Psychologically, he was also given a bruising by his bullying captain. When asked if he could retire hurt on 202, Border suggested that they “get a Queenslander (the next man Greg Ritchie) out here.” His deplorable physical state has, over time, rendered that innings singular, a case as much for medical analysis as cricketing prowess.

Courage can be a disputed mantle. The innings did not impress the grounded and blunt Greg Matthews, who took ten wickets in the same match in fittingly jaunty fashion. Three decades after the match, he was gruff in memory. “The guy (Jones) was 23, in his prime, fit as a Mallee bull. If you are not fit enough to walk out there and play, don’t come whingeing to me. He lost a few kilos – just blows me away.”

The stadium was certainly no hell on earth for the batsmen, if statistics are your sort of thing. Jones “batted on a road. 1488 runs were scored for the loss of 32 wickets.” The match had also seen three other centurions: David Boon, with 122; Border, with 106 and India’s Kapil Dev, whose 119 was a feast of merriment and slaughter.

The spinner seemed more impressed by the Indian umpire V. Vikramraju, whom he regarded as the truly brave one in giving India’s last batsman, Maninder Singh, out leg before wicket. As for his own team mates, Ray Bright stood out in the chronicles of courage. “Ray was 33, unfit, Ray was sick and Ray got up.”

Such views were deftly fielded by Jones, who remarked that Matthews lacked “medical accreditation.” In his mind, he had come close to death and, as he noted in his autobiography, it was not something to be recommended. “Sometimes I feel like a man watching his own funeral from a distance, sometimes I have to refer to descriptions written at the time to fill in huge gaps in my own consciousness.”

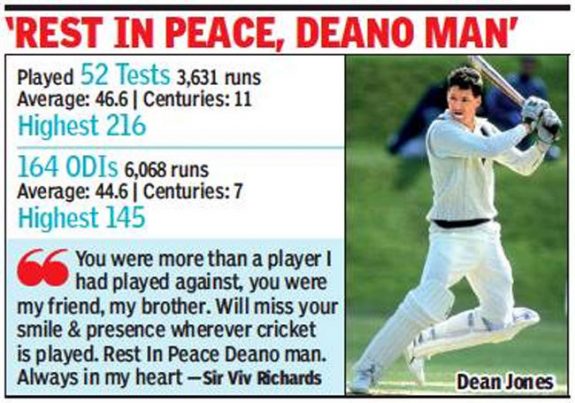

Such gaps were not in issue at the Adelaide Oval in 1989. His 216 off 347 deliveries was a spanking display against the menacing West Indian attack of Malcolm Marshall, Curtly Ambrose, Courtney Walsh and Patrick Patterson.

Jones would proceed to add to the complement of Australian cricket consciousness, withered by the retirement of that titanic trio of Greg Chappell, Dennis Lillee and Rodney Marsh; devastated into submission by the West Indian pace batteries that seemed to spring eternal; and outfoxed by English sides captained by David Gower (1985) and Mike Gatting (1986-7).

Border’s captaincy, assumed with grave reluctance, was aided by Jones, who, along with other future demigods of the game, made their names in the 1987 World Cup victory and 1989 Ashes Tour. “To 52 Tests and 164 one-day internationals,” remarked Australian cricket’s wordsmith Gideon Haigh, “he brought style, vitality and chutzpah, in a period of Australian cricket, just pre-Shane Warne, that sometimes wanted for it.”

In his sporting achievements, Jones is best associated with the one-day game: the ticking scoreboard, the thwacking of deliveries, sprinting, sun glasses, protective sunscreen, and an almost manic boisterousness. He is remembered for his faux pas at the Sydney Cricket Ground in 1993 during a World Series Cup match in which he riled the great West Indian fast bowler Ambrose. The request to the bowler was simple but impolitic: remove the white wristbands which were making the white cricket ball harder to see. The giant Ambrose, furious, picked up the pace. Australia lost that match and, eventually, the series.

Ambrose, ever sporting, remembered the man they called Deano. “He was a wonderful player. When he was walking to the crease you could see that confidence in his stride.” No signs of fear or nerves. “He was a bit of a thorn in our flesh.” A thorn of spirited entertainment, with more than a touch of talent.

Like what we do at The AIMN?

You’ll like it even more knowing that your donation will help us to keep up the good fight.

Chuck in a few bucks and see just how far it goes!

6 comments

Login here Register here-

Michael Taylor -

Jack Cade -

Michael Taylor -

Jack Cade -

Michael Taylor -

wam

Return to home pageI remember after his amazing, heroic 210 in the tied test a commentator saying that Jones let his country down.

“Why?” asked a fellow commentator.

“If he had have scored 211 – just one more run – it would have given Australia victory.”

He was, of course, joking, but it’s my favourite Jones Boy story.

I remember Jones having a discussion on the radio – during a drinks or tea break -with an Indian commentator. Deano was complaining about the pronunciation of Sunil Gavaskar’s name.

Deano – Should be pronounced as it is written. Indian pronunciations don’t make sense to me.’

Indian Commentator – I understand your problem, Mister Joe Ness’

Touché

Jack, did you know that Sunil “Sunny” Gavaskar is an uncle of Sachin Tendulkar?

Michael Taylor

No, I did not!

Two great players.

Jack, I once saw Sunny smash Thommo for three of the most beautiful cover drives in one over. It was jaw-dropping wizardry.

The nickname of ‘The Little Master’ was well-earned.

A lovely tribute, Dr Kampmark, and a great finish with Ambrose.

Jones was so mentally tough as to be fearless as demonstrated by “Jones admitted later that he scored his last hundred off just 66 balls because he couldn’t run at all.’

He had such a great cheeky charlie grin and was wonderful to watch his follow through.

I remember him being treated shabbily in missing out on the nsw/qld ashes tour in 85.

A sad loss to cricket.