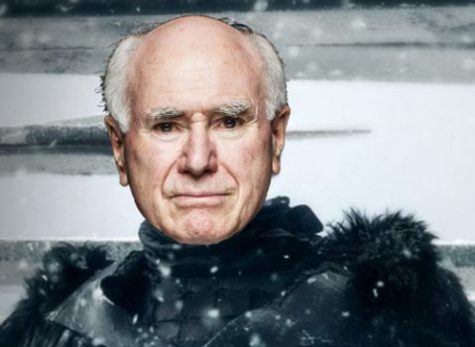

Bush, Blair and Howard – Three reckless adventurers in Iraq (Part 37)

The Iraq Inquiry Report (2009-2016) documents how Tony Blair committed Great Britain to war early in 2002, lying to the United Nations, to Parliament, and to the British people, in order to follow George Bush, who had planned an aggression on Iraq well before September 2001.

Australian Prime Minister John Howard conspired with both reckless adventurers, purported ‘to advise’ both buccaneers, sent troops to Iraq before the war started, then lied to Parliament and to the Australian people. He continues to do so.

Should he and his cabal be charged with war crimes? This, and more, is investigated by Dr George Venturini in this outstanding series.

Australia’s involvement in Iraq (continued)

In 1950 the Nuremberg Tribunal defined crimes against peace in Principle VI, specifically Principle VI(a), submitted to the United Nations General Assembly, as:

(i) Planning, preparation, initiation or waging of a war of aggression or a war in violation of international treaties, agreements or assurances;

(ii) Participation in a common plan or conspiracy for the accomplishment of any of the acts mentioned under (i).

The relevant provisions of the Charter of the United Nations mentioned in the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court article 5.2 were framed to include the Nuremberg Principles. The specific principle is Principle VI.a: Crimes against peace, which was based on the provisions of the London Charter of the International Military Tribunal, which was issued in 1945 and formed the basis for the post second world war ‘war crime trials’. The U. N. Charter’s provisions based on the Nuremberg Principle VI.a are:

CHAPTER I: PURPOSES AND PRINCIPLES

Article 1

The Purposes of the United Nations are:

- To maintain international peace and security, and to that end: to take effective collective measures for the prevention and removal of threats to the peace, and for the suppression of acts of aggression or other breaches of the peace, and to bring about by peaceful means, and in conformity with the principles of justice and international law, adjustment or settlement of international disputes or situations which might lead to a breach of the peace;

- To develop friendly relations among nations based on respect for the principle of equal rights and self-determination of peoples, and to take other appropriate measures to strengthen universal peace;

Article 2

The Organization and its Members, in pursuit of the Purposes stated in Article 1, shall act in accordance with the following Principles.

- All Members shall refrain in their international relations from the threat or use force against the territorial integrity or political independence of any state, or in any other manner inconsistent with the Purposes of the United Nations.

CHAPTER VI: PACIFIC SETTLEMENT OF DISPUTES

Article 33

- The parties to any dispute, the continuance of which is likely to endanger the maintenance of international peace and security, shall, first of all, seek a solution by negotiation, enquiry, mediation, conciliation, arbitration, judicial settlement, resort to regional agencies or arrangements, or other peaceful means of their own choice.

- The Security Council shall, when it deems necessary, call upon the parties to settle their dispute by such means.

CHAPTER VII: ACTION WITH RESPECT TO THREATS TO THE PEACE, BREACHES OF THE PEACE, AND ACTS OF AGGRESSION

Article 39

The Security Council shall determine the existence of any threat to the peace, breach of the peace, or act of aggression and shall make recommendations, or decide what measures shall be taken in accordance with Articles 41 and 42, to maintain or restore international peace and security.

The discussions on definition of aggression began at the United Nations in 1950, following the outbreak of the Korean war. As the ‘western’ governments, headed by Washington, were in favour of defining the governments of North Korea and the People’s Republic of China as aggressor states, the Soviet government proposed to formulate a new U.N. resolution defining aggression and based on the 1933 Convention for the Definition of Aggression were signed in London on 3 July 1933.

As a result, on 17 November 1950, the General Assembly passed Resolution 378, which referred the issue to be defined by the International Law Commission. The Commission deliberated over this issue in its 1951 session and due to large disagreements among its members, decided “that the only practical course was to aim at a general and abstract definition (of aggression).” However, a tentative definition of aggression was adopted by the Commission on 4 June 1951. It stated: “Aggression is the use of force by a State or Government against another State or Government, in any manner, whatever the weapons used and whether openly or otherwise, for any reason or for any purpose other than individual or collective self-defence or in pursuance of a decision or recommendation by a competent organ of the United Nations.”

On 14 December 1974 the United Nations General Assembly adopted Resolution 3314, which defined the crime of aggression. This definition is not binding as such under international law, though it may reflect customary international law.

The definition makes a distinction between aggression – which “gives rise to international responsibility” – and war of aggression – which is “a crime against international peace.” Acts of aggression are defined as armed invasions or attacks, bombardments, blockades, armed violations of territory, permitting other states to use one’s own territory to perpetrate acts of aggression and the employment of armed irregulars or mercenaries to carry out acts of aggression. A war of aggression is a series of acts committed with a sustained intent. The definition’s distinction between an act of aggression and a war of aggression makes it clear that not every act of aggression would constitute a crime against peace; only war of aggression does. States would nonetheless be held responsible for acts of aggression.

The definition is not binding on the Security Council. The United Nations Charter empowers the General Assembly to make recommendations to the United Nations Security Council but the Assembly may not dictate to the Council. The resolution accompanying the definition states that it is intended to provide guidance to the Security Council to aid it “in determining, in accordance with the Charter, the existence of an act of aggression.” The Security Council may apply or disregard this guidance as it sees fit. Legal commentators argue that the definition of aggression has had “no visible impact” on the deliberations of the Security Council.

All this premised, what follows is the adopted definition of aggression:

Article 1

Aggression is the use of armed force by a State against the sovereignty, territorial integrity or political independence of another State, or in any other manner inconsistent with the Charter of the United Nations, as set out in this Definition. [Note omitted]

Article 2

The First use of armed force by a State in contravention of the Charter shall constitute prima facie evidence of an act of aggression although the Security Council may, in conformity with the Charter, conclude that a determination that an act of aggression has been committed would not be justified in the light of other relevant circumstances, including the fact that the acts concerned or their consequences are not of sufficient gravity.

Article 3

Any of the following acts, regardless of a declaration of war, shall, subject to and in accordance with the provisions of article 2, qualify as an act of aggression:

(a) The invasion or attack by the armed forces of a State of the territory of another State, or any military occupation, however temporary, resulting from such invasion or attack, or any annexation by the use of force of the territory of another State or part thereof,

(b) Bombardment by the armed forces of a State against the territory of another State or the use of any weapons by a State against the territory of another State;

(c) The blockade of the ports or coasts of a State by the armed forces of another State;

(d) An attack by the armed forces of a State on the land, sea or air forces, or marine and air fleets of another State;

(e) The use of armed forces of one State which are within the territory of another State with the agreement of the receiving State, in contravention of the conditions provided for in the agreement or any extension of their presence in such territory beyond the termination of the agreement;

(f) The action of a State in allowing its temtory, which it has placed at the disposal of another State, to be used by that other State for perpetrating an act of aggression against a third State;

(g) The sending by or on behalf of a State of armed bands, groups, irregulars or mercenaries, which carry out acts of armed force against another State of such gravity as to amount to the acts listed above, or its substantial involvement therein.

Article 4

The acts enumerated above are not exhaustive and the Security Council may determine that other acts constitute aggression under the provisions of the Charter.

Article 5

- No consideration of whatever nature, whether political, economic, military or otherwise, may serve as a justification for aggression.

- A war of aggression is a crime against international peace. Aggression gives rise to international responsibility.

- No territorial acquisition or special advantage resulting from aggression is or shall be recognized as lawful.

Article 6

Nothing in this Definition shall be construed as in any way enlarging or diminishing the scope of the Charter, including its provisions concerning cases in which the use of force is lawful.

Article 7

Nothing in this Definition, and in particular article 3, could in any way prejudice the right to self-determination, freedom and independence, as derived from the Charter, of peoples forcibly deprived of that right and referred to in the Declaration on Principles of International Law concerning Friendly Relations and Cooperation among States in accordance with the Charter of the United Nations, particularly peoples under colonial and racist regimes or other forms of alien domination: nor the right of these peoples to struggle to that end and to seek and receive support, in accordance with the principles of the Charter and in conformity with the above-mentioned Declaration.

Article 8

In their interpretation and application the above provisions are interrelated and each provision should be construed in the context of the other provisions.” (A/RES/29/3314 – Definition of Aggression, UN Documents).

Tomorrow: Australia’s involvement in Iraq (continued)

Dr. Venturino Giorgio Venturini – ‘George’ devoted some sixty years to study, practice, teach, write and administer law at different places in four continents. In 1975, invited by Attorney-General Lionel Keith Murphy, Q.C., he left a law chair in Chicago to join the Trade Practices Commission in Canberra – to serve the Whitlam Government. In time he witnessed the administration of a law of prohibition as a law of abuse, and documented it in Malpractice, antitrust as an Australian poshlost (Sydney 1980).

Dr. Venturino Giorgio Venturini – ‘George’ devoted some sixty years to study, practice, teach, write and administer law at different places in four continents. In 1975, invited by Attorney-General Lionel Keith Murphy, Q.C., he left a law chair in Chicago to join the Trade Practices Commission in Canberra – to serve the Whitlam Government. In time he witnessed the administration of a law of prohibition as a law of abuse, and documented it in Malpractice, antitrust as an Australian poshlost (Sydney 1980).

Like what we do at The AIMN?

You’ll like it even more knowing that your donation will help us to keep up the good fight.

Chuck in a few bucks and see just how far it goes!

Your contribution to help with the running costs of this site will be gratefully accepted.

You can donate through PayPal or credit card via the button below, or donate via bank transfer: BSB: 062500; A/c no: 10495969

3 comments

Login here Register here-

Jack Straw

-

Danny W

-

Michael Taylor

Return to home pageThe 3 Unwise Monkeys “Hear Evil” “See Evil” “Speak Evil”

Dr Venturini do you have an authoritative reference to support your assertions re John Howard to wit ‘Australian Prime Minister John Howard conspired with both reckless adventurers, purported ‘to advise’ both buccaneers, sent troops to Iraq before the war started, then lied to Parliament and to the Australian people. He continues to do so.’ ? Without an appropriate citation your opening premise carries no weight to support the main thrust of your argument.

Danny, if you read the series from the beginning, this will be answered for you. You notice, as you read, that Dr Venturini has used appropriate references or links.