Bush, Blair and Howard – Three reckless adventurers in Iraq (Part 31)

The Iraq Inquiry Report (2009-2016) documents how Tony Blair committed Great Britain to war early in 2002, lying to the United Nations, to Parliament, and to the British people, in order to follow George Bush, who had planned an aggression on Iraq well before September 2001.

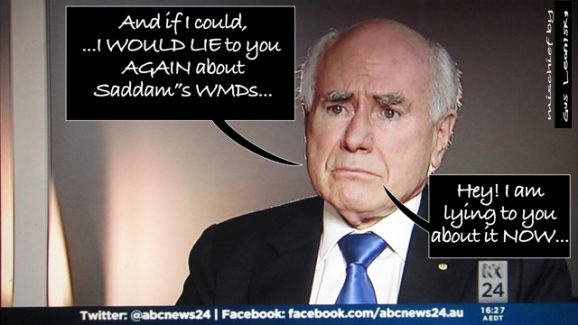

Australian Prime Minister John Howard conspired with both reckless adventurers, purported ‘to advise’ both buccaneers, sent troops to Iraq before the war started, then lied to Parliament and to the Australian people. He continues to do so.

Should he and his cabal be charged with war crimes? This, and more, is investigated by Dr George Venturini in this outstanding series.

Australia’s involvement in Iraq (continued)

In Australia, the government decided to lie about any Australian involvement, in full knowledge of the fact that a large bulk of Australian working people either supported the Bolsheviks, were interested in the socialist experiment or simply believed the Russians should be left alone to decide how to govern their own country.

As a member of the early Elope Force put it: “None of us had any heart for the Russian campaign … We had no right to be there. Had I known beforehand what the aim and nature of the mission was, I for one, would never have volunteered for the job.” [Emphasis added].

In those words is the summation of what passed for Anzackery, the cult of militarism.

Except for the second world war, Australia has been everywhere involved in battles which were no concern of it: from Sudan in 1885 to Vietnam in 1965 – and beyond. Every once in a while the practice of Anzackery is renewed: coffins are solemnly paraded, led by the usual chaplain (never mind what the faith of the dead soldier might have been!), the usual lone piper, and the drummer, with the usual ‘compromised’ flag (in the canton there is still the red saltire of Ireland!) – and all that in an atmosphere which is contrived solemnity because often the remains are those of soldiers killed in places such as the Thai-Malay border in 1964. How on earth did they get there?!

It is therefore unsurprising that the Iraq Inquiry was not greatly concerned with Australia – in part due to assumptions about it, in part to a habit of taking Australia’s participation for granted because always eagerly offered.

Thus, there is a reference in Section 1.1, paras. 316-338, pp.79-84 to the work of Mr. Richard Butler, the Australian diplomat and former Permanent Representative to the U.N. who succeeded Mr. Rolf Ekéus as the Executive Chairman of the United Nations Special Commission, UNSCOM, set up for an inspection regime to ensure Iraq’s compliance with policies concerning Iraqi production and use of weapons of mass destruction. (Review of Intelligence on Weapons of Mass Destruction [The Butler Report], 14 July 2004).

Section 3.2, which is on Development of U.K. strategy and options, January to April 2002 – “Axis of evil” to Crawford, is of tangential relevance only to the extent that it mentions Mr. Blair’s visit for the Commonwealth Heads of Government Meeting in Australia, during the course of which he “gave an interview to the Australian Broadcasting Corporation on 28 February. Blair stated that he agreed with President Bush “very strongly that weapons of mass destruction represent a real threat to world stability”; and that: “Those who are engaged in spreading weapons of mass destruction are engaged in an evil trade and it is important that we make sure that we have taken action in respect of it.” para. 187.

“On 3 March, Mr Blair was reported to have told Channel Nine in Australia: “We know [the Iraqis] are trying to accumulate … weapons of mass destruction, we know [Saddam Hussein] is prepared to use them. So this is a real issue but how we deal with it, that’s a matter we must discuss.” [Footnote omitted] para. 192.

Section 3.3 “addresses the development of UK policy on Iraq following Mr Blair’s meeting with President Bush at Crawford on 5 and 6 April 2002, at which Mr Blair proposed a partnership between the US and UK urgently to deal with the threat posed by Saddam Hussein’s regime, including Mr Blair’s Note to President Bush at the end of July proposing that the US and UK should use the UN to build a coalition for action.” [From the Introduction].

A 19 July 2002 Cabinet Office paper ‘Iraq: Conditions for Military Action’ noted that “an international coalition would be necessary to provide a military platform and would be desirable for political purposes. [Footnote omitted]. The “greater the international support, the greater the prospects of success”. Military forces would need agreement to use bases in the region. Without UN authorisation, there would be problems securing the support of NATO and EU partners, although Australia “would be likely to participate on the same basis as the UK”. France “might be prepared to take part if she saw military action as inevitable”. Russia and China might “set aside their misgivings if sufficient attention were paid to their legal and economic concerns”. [Emphasis added] para.263-265, at 47-48.

Section 3.4 “addresses the development of UK policy on Iraq and the UK’s discussions with the US between the end of July and President Bush’s speech to the UN General Assembly on 12 September 2002, in which he challenged the UN to act to address Iraq’s failure to meet the obligations imposed by the Security Council since Saddam Hussein’s invasion of Iraq in August 1990.”

There is part of that Section which deals with “the attitude of allies” (paras. 26-39), by which is meant France under the government of President Chirac. His opinion is given serious consideration because President Chirac resisted the use of military force (paras. 338-346), persisted in that view (paras. 443-455) and had his Foreign Minister Mr. Dominique de Villepin reiterate the lack of commitment to armed intervention. (paras. 554-560).

In this Section there is ample room for consideration of the position of Russia, China and Saudi Arabia, but one would look in vain for an appreciation of Australia’s view – nothing; Australia is not even an ally, it is given for granted that wherever Great Britain would go, it will follow.

Section 3.6 deals with the development of U.K. strategy on Iraq between the adoption of resolution 1441 on 8 November 2002 and Mr. Blair’s meeting with President Bush, in Washington, on 31 January 2003, as well as with other key developments in the U.K.’s thinking between mid-November and the end of January which had an impact on the strategy and the planning and preparation for military action.

The Section also deals with the Joint Intelligence Committee’s Assessments of Iraq’s declaration of 7 December 2002, and its view that there was a continuing policy of concealment and deception in relation to its chemical, biological, nuclear and ballistic missile programmes, which are addressed in Section 4.3; and how advice was sought from Lord Goldsmith, QC, the Attorney General, regarding the interpretation of U.N. Security Council Resolution 1441 (2002); the manner in which that advice was provided is considered in the whole of Section 5: 169 pages. The development of the options to deploy ground forces and the decision on 17 January to deploy a large scale land force for potential operations in southern Iraq rather than for operations in northern Iraq, as well as maritime and air forces, are dealt with in Sections 6.1 and 6.2. What planning the United Kingdom prepared for a post-Saddam Hussein Iraq is considered in Sections 6.4 and 6.5.

Section 3.6 records that between November 2002 and January 2003 Blair had started saying after conversation with Howard that it was best to gain a new U.N. Security Council Resolution. A second resolution would have made the process easier and the public support more certain. Communications from Dr. Blix that Iraq was reluctant to comply with the inspections assisted Blair’s position.

The Iraq Inquiry Report records that “Mr Blair and Mr John Howard, the Prime Minister of Australia, discussed the position on Iraq on 28 January. Mr Blair said that, militarily, it might “be preferable to proceed quickly”, but it “would be politically easier with a UN resolution”. He: “… intended to tell President Bush that the UN track was working. Blix had said … that Saddam was not co-operating. If he repeated this in reports on 14 February, and perhaps in early March there would be a strong pattern on non-co-operation and a good chance of a second resolution.” (Letter No.10 [junior official] to McDonald, 28 January 2003, ‘Prime Minister’s Telephone Conversation with John Howard).

Blair and Howard agreed that a second resolution would be “enormously helpful”. It would be better to try and fail than not to try at all for a second resolution but they should “pencil in a deadline beyond which, even without a second resolution, we should take a decision”. Mr Blair said that his instinct was that “in the end, France would come on board, as would Russia and China”. paras. 774-775.

Alastair John Campbell, a British journalist, broadcaster, political aide and author, best known for his work as Downing Street Press Secretary (1997–2000), followed by Director of Communications and Strategy (2000–2003), for Prime Minister Tony Blair, would write in praise of John Howard in A. Campbell and B. Hagerty, The Alastair Campbell diaries, volume 4: The burden of power: Countdown to Iraq, Hutchinson, London 2012.

As the Iraq Inquiry Report says: “In his diary for 29 January, Mr Campbell wrote: “For obvious reasons, Iraq was worrying [Tony Blair] more and more. He wasn’t sure Bush got just how difficult it was going to be without a second UNSCR, for the Americans as well as us. Everyone TB was speaking to, including tough guys like [John] Howard, was saying that they need a second resolution or they wouldn’t get support. TB felt that was the reality for him too, that he couldn’t deliver the party without it.” [Footnote omitted] para. 827

John Howard = tough guy, at least in the eyes of ‘people upstairs’, in London.

Section 3.7 is about development of the United Kingdom strategy and options during the period 31 January, when Blair met President Bush, and 7 March 2003.

During his meeting with President Bush, Prime Minister Blair sought American support for a further, ‘second’, Security Council resolution before military action was taken, and the meeting of the Security Council on 7 March, at which the U.K., U.S. and Spain tabled a revised draft resolution stating that Iraq would have failed to take the final opportunity offered by resolution 1441 unless the Council concluded on or before 17 March that Iraq was demonstrating “full, unconditional, immediate and active co-operation” with its obligations to disarm.

During that time, the U.K. Government was pursuing both intense diplomatic negotiations with the U.S. and other members of the Security Council about the way ahead on Iraq and a pro-active communications strategy about why Iraq had to be disarmed, if necessary by force, against the background of sharply divided opinion and constant political and public debate about the possibility of military action.

Continued Tuesday: Australia’s involvement in Iraq (continued)

Dr. Venturino Giorgio Venturini – ‘George’ devoted some sixty years to study, practice, teach, write and administer law at different places in four continents. In 1975, invited by Attorney-General Lionel Keith Murphy, Q.C., he left a law chair in Chicago to join the Trade Practices Commission in Canberra – to serve the Whitlam Government. In time he witnessed the administration of a law of prohibition as a law of abuse, and documented it in Malpractice, antitrust as an Australian poshlost (Sydney 1980).

Dr. Venturino Giorgio Venturini – ‘George’ devoted some sixty years to study, practice, teach, write and administer law at different places in four continents. In 1975, invited by Attorney-General Lionel Keith Murphy, Q.C., he left a law chair in Chicago to join the Trade Practices Commission in Canberra – to serve the Whitlam Government. In time he witnessed the administration of a law of prohibition as a law of abuse, and documented it in Malpractice, antitrust as an Australian poshlost (Sydney 1980).

Like what we do at The AIMN?

You’ll like it even more knowing that your donation will help us to keep up the good fight.

Chuck in a few bucks and see just how far it goes!

Your contribution to help with the running costs of this site will be gratefully accepted.

You can donate through PayPal or credit card via the button below, or donate via bank transfer: BSB: 062500; A/c no: 10495969

2 comments

Login here Register here-

wam

-

jim

Return to home pagejohn howard the schemer.

Mechanically (maniacally) driven by his middle name which was branded deep in his psyche by his ww1 father and made intransigent by a fierce belief in his righteousness.

To my mind the most tragic incident in my 8 decades was a @@^@@&& birthday cake.

It is wrong to say I enjoyed these posts but I am so glad I am reading them.

It may be a forlorn hope but I may live long enough to see the little prick shamed.

I’ll bet this will pan out just like when Joe Bjelkii (QLD premier) was found guilty of corruption after his state funeral of course you bet you is.